14 Prehistoric Reptiles That Walked The Earth Before Dinosaurs Existed

Long before T-Rex roamed the Earth and even before the first dinosaurs appeared, our planet was home to a fascinating array of reptiles.

These ancient creatures dominated landscapes during the Permian and early Triassic periods, setting the evolutionary stage for the dinosaurs that would follow.

From sail-backed predators to turtle-like herbivores, these prehistoric animals adapted to Earth’s harsh conditions and thrived in ways that still amaze scientists today.

1. Hylonomus: Earth’s First True Reptile

About 315 million years ago, a small lizard-like creature scurried through the swampy forests of what is now Nova Scotia, Canada. Only 20-30 centimeters long, Hylonomus holds the title of the earliest known reptile in fossil records.

Unlike amphibians, this pioneering species could lay eggs with hard shells on land, freeing it from returning to water for reproduction. Its diet likely consisted of small insects and plants that it hunted among prehistoric ferns.

Scientists discovered its remains inside fossilized tree stumps, suggesting these tiny reptiles used hollow logs as shelter from larger predators and harsh weather conditions.

2. Dimetrodon: The Sail-Backed Hunter

Often mistaken for a dinosaur, Dimetrodon actually predated dinosaurs by millions of years. This fearsome predator roamed Earth during the Early Permian period, about 295-272 million years ago, sporting a massive sail on its back made of elongated vertebral spines connected by skin.

Growing up to 3.5 meters long, Dimetrodon dominated its ecosystem as a top predator. Its name means “two measures of teeth” – reflecting its specialized dentition with sharp canines for tearing prey and smaller teeth for gripping.

The distinctive sail likely regulated body temperature, absorbing morning sunlight to warm up quickly and dissipating heat when turned away from the sun.

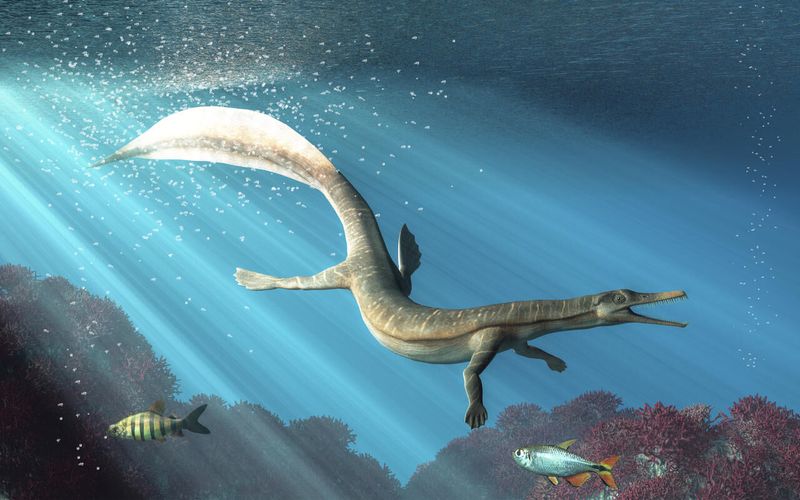

3. Mesosaurus: The Puzzle-Solving Swimmer

Mesosaurus wasn’t just any prehistoric reptile – it helped solve one of geology’s greatest mysteries! Living about 286 million years ago, this meter-long aquatic reptile inhabited freshwater lakes and rivers in what is now South America and Southern Africa.

With needle-like teeth perfect for catching small aquatic prey and a long, paddle-like tail for swimming, Mesosaurus was beautifully adapted for aquatic life. Scientists found identical fossils on both continents, providing crucial evidence for continental drift theory.

These reptiles couldn’t have swum across the Atlantic Ocean, suggesting the continents were once connected in the supercontinent Gondwana before splitting apart over millions of years.

