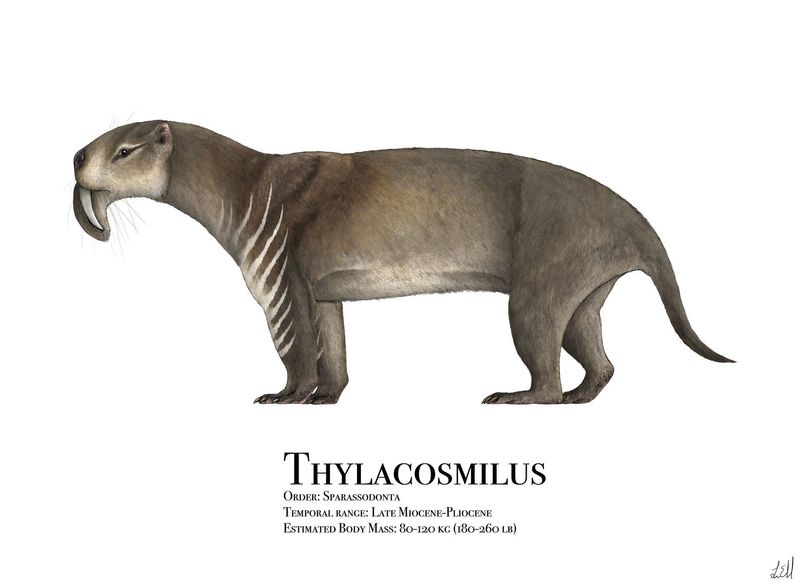

Thylacosmilus: Nature’s Strangest Predator With Saber Fangs And A Pouch

Imagine a bizarre creature that combines the deadly fangs of a saber-toothed cat with the pouch of a kangaroo! Meet Thylacosmilus, an extinct predator that roamed South America millions of years ago.

This fascinating animal represents one of evolution’s most remarkable experiments – a marsupial that independently evolved saber teeth similar to the more famous Smilodon, but with its own unique twist.

Let’s explore the weird and wonderful world of this ancient beast that continues to puzzle scientists today.

1. First Discovered In 1934

The first Thylacosmilus fossils were unearthed in Argentina in 1934 by paleontologist Elmer Riggs during an expedition from Chicago’s Field Museum. When scientists first examined these strange remains, they were astounded by what they’d found – a marsupial with saber teeth!

The name Thylacosmilus means “pouch knife” in Greek, perfectly describing its most distinctive features. The initial discovery included a well-preserved skull that clearly showed both the saber teeth and the marsupial characteristics.

For decades, only a few specimens were known, making this creature one of paleontology’s rarest treasures. Each new discovery helps scientists better understand this evolutionary marvel.

2. Not Actually A Cat

Despite its cat-like appearance, Thylacosmilus wasn’t related to cats at all! This creature belonged to the marsupial family – the same group as kangaroos, koalas, and opossums. While saber-toothed cats like Smilodon were placental mammals (related to modern lions and tigers), Thylacosmilus evolved its similar features completely independently.

Scientists call this ‘convergent evolution’ – when unrelated animals develop similar traits because they face similar environmental challenges. This prehistoric marvel lived in South America from 9 to 3 million years ago during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs.

3. Even Bigger Fangs Than Smilodon

Thylacosmilus took the saber-tooth concept to the extreme. Its upper canines were proportionally longer than those of Smilodon, extending beyond the lower jaw even when the mouth was closed! These impressive daggers continued growing throughout the animal’s life, unlike the teeth of modern mammals.

To protect these precious weapons, Thylacosmilus evolved specialized sheaths on its lower jaw where the sabers could rest safely. Imagine walking around with two massive knives constantly hanging from your mouth – that’s essentially what this creature did! These dental daggers likely reached up to 7 inches in length.

4. Bone-Crushing Bite Force

While those impressive fangs get all the attention, Thylacosmilus had another surprising adaptation – an incredibly powerful bite force. Recent studies of its skull suggest it could apply tremendous pressure with its jaws, possibly even stronger than modern-day lions or tigers.

The creature’s skull was reinforced with extra bone to handle these stresses. Unlike Smilodon, which had relatively weak jaws designed mainly for slashing, Thylacosmilus may have used its bite to crush bones and tear through tough hides.

This combination of slicing sabers and crushing power made it a truly formidable predator in the ancient South American ecosystem.

5. Pouched Predator

As a marsupial, Thylacosmilus females carried their young in a pouch, just like modern kangaroos and koalas. This makes it one of the few known predatory pouched mammals in history! Baby Thylacosmilus would have been born tiny and undeveloped, then crawled into the mother’s pouch to continue growing.

Imagine a fierce predator with deadly sabers also nurturing tiny, helpless babies in her pouch! This reproductive strategy differs dramatically from placental predators like lions or wolves, whose young develop more fully before birth.

This unique combination of deadly predator and pouched parent makes Thylacosmilus truly one of nature’s most fascinating evolutionary experiments.

