Why Some Sharks Are Venturing Into American Rivers (And What Keeps Others In The Ocean Depths)

Sharks are showing up in unexpected places lately – including American rivers! These ancient predators have mostly stuck to oceans throughout history, but some species are now swimming upstream into freshwater.

This surprising behavior has scientists scrambling to understand what’s driving these oceanic visitors inland while their deep-sea cousins remain firmly committed to saltwater living.

Let’s explore what’s causing this fascinating shift in shark behavior.

1. Why Are Some Sharks Venturing Into American Rivers?

Climate change plays a major role in this unusual migration pattern. Rising ocean temperatures are pushing certain shark species to seek more comfortable waters, sometimes leading them into cooler river systems.

Food availability is another powerful motivator. As fish populations shift due to changing environmental conditions, sharks follow their prey wherever they go – even upstream.

Human activities like overfishing coastal areas may inadvertently be forcing sharks to explore new hunting grounds.

Some shark species naturally possess special adaptations that allow them to regulate salt levels in their bodies, making river exploration possible.

These physiological superpowers give certain sharks the unique ability to thrive in both salt and freshwater environments.

2. Bull Shark

The ultimate river explorer, bull sharks can regulate salt in their bodies better than almost any other shark species.

This remarkable ability allows them to swim thousands of miles up rivers like the Mississippi, Amazon, and even Australia’s Brisbane River.

Female bulls often use rivers as nurseries, giving birth in freshwater where fewer predators threaten their pups.

These stocky, aggressive sharks reach lengths of 7-11 feet and have been spotted as far north as Illinois in the Mississippi River system.

Their adaptability makes them particularly concerning to researchers, as climate change may drive more bulls into populated waterways where humans swim and boat regularly.

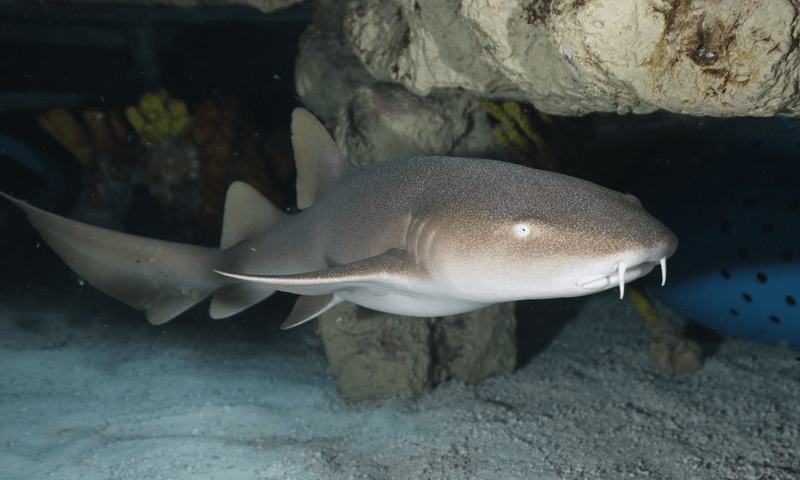

3. Nurse Shark

Nurse sharks, typically found in shallow coastal waters, have occasionally been spotted venturing into river systems, particularly in brackish estuaries.

While they primarily reside in warm, tropical waters, their adaptability to varying salinities allows them to move into river mouths, especially when food sources are abundant.

These sharks are known for their slow-moving, bottom-dwelling nature, making them less likely to venture far into deeper rivers but still capable of navigating brackish waters near shorelines.

Their presence in these environments suggests a level of flexibility in their habitat choices, allowing them to thrive in both coastal and freshwater-adjacent areas.

4. Lemon Shark

Named for their yellowish skin tone, lemon sharks occasionally venture into river mouths and estuaries during warm months.

They’re particularly fond of mangrove areas where freshwater meets salt, creating brackish zones rich in smaller fish.

Young lemons use these areas as nurseries, staying in shallow, protected waters until they’re large enough to brave the open ocean. Unlike bulls, they rarely swim far upstream, preferring to stay where they can retreat to saltier conditions.

Scientists have documented them in Florida’s Indian River Lagoon system and similar coastal waterways along the southeastern United States, where their presence indicates healthy transitional ecosystems.

5. Sandbar Shark

Sandbar sharks are coastal wanderers that occasionally swim into the lower portions of river systems, especially during summer.

With their tall dorsal fins and medium-sized bodies (typically 6-8 feet), they’re often mistaken for more dangerous species, creating unwarranted fear.

These sharks prefer the sandy bottoms of bays and harbors but will follow prey fish into freshwater. Chesapeake Bay and its tributary rivers serve as crucial nursery grounds for sandbar sharks, where females give birth to live young.

Commercial fishing has severely reduced their numbers, making their river appearances increasingly rare – a glimpse of these sharks is now considered a special event for wildlife enthusiasts.

6. Blacktip Shark

Famous for their spectacular feeding frenzies where they leap from the water, blacktip sharks occasionally venture into river mouths during their coastal migrations. The distinctive black markings on their fin tips make them easily identifiable even in murky river waters.

They’re highly sensitive to salinity changes and typically stay in the mixing zones where rivers meet oceans.

Young blacktips use these estuarine environments as protective nurseries, hiding among mangroves and seagrass beds.

Fishermen along the Gulf Coast sometimes spot blacktips in the lower Mississippi and Mobile Bay delta systems, especially during spring and fall migrations when water temperatures are transitioning.

