Should We Be Bringing Back Extinct Animals?

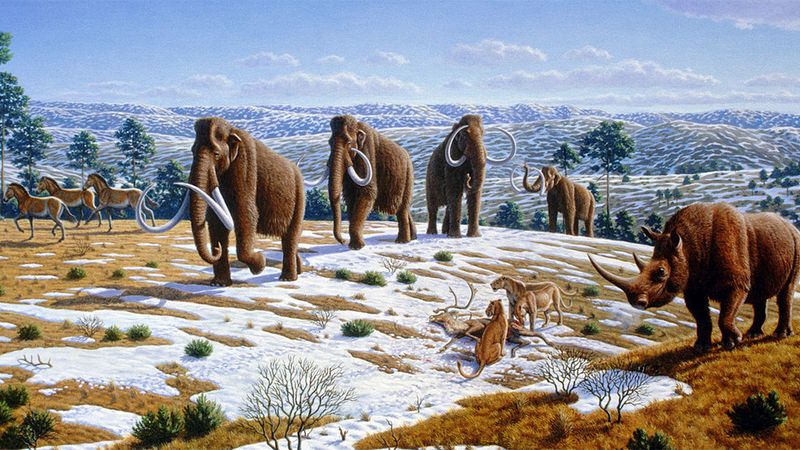

What if woolly mammoths roamed the Earth again? Scientists are getting closer to bringing extinct species back through genetic engineering and cloning.

This controversial practice, called de-extinction, raises fascinating questions about science, ethics, and our responsibility to both lost species and existing ecosystems.

1. Restoring Lost Biodiversity

Extinct animals once played crucial roles in their ecosystems. The passenger pigeon, for instance, helped distribute seeds across North America, contributing to forest health and diversity.

When these species disappeared, they left ecological gaps that still affect environments today. Bringing back extinct species could potentially heal damaged ecosystems and restore natural processes that have been missing for decades or even centuries.

2. Playing With Fire: Unforeseen Consequences

Environments change after species disappear. The woolly mammoth’s former habitat isn’t the same place it was 4,000 years ago – climate, vegetation, and other animal populations have all shifted dramatically.

Reintroducing extinct species might disrupt existing ecological balances. Modern ecosystems have adapted to life without these animals, and their sudden reappearance could create competition for resources or introduce unexpected predator-prey relationships that harm currently thriving species.

3. Scientific Breakthroughs And Learning Opportunities

The quest to revive extinct species drives incredible advances in genetic technology. Scientists developing de-extinction techniques pioneer methods that benefit conservation of endangered species and human medicine alike.

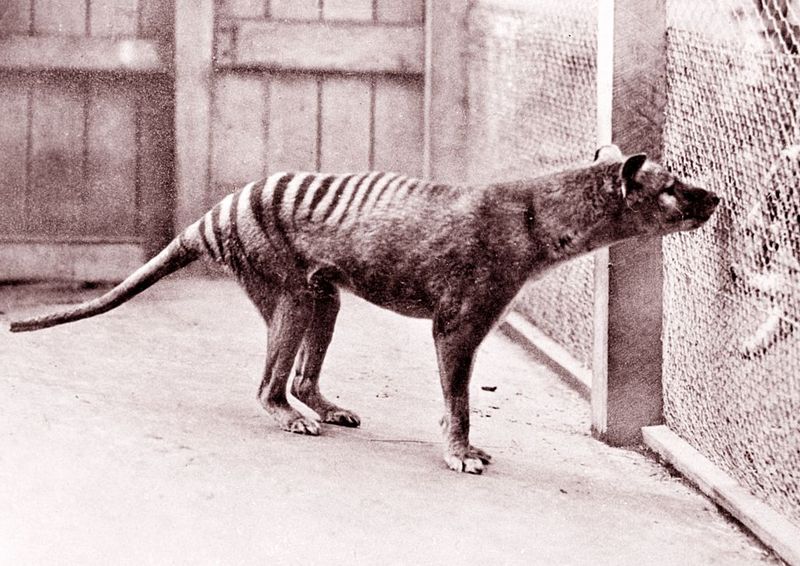

Studying revived extinct animals would provide unprecedented insights into evolution, behavior, and biology that fossils alone can’t reveal. Imagine observing how a thylacine hunts or how a dodo bird raises its young – knowledge previously lost to time forever.

