The Irish Elk’s Role In Shaping Prehistoric Ecosystems

The Irish Elk, despite its name, wasn’t exclusively Irish nor a true elk – it was actually a giant deer that roamed Eurasia during the Pleistocene epoch.

These magnificent creatures stood taller than a modern moose with antlers spanning up to 12 feet wide, making them the largest deer species ever to exist.

Their impressive size and widespread presence meant they significantly influenced the prehistoric landscapes and ecosystems they inhabited in ways we’re still discovering today.

1. Forest Architects

Standing at an impressive 7 feet tall at the shoulder, Irish Elk literally shaped forests through their feeding habits. Their massive bodies required enormous amounts of vegetation daily – up to 100 pounds per animal!

While browsing, these giants created pathways through dense woodland, opening up corridors that smaller animals could utilize. Their selective feeding patterns promoted certain plant species while suppressing others.

Much like modern elephants, Irish Elk likely knocked down smaller trees to access tender shoots and leaves, creating patchwork clearings in forests that allowed sunlight to reach the forest floor, encouraging biodiversity in prehistoric woodlands.

2. Nutrient Distributors

Irish Elk functioned as walking fertilizer factories across ancient landscapes. Each animal produced roughly 30 pounds of waste daily, depositing essential nutrients throughout their extensive territories.

Plant material consumed in one area would be processed and deposited elsewhere as they traveled, effectively redistributing nitrogen, phosphorus, and other vital elements across ecosystems. This natural fertilization supported plant communities that might otherwise have struggled in nutrient-poor soils.

Seeds also hitched rides in their digestive tracts, allowing plants to colonize new areas far from their origin – a process called endozoochory that shaped plant distribution patterns.

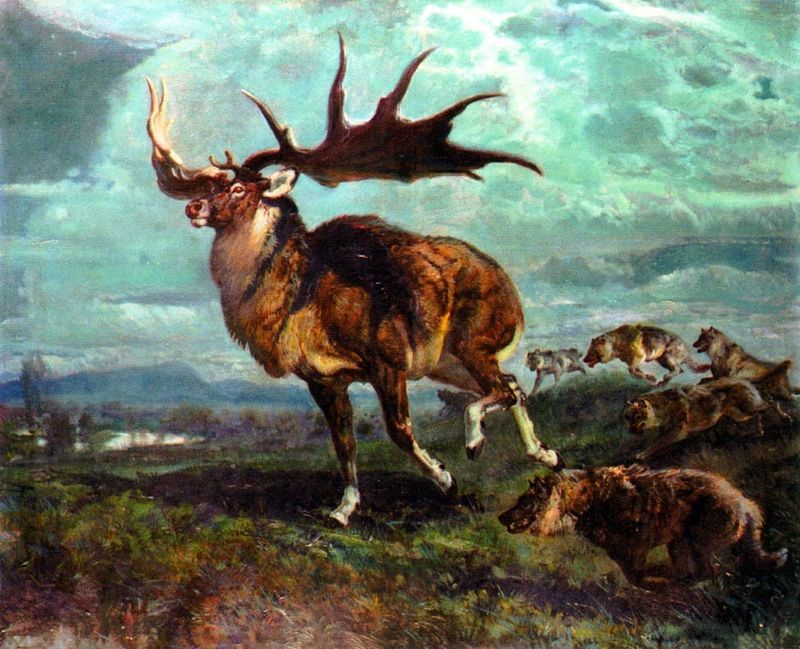

3. Predator Sustainers

Those magnificent antlers weren’t just for show! Male Irish Elk used them for combat during mating seasons, and sometimes these battles proved fatal. The casualties provided crucial food sources for prehistoric predators and scavengers.

Even healthy adults occasionally fell victim to coordinated attacks from wolf packs or cave lions. A single Irish Elk carcass could feed multiple predators for days, supporting the survival of these carnivore populations.

Young, old, or weak individuals were particularly vulnerable, creating a natural selection process that maintained healthier elk populations while simultaneously sustaining the predators that kept the ecosystem balanced.

