What Makes The Discovery Of The Rare ‘Thunder Bird’ Skull So Significant?

Scientists recently unearthed a remarkably preserved skull of Genyornis newtoni, nicknamed the ‘Thunder Bird,’ causing excitement throughout the paleontological world.

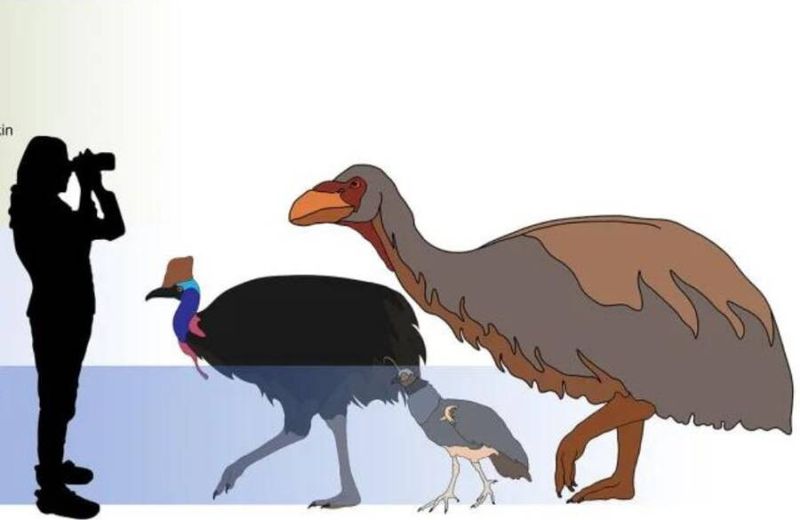

This massive flightless bird, which stood over 6 feet tall and weighed around 500 pounds, roamed Australia until its extinction about 50,000 years ago.

The skull discovery provides unprecedented insights into prehistoric megafauna and might finally solve long-standing mysteries about these ancient creatures and their sudden disappearance.

1. Revolutionary Dating Techniques Confirm Age

The Thunder Bird skull underwent groundbreaking carbon dating analysis that pinpointed its age with remarkable precision. Scientists applied multiple methods simultaneously, including amino acid racemization and electron spin resonance dating.

These techniques confirmed the specimen lived approximately 50,000 years ago – right around the time these magnificent creatures vanished from Australia. The dating accuracy helps establish a clearer timeline of when these birds existed alongside early humans.

For researchers, this precision creates a crucial reference point to understand extinction patterns of Australian megafauna during a period of significant climate change and human arrival.

2. Human Interaction Evidence

Tiny but unmistakable cut marks on the Thunder Bird skull tell a dramatic story of human-bird encounters. These marks match stone tool patterns from the same time period, suggesting humans hunted these massive birds.

More fascinating still, the skull shows signs of ceremonial handling – specific areas were rubbed smooth, possibly from ritual use after the bird’s death. This gives us a rare glimpse into early human cultural practices in ancient Australia.

The location of the cut marks indicates humans knew exactly how to efficiently process these birds, suggesting regular hunting rather than opportunistic scavenging.

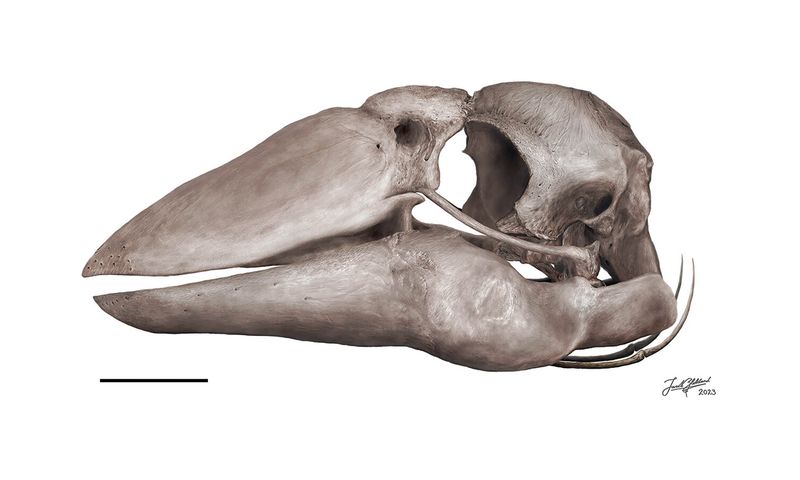

3. Complete Cranial Structure Preserved

Unlike previous fragmentary remains, this Thunder Bird skull retains almost 90% of its original structure. The beak, eye sockets, and delicate brain case survived intact after tens of thousands of years underground.

Paleontologists can now study the bird’s sensory abilities, particularly its vision and smell capacities. The skull’s exceptional preservation even shows minute details of blood vessel pathways and nerve channels.

