Rare Spotted Turtle Conservation Efforts Grow In Ohio Wetland Habitats

Ohio’s wetlands are home to one of nature’s most charming reptiles – the spotted turtle, known for its distinctive yellow-dotted shell.

These small creatures play a vital role in maintaining healthy wetland ecosystems, but their numbers have been declining at an alarming rate.

Across the state, dedicated conservationists, scientists, and everyday citizens are joining forces to protect these rare turtles and their habitats.

Spotted Turtles Are Among Ohio’s Rarest Wetland Creatures

Only a few hundred spotted turtles remain in Ohio’s fragile wetland ecosystems. These palm-sized reptiles, with their distinctive yellow polka dots, have earned a threatened status in the state due to their dwindling population.

Habitat loss has hit these turtles particularly hard. As wetlands are drained for development or agriculture, these specialized creatures lose the shallow, clean waters they depend on for survival.

Female spotted turtles lay just 3-5 eggs annually, making population recovery especially challenging. Their slow reproduction rate means every adult turtle saved represents years of potential offspring for future generations.

These Tiny, Yellow-Spotted Reptiles Are Quietly Disappearing

Measuring just 3-5 inches long, spotted turtles face outsized threats to their survival. Their beautiful yellow-dotted shells make them targets for illegal collection in the pet trade, removing vital breeding adults from wild populations.

Road mortality claims countless turtle lives each year. During spring breeding season, females travel to nesting sites, often crossing dangerous roadways where they’re vulnerable to vehicle strikes.

Climate change disrupts the seasonal wetlands these turtles depend on. Extended droughts dry up critical habitat, while intense storms can flood nesting areas, destroying eggs before they have a chance to hatch.

Shell Rot And Pollution Pose Growing Threats To Their Survival

Agricultural runoff introduces harmful chemicals into wetlands where spotted turtles live. Fertilizers cause excessive algae growth that depletes oxygen levels, while pesticides directly harm turtles’ sensitive systems.

Shell rot, a bacterial or fungal infection, attacks turtles weakened by environmental stressors. The condition creates painful lesions on their shells and skin, leaving them vulnerable to predators and further infection.

Plastic pollution presents a deadly hazard. Turtles mistake floating plastic for food, causing intestinal blockages. Even small amounts of trash can introduce toxins that build up in turtle tissues over their long lifespans.

Conservationists Are Restoring Wetlands To Help Them Bounce Back

Wetland restoration projects across Ohio are recreating the specialized habitats spotted turtles need. Conservation teams remove invasive plants that choke native vegetation and install water control structures to maintain ideal water levels throughout the seasons.

Native plant reintroduction provides critical food sources and shelter. Sedges, rushes, and floating vegetation give turtles places to bask, hide from predators, and hunt for their favorite foods.

Artificial nesting sites offer safe alternatives when natural areas are compromised. These carefully designed sand and gravel beds give female turtles protected places to lay eggs away from predators and human disturbance.

Researchers Use Tracking Devices To Monitor Turtle Health And Movement

Tiny radio transmitters, no larger than a coin, are carefully attached to turtle shells without harming the animals. These devices emit signals that allow researchers to locate turtles hidden among dense vegetation or underwater, revealing previously unknown movement patterns.

GPS tracking has uncovered surprising information about spotted turtle travel distances. Some individuals journey over half a mile between seasonal wetlands, navigating complex landscapes with remarkable precision.

Health assessments during tracking studies provide valuable data on population conditions. Researchers collect blood samples, check for parasites, and measure growth rates, creating a comprehensive picture of how environmental factors affect turtle wellbeing.

