15 Woolly Mammoth Facts You Should Know

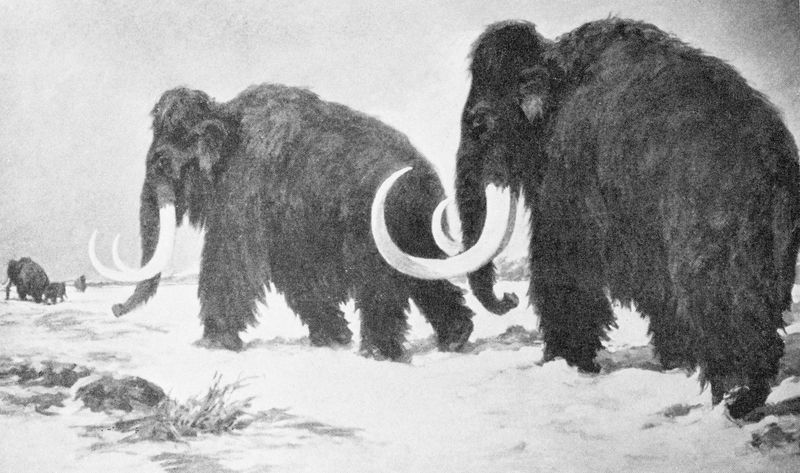

The woolly mammoth, an iconic Ice Age giant, roamed Earth until surprisingly recent times. These massive, fur-covered relatives of modern elephants have captured our imagination through cave paintings, frozen specimens, and countless museum displays.

Whether you’re a paleontology enthusiast or simply curious about prehistoric life, these fascinating facts about woolly mammoths will transport you back to a world where these magnificent creatures dominated the landscape.

1. Not Dinosaurs

Woolly mammoths lived during the Pleistocene epoch, long after dinosaurs went extinct. While dinosaurs disappeared about 65 million years ago, mammoths only emerged around 5 million years ago.

Many people mistakenly group these shaggy elephants with dinosaurs, but they’re actually mammals that shared the planet with early humans. This timeline makes them practically modern compared to T. rex!

2. Hairy Insulation System

Mammoths sported an incredible double-coat system that put our winter jackets to shame. Their outer layer consisted of guard hairs up to 3 feet long, while underneath lay a dense woolly undercoat.

This natural insulation trapped air to create exceptional warmth. Scientists believe their fur ranged from reddish-brown to darker shades, not unlike the color variations we see in modern elephants’ skin tones.

3. Curved Tusks Could Reach 15 Feet

Unlike today’s elephants with relatively straight tusks, mammoths developed spectacular curved tusks that could grow up to 15 feet long! These impressive structures grew throughout their lifetime.

The tusks served multiple purposes: digging through snow to find vegetation, defending against predators, and attracting mates. Scientists can even read mammoth tusks like tree rings to determine age and health conditions.

4. They Had Tiny Ears

Modern African elephants sport large, flapping ears that release body heat. Mammoths evolved the opposite adaptation with tiny ears tucked close to their heads to prevent heat loss in frigid environments.

This ear adaptation, combined with their thick fur and a small surface-to-volume ratio, helped these giants maintain crucial body heat. Their compact ears measured just about one-tenth the size of their African elephant cousins.

5. Mammoth Poop Reveals Their Diet

Preserved mammoth dung has given scientists an exact menu of what these giants ate. Their diet consisted primarily of grasses, sedges, flowers, shrubs, and mosses from the mammoth steppe ecosystem.

Adult mammoths consumed an astonishing 300-700 pounds of vegetation daily. Researchers have even found undigested plant material in frozen specimens, providing a direct window into their last meals and helping reconstruct ancient environments.

6. Mammoths Had Built-in Antifreeze

Blood samples from frozen mammoths revealed special cold-adaptive genetic mutations. Their blood contained a hemoglobin variant that could deliver oxygen efficiently even at very low temperatures.

Additionally, their bodies produced unique proteins that prevented cell damage during freezing. This biological antifreeze, combined with their physical adaptations, allowed mammoths to thrive in temperatures as low as -40°F, where most large mammals would struggle to survive.

7. Last Mammoths Survived Until 4,000 Years Ago

While most mammoth populations disappeared around 10,000 years ago as the Ice Age ended, a surprising pocket of survivors held out on Wrangel Island off Siberia until just 4,000 years ago.

This means mammoths were still roaming this remote Arctic island while Egyptians were building the pyramids! These final mammoths were smaller than their ancestors, an example of island dwarfism resulting from limited resources.

8. Baby Mammoths Drank Milk For Eight Years

Mammoth calves relied on their mothers’ milk much longer than modern elephant calves. Chemical analysis of mammoth teeth shows they nursed for up to eight years before fully transitioning to solid foods.