4. Grassland Maintenance Crew

Grazing pressure from Irish Elk helped maintain open grasslands that might otherwise have transitioned to shrubland or forest. Their massive appetites prevented woody plants from establishing dominance in these areas.

Seasonal migration patterns meant different areas experienced varying grazing intensities throughout the year. This created a mosaic of vegetation heights and densities across the landscape – some heavily grazed, others lightly touched.

Such habitat diversity supported countless other species, from ground-nesting birds to small mammals and specialized insects. Without these giant herbivores, many prehistoric grassland ecosystems would have looked dramatically different.

5. Climate Responders

Fossil evidence reveals fascinating adaptations in Irish Elk during climate shifts. As temperatures changed, so did their body and antler sizes – a phenomenon called Bergmann’s rule, where animals grow larger in colder climates to conserve heat.

During glacial periods, these massive deer concentrated in southern refugia, intensifying their ecological impact in these areas. When warmer periods allowed northward expansion, their influence spread across broader landscapes.

Their responses to climate fluctuations created ripple effects throughout ecosystems. Plant communities adapted to their presence or absence, while predator populations followed their movements – making Irish Elk key players in ecosystem resilience to climate change.

6. Wetland Engineers

Mud-loving Irish Elk frequented prehistoric wetlands, leaving lasting impressions – literally! Their heavy hooves created depressions that collected water, forming microhabitats for amphibians and aquatic plants.

Paths trampled through marshy areas created channels that altered water flow patterns. These natural “ditches” drained some areas while flooding others, creating diverse wetland conditions.

Regular visits to water sources for drinking established well-worn trails that other animals followed. Much like modern elephants in African wetlands, Irish Elk likely maintained open water access points through reed beds and dense vegetation, benefiting countless other species that needed to reach water but couldn’t forge paths themselves.

7. Evolutionary Catalysts

Plants developed fascinating adaptations in response to Irish Elk browsing pressure. Some evolved thorns or toxic compounds to discourage being eaten, while others adapted to quick regrowth after being browsed.

Certain plants may have evolved larger seeds to survive passage through elk digestive tracts, enhancing their dispersal success. This coevolutionary relationship shaped both plant defense strategies and reproductive mechanisms.

Even predators evolved in response to these giant deer – developing pack hunting techniques and specialized killing strategies. The evolutionary arms race between Irish Elk and their environment created cascading adaptations throughout the food web, driving biodiversity development in prehistoric ecosystems.