Most exciting for researchers is the intact auditory region, suggesting these birds had sophisticated hearing – possibly used for long-distance communication across Australia’s ancient plains or detecting approaching predators.

4. Diet Mysteries Finally Solved

Microscopic plant particles embedded in the Thunder Bird’s beak crevices reveal its last meals! Scientists identified seeds, fibrous plants, and surprisingly, fruit remnants that survived millennia.

The bird’s powerful jaw structure, now fully visible, shows adaptations for both tough vegetation and softer foods. This contradicts earlier theories that Genyornis ate only hard seeds and nuts.

The skull’s wear patterns suggest these birds were versatile omnivores that could switch diets seasonally. This adaptability makes their eventual extinction even more puzzling, as flexible eaters typically survive environmental changes better than dietary specialists.

5. Genetic Material Extraordinarily Preserved

Against all odds, traces of ancient DNA survived within the Thunder Bird skull’s dense bone structure. Protected from degradation by unique mineral conditions at the discovery site, these genetic fragments offer unprecedented research opportunities.

Scientists have already extracted enough material to begin mapping the Thunder Bird’s genetic relationship to modern birds. Early results suggest surprising connections to today’s emus and cassowaries.

The genetic material might also reveal adaptation patterns that helped these birds survive in Australia’s changing prehistoric environment, including drought resistance mechanisms that modern conservation efforts could learn from.

6. Geographic Range Expansion Theories

Found in an area previously thought uninhabited by Thunder Birds, this skull dramatically expands their known territory. The discovery location suggests these massive birds roamed across much more of ancient Australia than scientists believed.

Geological analysis of soil embedded in the skull’s cavities contains minerals specific to regions hundreds of miles away. This indicates either seasonal migration patterns or a much larger habitat range for these supposedly sedentary birds.

Climate reconstruction based on the discovery site suggests Thunder Birds adapted to more varied environments than previously thought, from coastal plains to semi-arid interiors, showing remarkable ecological flexibility.

7. Extinction Timeline Recalibration

The Thunder Bird skull has forced scientists to redraw extinction timelines for Australian megafauna. Previously, researchers believed these birds vanished abruptly around 45,000 years ago.

New evidence from this specimen pushes that date closer to 50,000 years ago, aligning more precisely with human arrival patterns on the continent. The skull shows signs of environmental stress – abnormal bone growth patterns indicating nutritional deficiencies before death.

This suggests a more gradual decline rather than sudden disappearance, potentially caused by a combination of climate shifts and human hunting pressure rather than a single catastrophic event.

8. Size Estimation Breakthrough

The massive skull provides definitive evidence that Thunder Birds grew substantially larger than previously estimated. Based on skull-to-body ratios from related species, scientists now calculate these birds stood over 7 feet tall – nearly a foot taller than earlier estimates!

Weight calculations have also been revised upward to approximately 600 pounds, making them among the heaviest birds ever to exist. The skull’s attachment points for neck muscles suggest tremendous strength, likely used for powerful pecking motions.

These size revisions help explain fossil footprints once thought too large to belong to Thunder Birds, solving a long-standing paleontological puzzle.

9. Predator-Prey Relationship Indicators

Healed puncture wounds on the Thunder Bird skull tell a surprising survival story! The marks match the teeth spacing of Thylacoleo carnifex – the marsupial lion – Australia’s apex predator of the time.

Even more astonishing, the bird clearly survived this attack, as bone regrowth shows the wounds had healed. This suggests Thunder Birds were tough enough to fend off predators or fast enough to escape after initial contact.

The location of these marks on the skull’s rear portion indicates ambush hunting techniques by predators, giving us unprecedented insights into prehistoric hunting behaviors and ecological relationships in ancient Australia.

10. Cultural Significance To Indigenous Australians

The Thunder Bird skull discovery aligns remarkably with Aboriginal oral histories that describe enormous birds called “Mihirung Paringmal.” These stories, passed down for countless generations, accurately describe birds matching Genyornis in appearance and behavior.

Indigenous knowledge keepers have identified specific narrative elements that match anatomical features only visible in this newly discovered complete skull. The discovery site itself was predicted by Aboriginal elders based on traditional knowledge of animal habitats.

This convergence of scientific discovery and indigenous knowledge represents a powerful validation of traditional ecological understanding that spans tens of thousands of years.

11. Climate Adaptation Clues

Microscopic analysis of the Thunder Bird skull reveals unexpected growth rings similar to tree rings! These bone growth patterns record seasonal changes and environmental stresses throughout the bird’s life.

Scientists can now track decade-by-decade climate variations in prehistoric Australia by studying these growth patterns. The skull shows evidence of surviving several severe drought periods, indicating remarkable resilience.

Most fascinating are structural adaptations in the nasal cavity that appear designed for water conservation – specialized turbinate bones that reduce moisture loss during breathing. This adaptation might explain how Thunder Birds survived in increasingly arid conditions before their ultimate extinction.