How Humans Wiped Out New Zealand’s Giant Birds In Just 300 Years

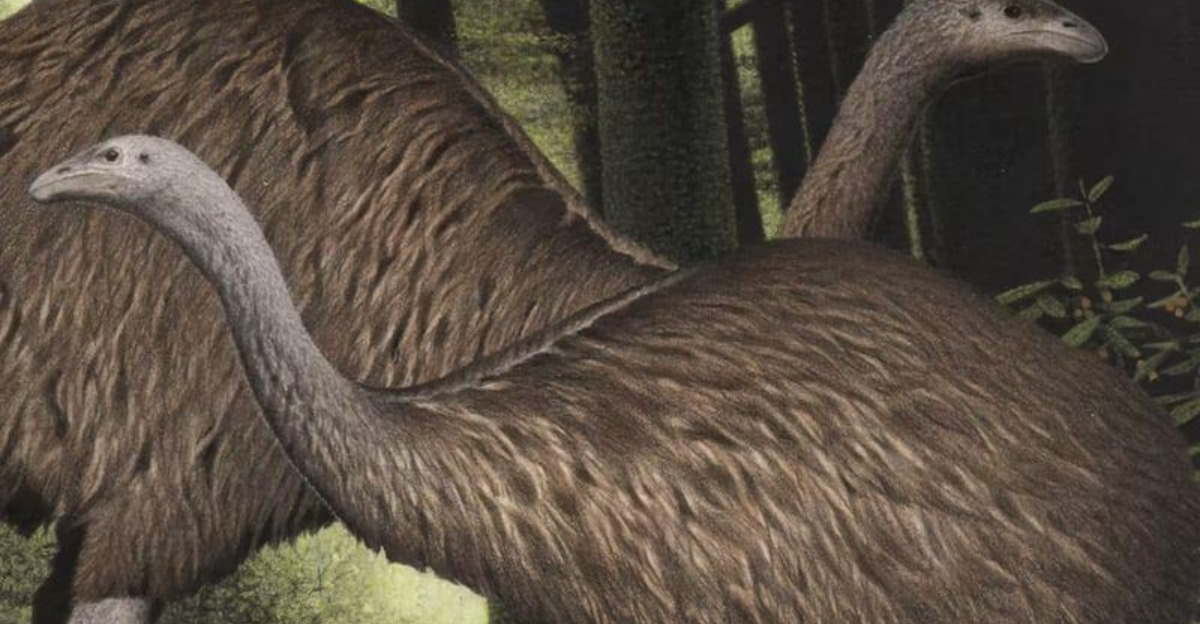

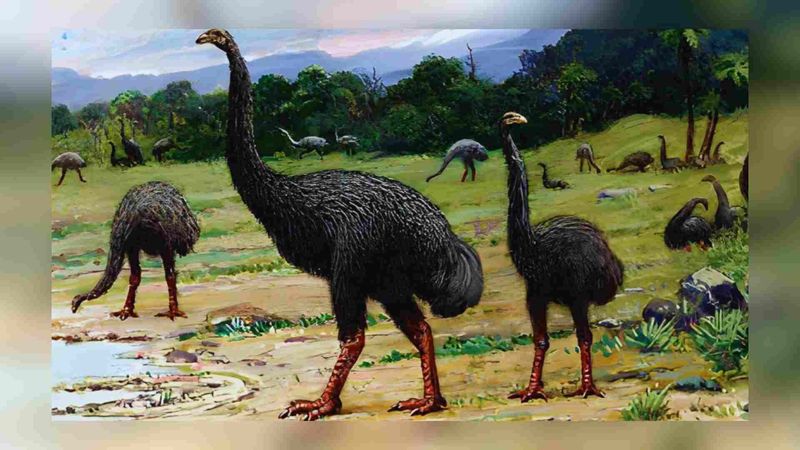

The tragic extinction of New Zealand’s giant birds, the Moa, within just three centuries of human arrival is a story of environmental impact and human intervention.

These towering, flightless creatures once roamed the lush landscapes, playing crucial roles in the ecosystem.

Here are 9 key insights into how human activities led to their demise, shedding light on a fascinating yet cautionary chapter of natural history.