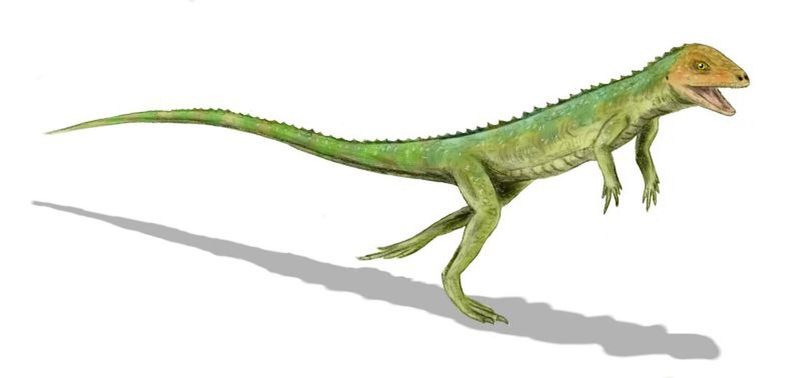

4. Petrolacosaurus: The Diapsid Pioneer

Meet the grandfather of modern reptiles! Petrolacosaurus lived around 302 million years ago during the Late Carboniferous period. This slender, agile creature measured about 40 centimeters long – similar to today’s large lizards.

What makes Petrolacosaurus special is its skull structure. It was one of the earliest diapsids – reptiles with two holes in each side of the skull behind the eyes. This evolutionary innovation allowed for stronger jaw muscles and better bite force.

The diapsid skull design proved so successful that it evolved into numerous reptile lineages including dinosaurs, crocodiles, lizards, snakes, and even birds! Petrolacosaurus essentially launched the reptilian dynasty that would dominate Earth for hundreds of millions of years.

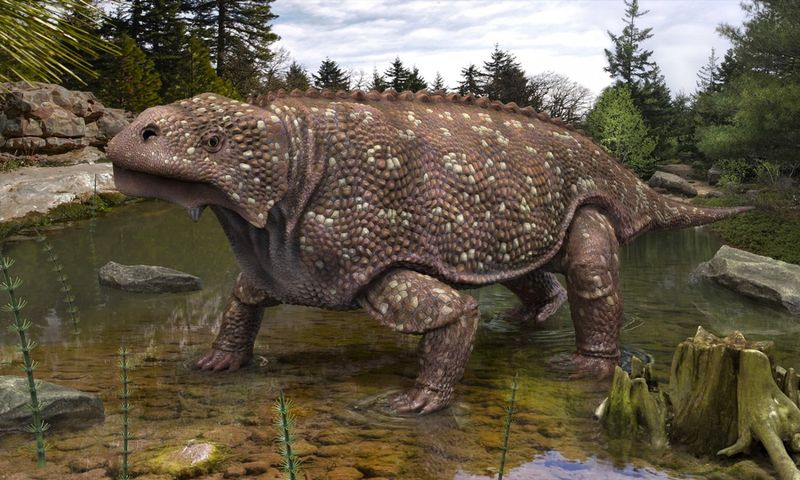

5. Bradysaurus: The Tank-Like Plant Eater

Bradysaurus was the prehistoric equivalent of a living tank. Lumbering across the landscape about 260 million years ago during the Middle Permian, this hefty herbivore belonged to a group called pareiasaurs – large, heavily-built reptiles with thick skulls and bony armor embedded in their skin.

Growing up to 2.5 meters long with a barrel-shaped body, Bradysaurus had a small head with leaf-shaped teeth perfect for stripping vegetation. Its name means “slow lizard” – an appropriate description for this plodding plant-eater.

Despite its defensive advantages, Bradysaurus eventually vanished during the end-Permian mass extinction. However, some scientists believe pareiasaurs might be distant relatives of modern turtles, based on similarities in their skull structure.

