Meet Patagotitan, The Titanosaur That Changed Our Understanding Of Dinosaur Size

Imagine a creature so massive that it would peek into a five-story building, weighing as much as a dozen elephants combined! That’s Patagotitan mayorum, the colossal titanosaur discovered in Argentina that rewrote our dinosaur history books.

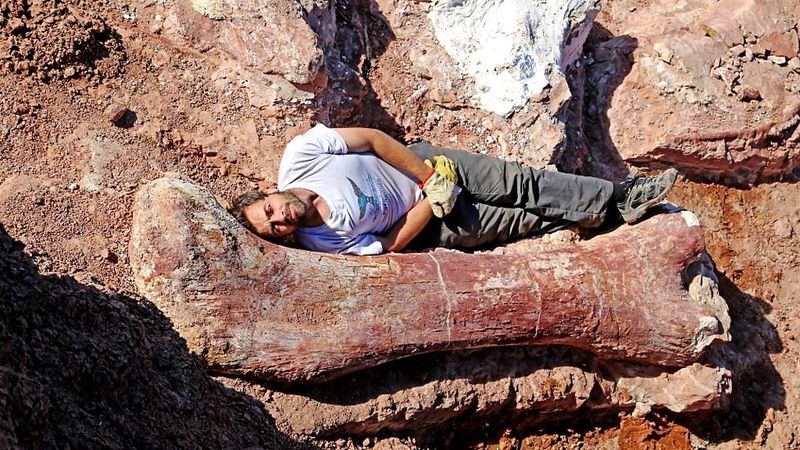

Found in 2010 by a farm worker who stumbled upon what turned out to be one of the most complete giant dinosaur skeletons ever unearthed, this behemoth has fascinated scientists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike with its mind-boggling proportions.

Record-Breaking Discovery

A simple farm worker named Aurelio Hernandez made paleontological history when his shovel hit something unusual in Patagonia, Argentina. Little did he know he’d stumbled upon bones belonging to what would become known as the largest dinosaur ever discovered with scientific certainty.

The excavation that followed revealed a treasure trove of over 200 fossilized bones from at least six individual Patagotitan specimens. This remarkable find gave scientists an unprecedented look at these giants, with about 70% of the skeleton represented – extraordinarily complete for a dinosaur of this size.

The Weight Of A Boeing 737

Tipping the prehistoric scales at an estimated 69 tons, Patagotitan was heavier than a fully-loaded Boeing 737 airplane! This titanosaur’s weight calculations astonished scientists who previously thought land animals had stricter size limitations.

For comparison, the famous Brachiosaurus weighed around 30-45 tons, making Patagotitan potentially 50% heavier. The African elephant, today’s largest land animal, weighs a mere 6-7 tons – meaning it would take about 10 elephants to equal one Patagotitan.

Longer Than A Basketball Court

From nose to tail, Patagotitan stretched approximately 120 feet – longer than a standard NBA basketball court is wide! Standing 20 feet tall at the hip, this gentle plant-eater would tower over your house.

The neck alone measured about 37 feet long, allowing Patagotitan to reach the tops of prehistoric trees without moving its massive body. Its tail, equally impressive, helped balance its enormous weight and may have served as protection against predators.