4. Conservation Distraction

Flashy de-extinction projects might divert crucial funding away from protecting currently endangered species. Why spend millions reviving the woolly mammoth when that money could save living elephants from extinction?

Many conservation biologists worry that de-extinction creates a false sense that extinction isn’t permanent, potentially reducing urgency to protect threatened species. “We can always bring them back later” becomes a dangerous mindset that undermines present conservation efforts.

5. Moral Obligation To Undo Human Damage

Humans directly caused many recent extinctions through hunting, habitat destruction, and pollution. The passenger pigeon, once numbering in the billions, was hunted to extinction by 1914.

Many argue we have an ethical responsibility to restore species we eliminated. If technology allows us to undo this damage, shouldn’t we use it? Bringing back animals humans drove to extinction could be viewed as a form of ecological reparation.

6. Animal Welfare Concerns

Resurrected animals would face serious welfare challenges. Early attempts would likely produce individuals with health problems or genetic abnormalities, raising ethical questions about creating suffering.

These creatures would also lack cultural knowledge normally passed down from parents – migration routes, social behaviors, and survival skills. A mammoth wouldn’t instinctively know how to be a mammoth in the modern world, potentially leading to psychological distress and isolation.

7. Public Inspiration For Conservation

The wonder of seeing extinct creatures could spark unprecedented public enthusiasm for conservation. Imagine the awe of watching a living mammoth or dodo – such experiences might transform how people value biodiversity.

This “wow factor” could translate into greater support for protecting all endangered species. De-extinction projects attract media attention and public interest in ways traditional conservation efforts rarely achieve, potentially creating a generation of conservation advocates.

8. Technical Limitations And Authenticity Questions

Current de-extinction methods can’t produce perfect replicas of extinct species. Most approaches create hybrids containing some DNA from related living species – more like genetic approximations than true resurrections.

The passenger pigeon project, for example, uses band-tailed pigeons as templates, adding passenger pigeon genes. But is the resulting animal truly a passenger pigeon? These creatures would be new genetic entities, raising questions about authenticity and what defines a species.

9. Climate Change Fighters

Some extinct species could help combat climate change. Woolly mammoths knocked down trees and compacted snow in arctic regions, potentially helping maintain carbon-capturing grasslands.

Scientists like George Church argue that reintroducing mammoth-like creatures to Siberia could slow permafrost melting by restoring these grasslands. Such “rewilding” projects might offer natural solutions to environmental challenges, turning de-extinction into a climate action tool.

10. Prioritization Problems

With limited conservation resources, which extinct species deserve resurrection? Should we prioritize recently extinct animals or iconic prehistoric creatures? Economic potential often drives these decisions rather than ecological importance.

The woolly mammoth gets attention because it captures imagination, while less charismatic but ecologically vital species remain overlooked. This popularity contest approach risks creating vanity projects rather than meaningful ecological restoration, benefiting only species with public appeal.

11. Cultural And Indigenous Perspectives

Many indigenous cultures maintain spiritual connections to extinct animals. The return of culturally significant species could help restore cultural practices and heal historical wounds for communities that lost traditional relationships with these animals.

However, de-extinction also risks commodifying creatures sacred to some cultures. Indigenous perspectives often remain sidelined in these scientific endeavors, raising questions about who should control the revival of animals with deep cultural significance.

12. Ecosystem Services and Economic Benefits

Revived species could provide valuable ecosystem services with economic benefits. Passenger pigeons might control pest insects, while grazing mammoths could maintain grasslands for carbon sequestration.

Tourism opportunities around de-extinction parks could generate conservation funding while creating jobs. Companies are already investing in de-extinction with these potential returns in mind, viewing extinct species as both ecological and economic assets worth restoring.

13. The Slippery Slope Of Playing God

De-extinction represents unprecedented human intervention in nature. Critics worry this crosses a fundamental boundary, allowing humans to redesign the natural world according to our preferences rather than accepting natural processes.

This power raises profound questions about humanity’s role on Earth. If we can resurrect extinct species, what else might we redesign? The technology behind de-extinction could eventually enable creating entirely new species, fundamentally changing our relationship with nature forever.