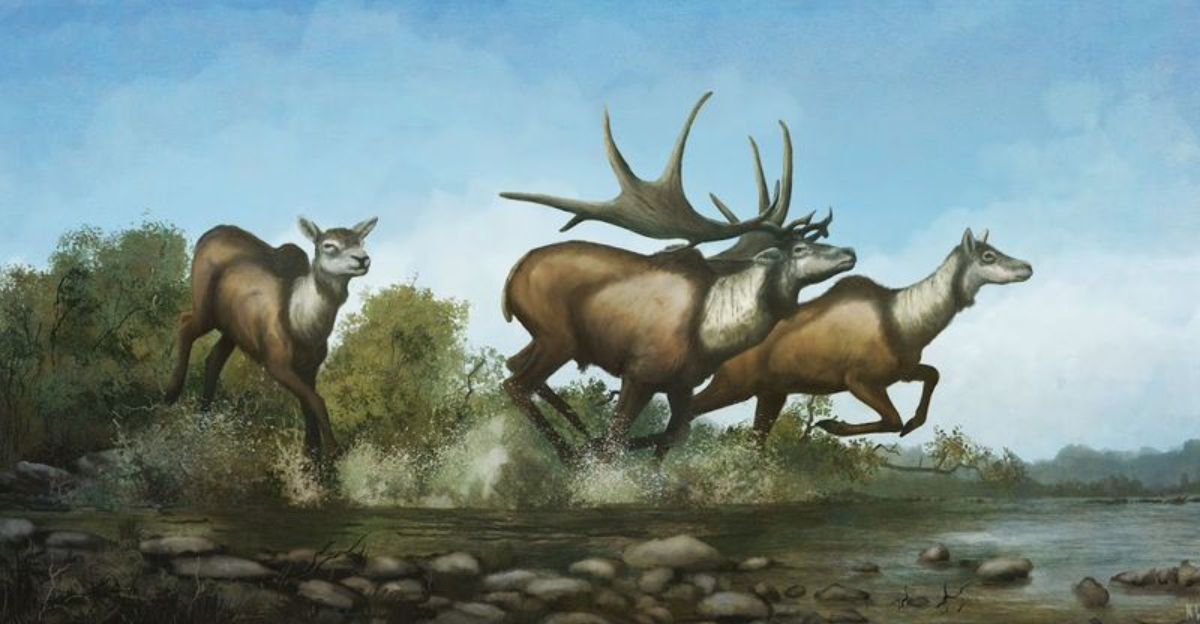

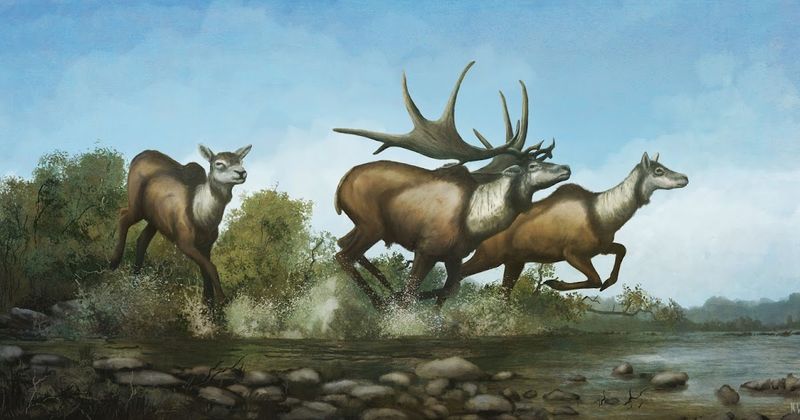

8. Seasonal Migration Influencers

Massive herds of Irish Elk undertook seasonal migrations that transformed landscapes along their routes. These well-trodden paths became natural corridors for other species to follow – from small herbivores to their predators.

During migrations, intense but brief grazing pressure created a “pulse” effect on vegetation. Plants in these corridors evolved specific traits to withstand periodic intensive browsing followed by recovery periods.

River crossings used regularly by migrating elk became important focal points in the landscape. These areas experienced heavy trampling and nutrient enrichment from droppings, creating unique ecological hotspots where specialized plant communities thrived in the disturbed, fertilized soil.

9. Population Boom-Bust Cycles

Irish Elk populations fluctuated dramatically over time, creating fascinating ecological ripple effects. During population explosions, their increased browsing pressure transformed forests into more open woodlands and expanded the edge habitats many species depend on.

When populations crashed – due to disease, climate change, or resource limitations – vegetation patterns shifted again. Previously suppressed plants flourished in their absence, changing the character of entire landscapes.

These boom-bust cycles prevented any single state of ecological equilibrium from dominating. The resulting dynamic mosaic of habitat types supported greater overall biodiversity than would have existed with stable elk populations, demonstrating how population instability can actually enhance ecosystem resilience.

10. Extinction Aftershocks

When Irish Elk vanished approximately 7,700 years ago, they left ecological vacuums that transformed entire ecosystems. Plant species they had kept in check suddenly flourished, while others they had dispersed struggled to spread.

Predators that specialized in hunting these giant deer faced food shortages, forcing adaptation or contributing to their own extinctions. The complex web of species interactions they supported unraveled in what ecologists call “extinction cascades.”

Modern research on their extinction provides valuable insights for conservation biology today. The Irish Elk story demonstrates how losing keystone herbivores triggers far-reaching consequences throughout ecosystems – lessons we’re applying to protect modern elephants, bison, and other ecosystem engineers.