6 Whales That Continue To Be Hunted Today In Spite Of Conservation Efforts

When we think of whales, we picture magnificent creatures gliding through ocean depths, their massive bodies a testament to nature’s wonder.

Yet despite global conservation efforts, several whale species still face hunting threats today. The balance between cultural traditions, economic interests, and wildlife protection creates a complex challenge for these marine giants.

Let’s explore which whales remain targets and what this means for their future.

1. Minke Whales – The Most Frequently Hunted

Minke whales have become the primary target for countries that still permit whaling. These smaller baleen whales grow to about 35 feet long and are found in oceans worldwide. Their relatively abundant numbers make them the focus of commercial hunts, especially in the North Atlantic and Antarctic waters.

Japan, Norway, and Iceland regularly hunt minkes under various pretexts, from scientific research to cultural tradition. Approximately 600-800 minkes are killed annually despite international criticism. The meat appears in markets and restaurants, though demand has declined in recent decades.

2. Fin Whales – Second Largest, Still Targeted

Reaching lengths of 85 feet, fin whales are magnificent ocean giants second only to blue whales in size. Their streamlined bodies can propel them at speeds up to 23 mph, earning them the nickname “greyhounds of the sea.” Yet this speed hasn’t saved them from hunters.

Iceland’s whaling industry occasionally targets fins, with meat exported to Japan or sold to tourists as exotic cuisine. The species remains vulnerable with approximately 100,000 individuals left worldwide. Each fin whale yields massive profits – up to $200,000 worth of meat and products from a single animal.

3. Sei Whales – Mysterious And Vulnerable

Sei whales remain among the least understood of the large whales. They’re sleek, fast swimmers that can reach 64 feet in length with a bluish-gray coloration that fades to white underneath. Their mysterious nature hasn’t protected them from harpoons.

Commercial whalers began targeting seis after other whale populations declined. Their meat and oil fetch high prices in specialized markets. The global population hovers around 80,000 individuals – a fraction of historical numbers.

Recovery efforts face challenges because sei whales typically live far offshore, making research and protection difficult. Their preference for deep ocean habitats keeps them hidden from most observers.

4. Bryde’s Whales – Tropical Targets

Named after Norwegian consul Johan Bryde, these tropical whales have distinctive ridges running along their heads. Smaller than some baleen whales at 40-55 feet long, they’re year-round residents of warm waters between 40°N and 40°S latitude.

Their tropical habitat makes them accessible targets for whalers in regions where other species migrate seasonally. Japan has historically hunted Bryde’s whales under scientific permits, though critics question the genuine scientific value.

Identification challenges complicate conservation efforts – Bryde’s whales are easily confused with sei whales and Eden’s whales. This taxonomic uncertainty makes population assessments difficult, with estimates ranging from 90,000-100,000 worldwide.

5. Sperm Whales – Hunted For Their Unique Properties

With their massive square-shaped heads and wrinkled skin, sperm whales stand out among cetaceans. Males can reach 60 feet long and weigh up to 45 tons. Their distinctive appearance comes from the spermaceti organ in their heads – a waxy substance historically prized for candles, cosmetics, and machine lubricants.

Though large-scale commercial hunting ended decades ago, limited takes still occur. The spermaceti and ambergris (a substance formed in their digestive systems) remain valuable, with ambergris fetching thousands of dollars per pound for perfume production.

These deep-diving champions can plunge 7,000 feet below the surface hunting giant squid. Their complex social structures and communications suggest high intelligence, adding ethical concerns to their continued hunting.

6. Bowhead Whales – Arctic Giants Under Pressure

Bowheads are the ice whales of the Arctic, with massive heads comprising one-third of their 60-foot bodies. Their 17-inch thick blubber layer – the thickest of any animal – helps them survive frigid polar waters. These remarkable creatures can live over 200 years, making them the longest-lived mammals on Earth.

Indigenous communities in Alaska, Russia, and Canada maintain limited subsistence hunts of bowheads. The International Whaling Commission allows these traditional harvests that provide food and cultural continuity for Arctic peoples.

Unlike commercial whaling, these subsistence hunts follow strict quotas designed to maintain sustainable populations. Around 50 bowheads are taken annually from a population that has rebounded to roughly 25,000 individuals.

7. The Economic Reality Behind Modern Whaling

Modern whaling persists largely due to economic incentives rather than necessity. A single large whale can yield meat and products worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Government subsidies often keep whaling operations profitable despite declining consumer demand.