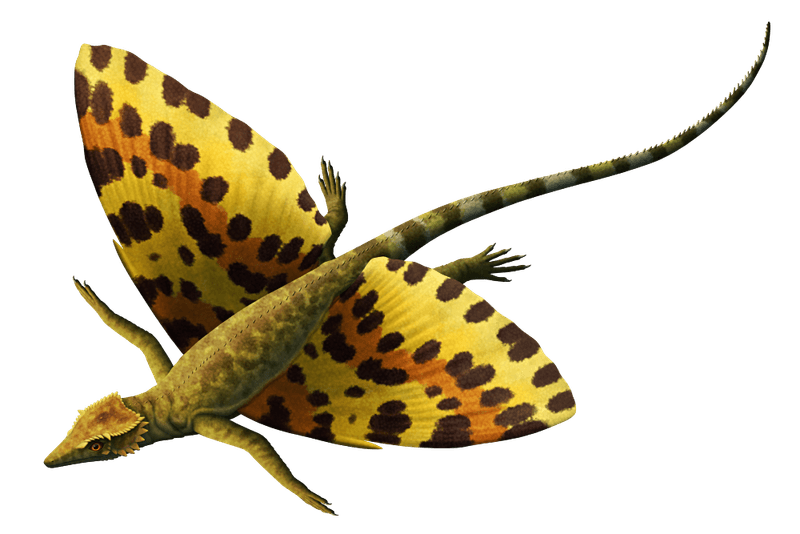

6. Coelurosauravus: The Gliding Wonder

Imagine a reptile that could glide through prehistoric forests 260 million years ago! Coelurosauravus achieved this remarkable feat long before pterosaurs or birds evolved flight. This cat-sized reptile possessed extraordinary rod-like structures extending from its ribs, supporting a membrane that formed primitive wings.

Unlike modern gliding animals whose wings connect to their limbs, Coelurosauravus developed an entirely unique adaptation. It likely launched from high branches, gliding between trees to escape predators or find food in the dense Permian forests.

Fossil discoveries in Madagascar and Germany suggest these creatures were widespread across the ancient supercontinent Pangaea. Their specialized gliding adaptation represents one of evolution’s many experiments with aerial locomotion that appeared independently multiple times throughout Earth’s history.

7. Protorosaurus: The “First Lizard” That Wasn’t

Despite its name meaning “first lizard,” Protorosaurus wasn’t actually a lizard at all! This slender, agile reptile lived around 258-252 million years ago during the Late Permian period. Growing up to 2 meters long, it had a small head, long neck, and powerful limbs built for running.

Protorosaurus belongs to an early group of archosauromorphs – reptiles that would eventually give rise to dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and crocodilians. Its fossils, first discovered in Germany in the 1700s, represent some of the earliest scientific studies of prehistoric reptiles.

Unlike many contemporary reptiles that sprawled with limbs to the side, Protorosaurus showed a more upright posture – an early step toward the efficient locomotion that would later help dinosaurs dominate the planet.

8. Scutosaurus: The Armored Giant

Scutosaurus was practically a walking fortress! This massive herbivore from the Late Permian period (about 254-252 million years ago) grew up to 3 meters long and weighed as much as a small car. Its most distinctive feature was the extensive bony armor covering its body – including thick plates and spiky projections.

The name Scutosaurus means “shield lizard,” referring to its impressive defensive adaptations. Living in what is now Russia, these creatures traveled in herds across semi-arid plains, grazing on tough vegetation with their specialized teeth.

Despite their formidable armor, Scutosaurus couldn’t survive the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event that wiped out nearly 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates about 252 million years ago.

9. Claudiosaurus: The Water-Loving Transitional Form

Claudiosaurus represents a fascinating evolutionary link between early reptiles and the later marine reptiles that would dominate the oceans. Living around 255 million years ago in the Late Permian, this meter-long reptile inhabited coastal areas of what is now Madagascar.

With a long neck, paddle-like limbs, and a tail adapted for swimming, Claudiosaurus was equally comfortable in water and on land. Its fossil discoveries show a creature caught in evolutionary transition – not fully aquatic but showing clear adaptations for marine life.