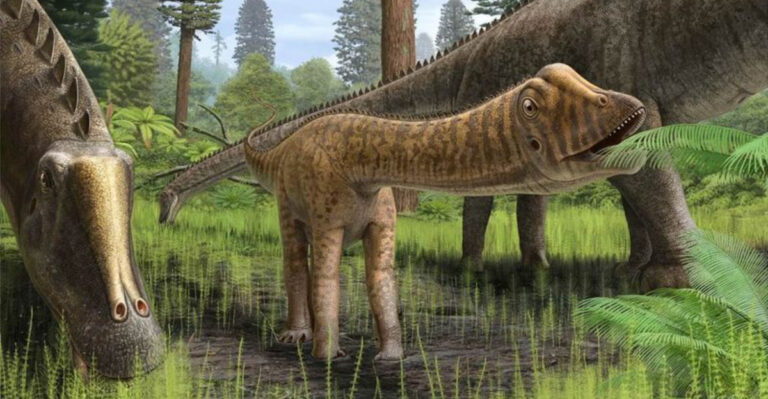

Cretaceous Vegetarian Giant

Despite its intimidating size, Patagotitan was a gentle plant-eater that roamed Earth during the Late Cretaceous period, roughly 100 million years ago. The landscape it inhabited was vastly different from today’s Argentina – a lush, warm forest environment perfect for supporting enormous herbivores.

Scientists believe these giants consumed hundreds of pounds of vegetation daily just to sustain themselves. Their peg-like teeth were specialized for stripping leaves rather than chewing, suggesting they swallowed food whole and processed it in their massive digestive systems.

Heart The Size Of A Small Car

Pumping blood throughout Patagotitan’s enormous body required a heart of extraordinary proportions – scientists estimate it may have been the size of a small car! This powerful organ had to generate enough pressure to push blood all the way up that 37-foot neck to the brain.

The circulatory system of these giants remains one of paleontology’s most fascinating puzzles. Some researchers believe they might have had specialized valves or multiple “heart-like” structures to maintain blood pressure. Their slow metabolism likely helped manage the immense energy demands of their massive bodies.

Baby Giants Grew Incredibly Fast

Hatching from eggs no bigger than footballs (physical limitations prevented larger eggs), baby Patagotitans experienced growth rates that would make human parents jealous. Analysis of bone rings shows these titanosaurs may have grown from 7-pound hatchlings to 10-ton teenagers in just 15 years!

This rapid growth helped vulnerable youngsters quickly reach sizes that deterred predators. Paleontologists believe juvenile Patagotitans likely lived in herds for protection until reaching more formidable sizes.

Museum Sensation Too Big For Display

When the American Museum of Natural History unveiled its Patagotitan cast in 2016, they faced an amusing architectural problem – the dinosaur was too large for any single gallery! The solution? The titanosaur’s neck and head extend through a doorway into an adjacent room, greeting visitors from two separate spaces.

Creating the cast was itself a monumental task. The original fossils were too heavy to transport internationally, so paleontologists created lightweight fiberglass replicas. These replicas now tour museums worldwide, inspiring awe wherever they go.

Named After Its Homeland And Discoverers

The name “Patagotitan mayorum” tells a story all its own. “Patago” honors Patagonia, the region in Argentina where it was discovered. “Titan” references the Greek Titans, primordial giants of mythology – a fitting nod to this dinosaur’s colossal size.

“Mayorum” pays tribute to the Mayo family who owned the farm where the fossils were found and welcomed researchers onto their land. This naming tradition in paleontology recognizes both geography and the people who make discoveries possible.

Engineering Marvels On Legs

How did Patagotitan support its massive weight without collapsing? The answer lies in its remarkable skeletal adaptations. Its leg bones were columnar and extraordinarily thick, resembling elephant legs but on a much grander scale.

Titanosaurs like Patagotitan had specialized vertebrae filled with air sacs, making their massive frames surprisingly lightweight for their size. These adaptations, combined with their wide-set stance, distributed weight efficiently across their four tree trunk-like legs.

Redefining Size Limitations

Before Patagotitan, scientists thought Argentinosaurus held the title of largest dinosaur at roughly 80-100 feet long. The discovery of Patagotitan with its more complete skeleton provided stronger evidence for truly gigantic dinosaurs, sparking renewed debate about maximum possible sizes for land animals.

Biomechanical studies suggest we may have found the upper limit – any larger and bones would break under their own weight. Yet paleontologists remain open to the possibility that even bigger dinosaurs await discovery, hiding in rock formations somewhere on Earth.