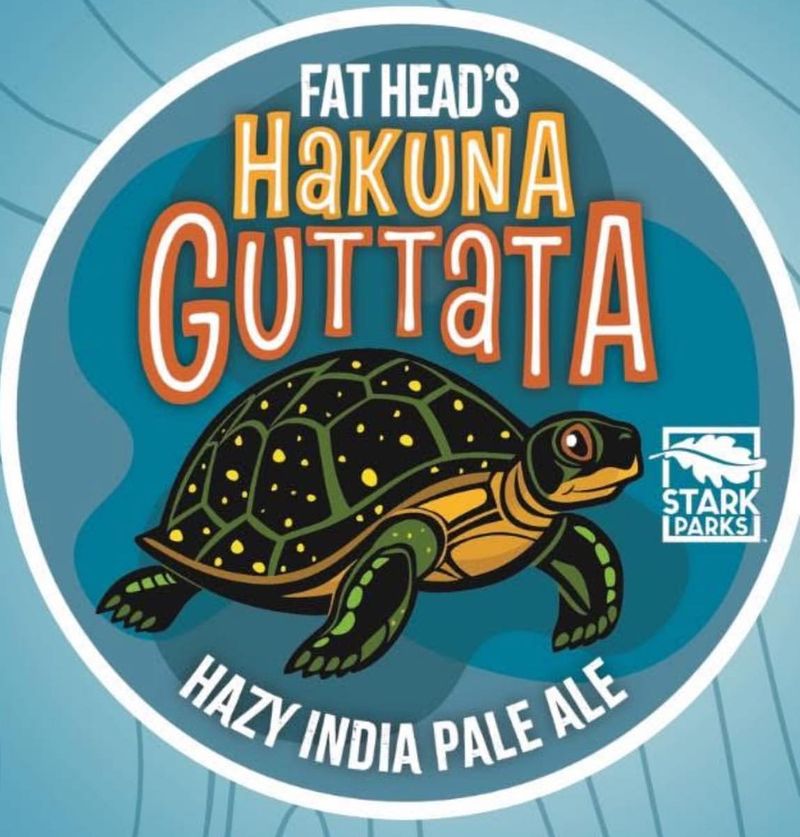

Fat Head’s Brewery Supports The Cause With A Limited ‘Hakuna Guttata’ IPA

Fat Head’s Brewery created a special beer named after the spotted turtle’s scientific name, Clemmys guttata. The limited-edition IPA features artwork of the endangered turtle on its label, instantly recognizable to conservation-minded beer enthusiasts.

Master brewers crafted a unique flavor profile using locally sourced ingredients. The beer incorporates hints of wild blackberry and citrus, reflecting the wetland habitats where spotted turtles thrive.

Each can includes a QR code linking to educational resources about Ohio’s spotted turtles. This clever marketing approach turns every purchase into an opportunity to learn about these threatened reptiles and how to help protect them.

Beer Sales Help Fund Turtle Rehab And Public Education Campaigns

Five percent of all ‘Hakuna Guttata’ IPA sales go directly to turtle rehabilitation centers. These specialized facilities treat injured turtles found with cracked shells from vehicle strikes or suffering from pollution-related illnesses.

Educational programs funded by beer sales reach thousands of Ohio students annually. Interactive presentations bring live spotted turtles to classrooms, creating memorable experiences that foster lifelong conservation values among young people.

Community science initiatives engage everyday citizens in conservation efforts. Volunteers learn to identify and report spotted turtle sightings through user-friendly mobile apps, creating valuable data that helps scientists track population trends across the state.

Why Saving One Turtle Species Matters For Entire Ecosystems

Spotted turtles serve as wetland ecosystem engineers, modifying their habitats in ways that benefit countless other species. Their foraging activities stir up sediment, releasing nutrients and creating microhabitats for aquatic invertebrates and amphibians.

As both predators and prey, these turtles occupy a crucial middle position in the food web. They control insect and snail populations while providing food for larger predators, helping maintain the delicate balance of wetland communities.

Scientists use spotted turtles as indicator species for overall wetland health. Their presence signals clean water and functioning ecosystem processes, while their absence often warns of underlying environmental problems that affect all wetland inhabitants.

Volunteers, Scientists, And Local Businesses Unite To Make A Difference

Weekend wetland cleanup events bring together diverse community members with a shared mission. Families, students, and retirees remove trash and invasive plants from turtle habitats while learning about these fascinating creatures from expert naturalists.

Corporate partnerships provide essential funding for large-scale conservation projects. Engineering firms donate services to design water control structures, while construction companies offer equipment and materials for habitat restoration at reduced costs.

Citizen science programs transform casual nature lovers into valuable data collectors. Trained volunteers conduct turtle surveys during peak activity seasons, greatly expanding the monitoring capacity beyond what professional scientists could accomplish alone.

The Fight To Save Spotted Turtles Is Also A Fight To Protect Ohio’s Wetlands

Wetlands act as natural water filters, trapping sediments and absorbing pollutants before they reach rivers and lakes. By protecting spotted turtle habitats, conservationists simultaneously safeguard drinking water sources for millions of Ohioans.

These ecosystems provide critical flood control services. Healthy wetlands absorb excess rainwater during storms, preventing downstream flooding in communities and agricultural areas across the state.

Carbon sequestration represents another vital wetland function. The rich organic soils in turtle habitats store massive amounts of carbon that would otherwise enter the atmosphere as greenhouse gases, making spotted turtle conservation an unexpected ally in climate change mitigation.