Japan’s whaling industry receives approximately $50 million annually in government support. Without these subsidies, commercial whaling would likely collapse under its own financial weight. Whale watching generates far more revenue globally – over $2 billion annually compared to roughly $31 million for whale products.

The economic argument for conservation grows stronger each year. A living whale contributes to ocean health and generates sustainable tourism income for decades, while a hunted whale provides a one-time profit.

8. Legal Loopholes In International Protection

The 1986 International Whaling Commission moratorium should have ended commercial whaling. Instead, hunting continues through three major loopholes. Countries can issue “scientific research” permits, file official objections to the moratorium, or claim indigenous subsistence needs.

Japan exploited the scientific research exception for decades before withdrawing from the IWC in 2019 to resume commercial whaling in their waters. Norway and Iceland simply filed objections to the moratorium, exempting themselves from its restrictions.

These legal maneuvers highlight the weakness of international conservation agreements that lack enforcement mechanisms. Without universal participation and compliance, even well-intentioned regulations can be circumvented, leaving whales vulnerable despite apparent protections.

9. Cultural Traditions Vs. Conservation Ethics

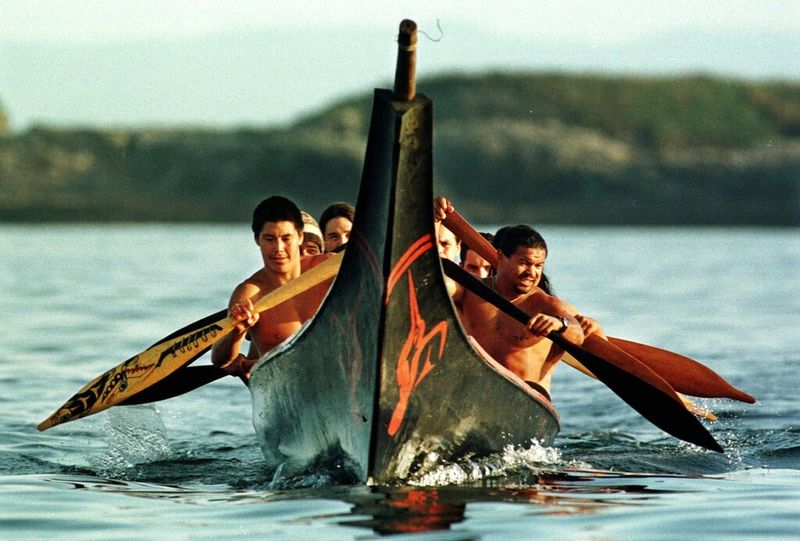

Some communities have hunted whales for centuries, weaving the practice into their cultural identity. In places like the Faroe Islands, the “grindadráp” hunt of pilot whales dates back over 1,000 years and remains a community ritual that distributes meat freely among locals.

Indigenous peoples in Alaska and Siberia depend on bowhead whales not just for food but for spiritual and cultural continuity. These traditional hunts raise complex questions about balancing cultural preservation with modern conservation ethics.

Finding middle ground requires acknowledging both the importance of cultural heritage and the reality of changing ecological awareness. Sustainable quotas, humane hunting methods, and respect for the animals hunted represent potential compromises that honor both tradition and conservation.

10. How We Can Help Protect Whales

Making whale-friendly consumer choices creates market pressure against whaling. Avoid products containing whale derivatives and research the policies of companies you support. When traveling, choose ethical whale watching operators that maintain proper distances and limit viewing time.

Support organizations dedicated to marine conservation through donations or volunteer work. Groups like Sea Shepherd, Whale and Dolphin Conservation, and Oceana actively monitor illegal whaling and advocate for stronger protections.

Your voice matters too! Contact elected officials to support marine protected areas and stronger international agreements. Share accurate information about whaling on social media to raise awareness. Even small actions, when multiplied across millions of concerned citizens, create powerful momentum for change.

11. The Future Of Whales In Our Changing Oceans

Climate change presents perhaps the greatest long-term threat to whale populations. Rising ocean temperatures disrupt food chains, while acidification damages the ecosystem that supports their prey. Whales that evolved to feed in specific regions now face unpredictable food availability as krill and fish populations shift.

Increasing ship traffic brings deadly collision risks and noise pollution that interferes with whale communication. Entanglement in fishing gear claims thousands of cetacean lives annually.

Yet there’s reason for hope. Technological solutions like ropeless fishing gear and acoustic warning systems are being developed. Marine protected areas are expanding globally. If we address both direct hunting and these broader environmental challenges, whales may yet recover to fill their crucial role in healthy ocean ecosystems.