Scientists believe Claudiosaurus might be related to the ancestors of plesiosaurs – the long-necked marine reptiles that would later thrive alongside dinosaurs. Its discovery helps fill crucial gaps in understanding how fully terrestrial reptiles gradually returned to the sea.

10. Milleretta: The Anapsid Survivor

While many prehistoric reptiles had skulls with openings behind the eyes, Milleretta belonged to a different group. This cat-sized reptile from the Late Permian period (about 260-252 million years ago) was an anapsid – having a solid skull without temporal openings – similar to modern turtles.

Found in South Africa, Milleretta likely fed on insects and small animals in its woodland habitat. With a stocky body and sturdy limbs, it wasn’t built for speed but rather for steady, deliberate movement through its environment.

Milleretta and its relatives represent an important branch of early reptile evolution. While most anapsid groups vanished during the Permian-Triassic extinction, turtles – with their similar skull structure – survived and continue to thrive today as living representatives of this ancient reptile lineage.

11. Planocephalosaurus: The Early Sphenodontian

Planocephalosaurus might not look remarkable at first glance, but this small reptile from the Late Triassic period (about 228-200 million years ago) belongs to an incredibly important evolutionary group. At roughly 30 centimeters long, this insect-eater lived in what is now England when dinosaurs were just beginning to appear.

As an early sphenodontian, Planocephalosaurus was related to the ancestors of today’s tuatara – a living fossil found only in New Zealand. Unlike most reptiles that replace their teeth throughout life, sphenodontians have teeth fused to their jaw bone.

During the Triassic, these reptiles were diverse and widespread, but eventually lost ground to lizards. Today, the tuatara is the sole survivor of this once-successful reptile lineage that predates most dinosaurs.

12. Eudibamus: The First Bipedal Runner

Long before dinosaurs perfected the art of bipedal running, a small reptile was already racing around on two legs! Eudibamus lived during the Early Permian period, about 290 million years ago, in what is now Germany. At just 25 centimeters long, this agile creature could sprint on its hind legs at surprising speeds.

Belonging to a group called bolosaurids, Eudibamus had hind limbs longer than its forelimbs – an adaptation for quick bipedal movement. This running style evolved independently from the later bipedalism seen in dinosaurs, showing how evolution often finds similar solutions to survival challenges.

Scientists believe Eudibamus used its speed to escape larger predators in its environment, demonstrating that bipedal running evolved at least 60 million years earlier than previously thought.

13. Eunotosaurus: The Proto-Turtle Puzzle

Eunotosaurus represents one of paleontology’s most fascinating evolutionary puzzles. Living around 260 million years ago during the Middle Permian, this strange reptile had broad, expanded ribs that created a primitive shell-like structure – leading many scientists to consider it an important transitional form in turtle evolution.

About 30 centimeters long, Eunotosaurus had a short, broad body with nine pairs of widened ribs that overlapped to form a rigid trunk. Unlike modern turtles, it still had teeth and couldn’t retract its head.

Found in South Africa, Eunotosaurus helps illustrate how the turtle’s unique body plan might have evolved. The expanded ribs likely provided protection while digging or burrowing before eventually developing into the complete shell we see in turtles today.

14. Tetraceratops: The Possible Proto-Mammal Relative

Tetraceratops blurs the line between reptiles and the ancestors of mammals. Living about 275 million years ago during the Early Permian, this dog-sized creature had a mix of features that make it difficult to classify. Its name means “four-horned face” due to the hornlike projections on its skull.

Some paleontologists consider Tetraceratops to be a therapsid – a group of synapsid reptiles that includes the direct ancestors of mammals. Its specialized teeth and jaw structure show adaptations moving toward the mammalian condition.

Known from a single fossil skull found in Texas, Tetraceratops provides a tantalizing glimpse of the transition between reptile-like animals and the lineage that would eventually give rise to mammals. This evolutionary branch was separate from the one leading to dinosaurs and modern reptiles.