10 Invasive Bird Species Non-Native To America (And 5 That Are Native)

Birds play crucial roles in ecosystems worldwide, but when non-native species invade new territories, they can wreak havoc on delicate environmental balances.

Invasive birds often outcompete native species for food, nesting sites, and territory, sometimes leading to population declines of indigenous birds.

Understanding the difference between non-native invaders and America’s native feathered residents helps us appreciate the importance of conservation and ecosystem management.

1. European Starling

Released in New York’s Central Park in 1890 by Shakespeare enthusiasts, European Starlings now number over 200 million across North America.

These glossy, speckled birds aggressively steal nesting cavities from native woodpeckers, bluebirds, and swallows. Their massive flocks damage crops and spread disease, making them one of America’s most destructive avian invaders.

2. House Sparrow

First introduced to Brooklyn in 1851, these small brown birds have become fixtures in American cities and farms. Fiercely territorial, House Sparrows attack and kill native bluebirds and swallows.

They’ve contributed to sharp declines in Eastern Bluebird populations by commandeering nesting boxes specifically designed for these native species. Their adaptability to human environments has fueled their invasive success.

3. Myna Bird

With their striking yellow eye patches and chocolate-brown bodies, Common Mynas have established footholds in Florida and California after escaping captivity.

Native to southern Asia, these intelligent birds drive away local species through aggressive behavior. They’re particularly problematic in Hawaii, where they threaten endangered native birds by competing for nesting sites and food resources while spreading invasive plant seeds.

4. Ring-Necked Pheasant

Sporting iridescent green heads and distinctive white neck rings, these game birds were deliberately introduced from Asia in the 1880s for hunting. Their popularity with hunters has led to continued releases across America.

Ring-necked pheasants trample native prairie vegetation and prey on ground-nesting birds’ eggs. Despite their beauty, they’ve contributed to prairie ecosystem disruption and compete with native quail and grouse.

5. Common Pigeon (Rock Pigeon)

Brought to North America by European settlers in the 1600s, these gray birds with iridescent neck feathers have conquered cities nationwide. Pigeons adapt remarkably well to urban environments, nesting on buildings that mimic their native cliff habitats.

Their droppings damage buildings and spread disease. Despite their familiarity, these birds displace native species like cliff swallows and compete with local birds for limited urban food resources.

6. Monk Parakeet

Bright green with gray foreheads, these South American natives escaped the pet trade to establish wild colonies in Florida, Texas, and several northern states. Unlike most parrots, Monk Parakeets build massive communal stick nests on power lines and transformers.

These nests cause power outages and equipment damage costing millions annually. Their noisy flocks and aggressive feeding habits threaten native fruit-eating birds while damaging crops and gardens.

7. Japanese White-Eye

Tiny but mighty, these olive-green birds with distinctive white eye rings were introduced to Hawaii in 1929 to control insects. They’ve since spread throughout the islands, outcompeting native Hawaiian honeycreepers for food.

Japanese White-eyes also spread invasive plant seeds across fragile island ecosystems. Their role in transmitting avian diseases has further contributed to the decline of Hawaii’s unique native birds, many of which are now endangered.