This extended nursing period likely helped young mammoths build up fat reserves necessary for surviving harsh winters. The lengthy dependency also suggests mammoths had complex social structures and strong maternal bonds, similar to modern elephant families.

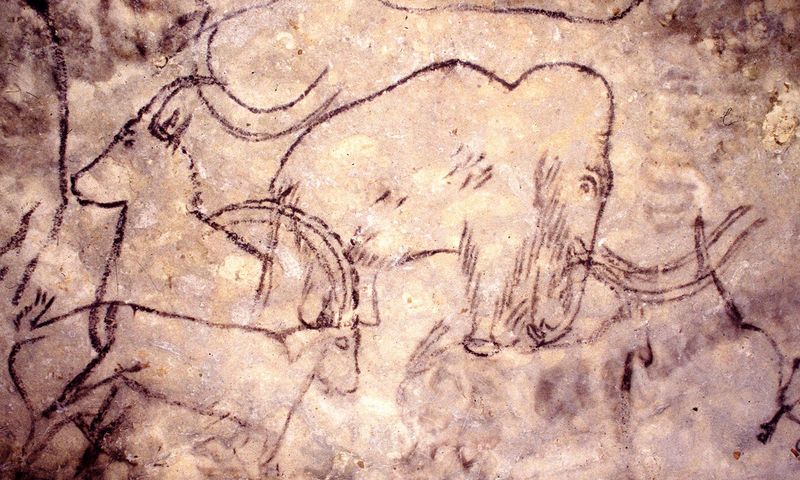

9. Humans Hunted And Revered Them

Our ancestors both hunted mammoths and honored them in art. Cave paintings across Europe depict mammoth hunts, while ancient people created figurines carved from mammoth ivory and bone.

Archaeological sites have revealed mammoth bone houses where early humans used their massive skeletons as building materials. Some indigenous cultures passed down stories about these giant beasts, creating a cultural memory that outlived the species itself.

10. Perfectly Preserved Specimens

Several complete mammoth carcasses have been found frozen in permafrost, some so well-preserved that their flesh remained pink and scientists could extract liquid blood. The most famous specimen, baby Lyuba, still had milk in her stomach.

These frozen time capsules provide unprecedented insights into mammoth anatomy. Some specimens even retained their stomach contents, skin, hair, and internal organs, allowing scientists to study prehistoric tissue samples directly.

11. Trunk Had 40,000 Muscles

A mammoth’s trunk contained approximately 40,000 muscles, making it extraordinarily dexterous. This versatile appendage could pluck tiny flowers or uproot entire trees with equal precision.

The trunk’s tip featured finger-like projections that could grasp small objects. Beyond gathering food, mammoths used their trunks to throw snow on their backs for additional insulation during blizzards and to siphon water for drinking and bathing.

12. Mammoth Teeth Weighed 8 Pounds Each

Mammoth molars were grinding powerhouses, weighing up to 8 pounds each and measuring nearly a foot long. Unlike our permanent teeth, mammoths replaced their molars six times throughout their lives.

As one set wore down from grinding tough vegetation, another would slowly push forward from the back of the jaw. The distinctive ridged pattern of their teeth created efficient grinding surfaces perfectly adapted for processing the fibrous plants of the Ice Age steppe.

13. Scientists Want To Resurrect Them

Several research teams are working to bring mammoths back through genetic engineering. By splicing preserved mammoth DNA into elephant genomes, scientists hope to create mammoth-elephant hybrids with cold-weather adaptations.

This de-extinction project aims to introduce these engineered mammoths to the Siberian tundra. Proponents argue these creatures could help restore grassland ecosystems and potentially slow permafrost melting by trampling snow and exposing the ground to colder air.

14. Mammoths Trumpeted Like Elephants

Based on throat anatomy studies, scientists believe mammoths produced sounds similar to modern elephant calls. Their vocal abilities likely included low-frequency rumbles that could travel miles across the tundra.

These sounds were crucial for locating family members during blizzards or communicating across vast territories. Mammoth herds probably maintained complex vocal traditions passed between generations, with unique calls identifying different family groups.

15. They Migrated Vast Distances

Chemical analysis of mammoth tusks reveals these giants undertook enormous seasonal migrations. By studying isotope patterns that vary by region, scientists can track lifetime movement patterns preserved in tusk layers.

One Alaskan mammoth nicknamed Woolly traveled an estimated 50,000 miles during its 28-year life, equivalent to circling Earth twice! These migrations followed food availability as seasons changed, with herds likely following traditional routes passed down through generations.