7. Shortfin Mako Shark

The speedsters of the shark world, shortfin makos rarely enter rivers but have been documented in the lower Hudson and Delaware Rivers during unusual warming events.

These sleek, torpedo-shaped sharks can swim at incredible speeds exceeding 45 mph, making them the fastest sharks in the ocean.

Their highly specialized bodies are built for open-ocean hunting, not the confined spaces of rivers. When they do appear in river systems, it’s typically a lost individual or one following a large school of prey fish.

Marine biologists consider river sightings of makos to be warning signs of disrupted ocean ecosystems, as these pelagic predators normally avoid shallow, brackish waters entirely.

8. Great White Shark

The ocean’s most famous predator rarely ventures into freshwater, but there have been verified reports of great whites entering the lower reaches of major rivers like the Mississippi.

These massive sharks cannot regulate their salt balance in freshwater and would die if trapped upstream.

Great whites occasionally chase prey into river mouths during feeding events, creating brief but dramatic appearances.

Their bodies, evolved for cold, open-ocean hunting, quickly become stressed in the warmer, less saline river environments.

A great white spotted in a river is usually a young individual that has made a navigational error – they typically retreat to saltwater within hours, following their finely-tuned internal compass.

9. Tiger Shark

Known as the “garbage cans of the sea” for eating almost anything, tiger sharks occasionally swim into the lower portions of river systems in tropical regions.

Their distinctive tiger-stripe pattern fades as they mature but remains visible in younger individuals that are more likely to explore rivers.

These sharks have remarkable homing abilities but sometimes follow prey into unfamiliar territories. In Florida and the Gulf states, tiger sharks have been documented in river mouths and bays during particularly warm seasons.

Unlike bull sharks, tigers cannot survive long in pure freshwater – their kidney function depends on certain salt levels, limiting how far upstream they can safely venture.

10. Hammerhead Shark

The unmistakable hammer-shaped head makes these sharks instant celebrities when they rare appear in coastal rivers.

Smaller hammerhead species, particularly scalloped and bonnethead varieties, occasionally venture into river mouths and estuaries during seasonal migrations.

Their unique head shape, which spreads their electrical sensors wide apart, works as an advantage in the murky conditions of river mouths.

Hammerheads have been spotted in Florida’s St. Johns River and similar systems along the southeast coast.

These sightings typically occur during unusually warm periods or when coastal prey populations have shifted, forcing the sharks to explore new hunting grounds.

11. Why Do Other Sharks Prefer The Ocean Depths?

Evolutionary specialization has created sharks perfectly adapted to deep-ocean environments that simply cannot function in shallow rivers. Their bodies depend on specific pressure, temperature, and salinity levels found only in the ocean depths.

Many deep-sea sharks have specialized sensory systems tuned to detect prey in the darkness of the abyss. These sensitive organs would be overwhelmed by the noisy, sediment-filled river environments.

Food sources also keep deep-dwellers in the ocean – they’ve evolved to hunt specific prey like squid, deep-sea fish, and marine mammals that aren’t available in freshwater systems. These specialized hunters would starve in rivers, even if they could physically tolerate the conditions.

12. Goblin Shark

With a face only a mother could love, the prehistoric-looking goblin shark lives at depths between 890-3,150 feet where immense pressure and near-freezing temperatures create an alien world.

Their bizarre extendable jaws – which can project forward to catch prey – would be useless in shallow river currents.

Goblin sharks have soft, flabby bodies adapted to the crushing pressures of the deep sea. Bringing one to the surface causes severe tissue damage, similar to what would happen if they attempted to enter a river system.

Their pale pink bodies lack the melanin protection needed for sunlit waters, as they evolved in an environment where sunlight never penetrates.

13. Sixgill Shark

Ancient and mysterious, sixgill sharks represent a living link to prehistoric times. Most modern sharks have five gill slits, but sixgills retain the primitive six-gill arrangement of their ancestors from over 200 million years ago.

These sharks inhabit depths between 700-8,200 feet, where high pressure and stable conditions have remained unchanged for millions of years.

Their large, green eyes contain reflective layers that amplify the faintest light in their dark domain – adaptations that would be disadvantageous in bright, variable river environments.

Sixgills move slowly to conserve energy in their food-scarce habitat, a strategy that would make them vulnerable to swift river currents.

14. Megamouth Shark

Only discovered in 1976, the megamouth shark represents how little we know about deep-ocean species. These filter-feeders have enormous mouths lined with luminescent tissue that glows faintly, attracting plankton which they then filter through their specialized gill rakers.

Megamouths vertically migrate each day, following plankton from depths of 15,000 feet during daylight to around 500 feet at night. Their feeding strategy depends entirely on oceanic plankton blooms that don’t exist in rivers.

With fewer than 100 specimens ever documented by science, megamouths epitomize the mysterious nature of deep-sea sharks that remain firmly committed to ocean habitats.

15. Deepwater Catshark

Small but specialized, deepwater catsharks have evolved remarkable adaptations for life in the eternal darkness of the ocean abyss.

Many species have developed bioluminescence – they literally glow in the dark – to communicate with potential mates and confuse predators.

Their bodies contain high levels of urea and trimethylamine oxide (TMAO) to maintain cell volume against the crushing pressure of depths exceeding 8,200 feet. These chemical adaptations would fail catastrophically in freshwater, causing their cells to rupture.

Catsharks lay distinctive egg cases called “mermaid’s purses” that are specifically designed to develop in stable, high-pressure environments – conditions impossible to replicate in variable river systems.