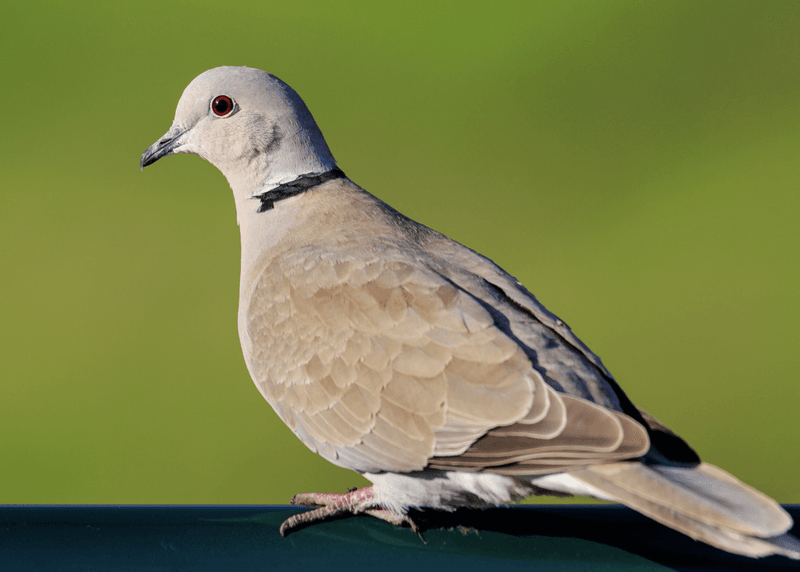

8. Eurasian Collared-Dove

Accidentally released in the Bahamas in the 1970s, these pale gray doves with distinctive black neck rings reached Florida by the 1980s and now inhabit most of North America. Their rapid spread is among the fastest documented for any bird species.

Larger than native mourning doves, they dominate feeding areas and displace local birds. Their year-round breeding gives them a competitive advantage, allowing populations to grow exponentially in newly colonized areas.

9. Cattle Egret

Originally from Africa, these white herons with orange-buff plumes appeared in Florida in the 1940s after naturally crossing the Atlantic. They’ve since spread across the continent, following cattle and farm equipment that flush insects.

Cattle egrets compete with native herons and egrets for nesting sites in wetland rookeries. Their aggressive behavior allows them to dominate feeding areas, pushing out native wading birds from prime foraging locations.

10. Mute Swan

Majestic white birds with orange bills and black facial knobs, Mute Swans were imported from Europe in the 1800s for ornamental display. Escaped birds established wild populations along the Atlantic Coast and Great Lakes.

These aggressive swans attack native waterfowl and even people during nesting season. Their voracious appetite for aquatic vegetation—up to 8 pounds daily—destroys habitat needed by fish and native birds while uprooting crucial wetland plants.

11. Bald Eagle

Soaring with a seven-foot wingspan, our national bird represents American wilderness and resilience. Nearly lost to DDT poisoning by the 1960s, bald eagles have rebounded from just 417 breeding pairs to over 10,000 today.

These powerful raptors with white heads and yellow beaks build massive nests in tall trees near water. Their comeback story showcases successful conservation through pesticide bans, habitat protection, and breeding programs.

12. Northern Cardinal

Flashing brilliant red plumage against winter snow, male Northern Cardinals bring color to backyards across eastern and central United States. Females sport subtle tan-olive coloration with reddish accents.

These year-round residents mate for life and sing throughout the year. Cardinals have thrived alongside human development, actually expanding their range northward in recent decades as winter bird feeding and suburban landscaping create favorable habitat.

13. American Robin

With rusty-orange breasts and cheerful morning songs, American Robins announce spring’s arrival across the continent. These adaptable thrushes hop across lawns hunting for earthworms and nest in trees from Alaska to Mexico.

Robin populations remain strong despite urbanization, as they readily adapt to human landscapes. Their familiar presence in parks and yards makes them among America’s most recognized native birds, connecting people to nature even in cities.

14. Mourning Dove

Named for their soft, mournful cooing, these gentle doves create a peaceful soundtrack across American landscapes. Their slender bodies and pointed tails create distinctive silhouettes against evening skies.

Despite being America’s most hunted bird, with nearly 20 million harvested annually, mourning dove populations remain robust. Their ability to produce multiple broods yearly—sometimes six clutches in southern states—helps maintain healthy numbers across diverse habitats from deserts to suburbs.

15. Red-Shouldered Hawk

Sporting rusty-red shoulders and barred black-and-white wings, these medium-sized hawks patrol eastern and California woodlands with distinctive whistled “kee-aah” calls. Unlike many raptors, red-shouldered hawks often remain in the same territory year-round.

They hunt from perches in forest edges and swamps, controlling rodent populations naturally. Though once declining due to habitat loss, these beautiful hawks have adapted to suburban woodlots and even nest in some city parks, demonstrating remarkable resilience.