6. Built Like A Bear, Not A Cat

Despite often being compared to saber-toothed cats, Thylacosmilus actually had a body more similar to a bear! It featured short, powerfully built limbs and a robust, muscular frame that wasn’t designed for the fast running we associate with cats.

Scientists believe it was an ambush predator that relied on strength rather than speed. Its paws were equipped with large claws, though they weren’t retractable like those of cats. The creature likely weighed between 200-400 pounds – about the size of a modern jaguar but with a stockier build.

This bear-like body combined with saber teeth created a predator unlike anything alive today!

7. South American Specialist

Thylacosmilus was exclusively a South American animal, evolving during a fascinating period when the continent was an isolated island. Before the Panama land bridge formed, South America was home to many unique creatures found nowhere else on Earth.

For millions of years, this predator dominated its ecosystem without competition from placental carnivores. When North American predators finally arrived around 3 million years ago (including true saber-toothed cats), Thylacosmilus couldn’t compete and went extinct.

This story highlights how isolation can create evolutionary wonders – and how competition can end even the most spectacular adaptations.

8. Strange Skull Structure

Thylacosmilus had one of the weirdest skull designs in mammal history! To support those massive saber teeth, it evolved bizarre bony flanges that extended downward from its upper jaw, creating a protective framework for the deadly daggers.

Its nasal bones were also unusually positioned, with eye sockets placed high on the skull. The entire skull was reinforced with extra bone density to handle the stresses of its powerful bite.

If you found a Thylacosmilus skull without knowing what animal it belonged to, you might think it came from an alien creature! This extraordinary adaptation shows how evolution can produce truly bizarre solutions to survival challenges.

9. Hunting Style Mystery

How exactly did Thylacosmilus use those enormous fangs? Scientists are still debating! The traditional view suggests it stabbed prey like other saber-tooths, but recent research indicates its unique skull structure might have supported a different hunting technique.

Some paleontologists believe it may have used its powerful neck muscles to drive those sabers downward with tremendous force. Others suggest it might have used them to slash rather than stab, creating devastating wounds that would cause prey to bleed out.

Without observing living specimens, we may never know for certain how this strange predator dispatched its meals – making it one of paleontology’s enduring mysteries.

10. Preferred Prehistoric Prey

Thylacosmilus likely hunted the strange mammals that populated ancient South America. Its preferred menu probably included toxodonts (hippo-like herbivores), macrauchenia (camel-like creatures with trunks), and giant ground sloths that roamed the continent during this time.

Fossil evidence suggests it specialized in taking down prey larger than itself – a strategy that required those impressive fangs and powerful build. The ancient South American savanna was filled with bizarre herbivores found nowhere else on Earth.

Imagine a world where this pouched predator stalked elephant-sized sloths and trunk-nosed ungulates across grasslands that stretched to the horizon!

11. Evolutionary Dead End

Despite its impressive adaptations, Thylacosmilus represents what scientists call an evolutionary dead end. Its highly specialized features worked well in isolation but couldn’t compete when North American predators arrived in South America.

After thriving for millions of years, this unique predator disappeared forever around 3 million years ago. No modern animals carry on its legacy – it has no direct descendants alive today.

This extinction story reminds us that even the most impressive adaptations aren’t guarantees of evolutionary success. Sometimes being too specialized can be a disadvantage when environments and competitors change!

12. Walking On Flat Feet

Unlike cats who walk on their toes (digitigrade), Thylacosmilus walked with its entire foot touching the ground (plantigrade) – similar to how humans, bears, and raccoons walk! This flat-footed stance provided stability and strength rather than speed and agility.

Its feet were equipped with strong, non-retractable claws that helped it grip the ground and potentially hold down struggling prey. The ankle bones show it wasn’t built for quick chases or pouncing.

This walking style, combined with its stocky build, suggests Thylacosmilus was a methodical hunter that relied on ambush tactics rather than pursuing prey over long distances – a stark contrast to the hunting style of modern big cats.

13. Neck Built For Power

The neck of Thylacosmilus was a marvel of evolutionary engineering! Fossil evidence shows it had extremely powerful neck muscles supported by robust vertebrae and unusually long neural spines – bony projections where muscles attach.

This powerful neck likely helped the animal drive its sabers downward with tremendous force. Unlike modern big cats that kill with a precise throat bite, Thylacosmilus probably used its neck strength to deliver devastating stabs or slashes.

Muscle attachment points on the skull and vertebrae suggest a neck perhaps twice as strong as that of a similar-sized modern predator. This neck power was crucial to its hunting strategy and compensated for the relative weakness of its jaw muscles.

14. Unexpected Dental Details

Beyond those famous sabers, Thylacosmilus had other bizarre dental features! Unlike other carnivores, it lacked lower canines completely – they would have just gotten in the way of those massive upper fangs. Its molars were also simplified compared to other predators.

Strangest of all, the saber teeth had no enamel! They were composed entirely of dentin, a softer tooth material. This meant they would wear down with use and needed to grow continuously throughout the animal’s life.

Microscopic wear patterns on the teeth suggest they weren’t used for chewing but primarily for delivering killing blows. This unique dental arrangement has no exact parallel among living or extinct mammals!