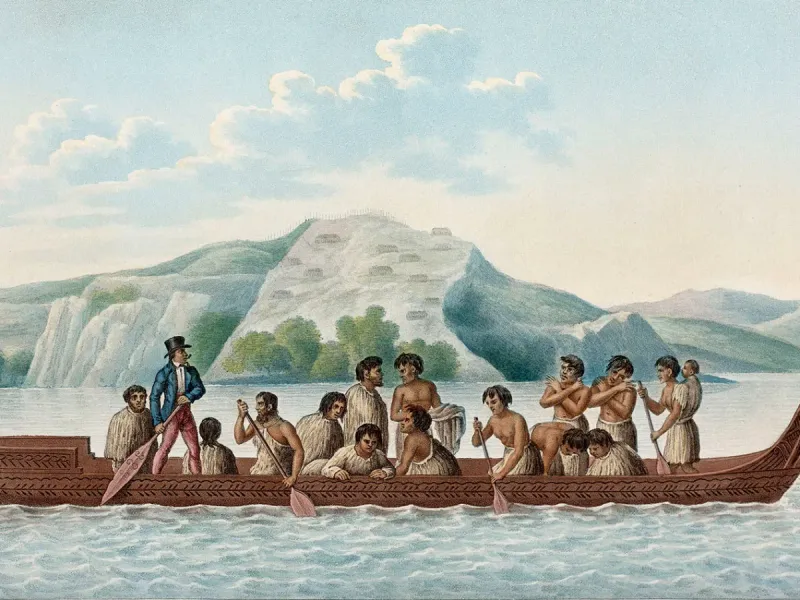

1. Arrival Of Maori Settlers

When the first Polynesian settlers, known as the Maori, arrived in New Zealand around the 13th century, they entered a land untouched by humans.

The Moa, large flightless birds, became an immediate target for hunting. For the Maori, Moas were a valuable resource, providing meat, feathers, and bones.

The birds were hunted extensively for food and materials. The arrival of humans disrupted the island’s delicate ecosystem.

Without natural predators, the Moa had thrived, but they were unprepared for human hunters. This marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the Moa population.

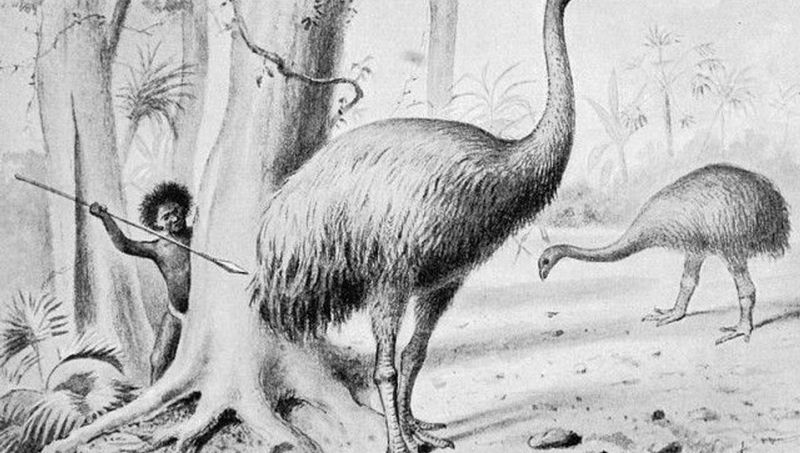

2. Overhunting For Food

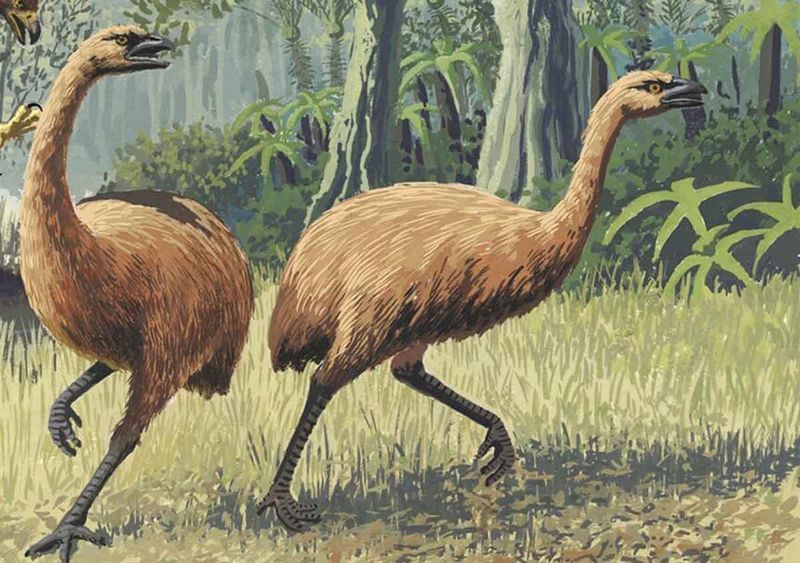

The Moas were quickly overhunted by the Maori settlers due to their large size and slow nature. With no defense mechanisms, these birds were easy prey. Their meat was considered a delicacy, leading to intense hunting.

The Moa’s inability to fly made them particularly vulnerable. They were hunted faster than they could reproduce, causing their numbers to plummet.

The lack of sustainable hunting practices meant that once a population was depleted, there was little chance for recovery. Over time, this relentless hunting pressure led to their extinction.

3. Habitat Destruction

Habitat destruction was another critical factor in the Moa’s extinction. As Maori settlers burned forests to clear land for agriculture, the natural habitat of the Moa was destroyed.

The birds lost their feeding grounds and nesting areas. This deforestation altered the ecosystem drastically, affecting not just the Moa but other species, too.

With fewer places to forage and reproduce, Moas struggled to survive. The loss of their natural environment compounded the effects of hunting, accelerating their decline.

Their habitat, once lush and abundant, became increasingly scarce.

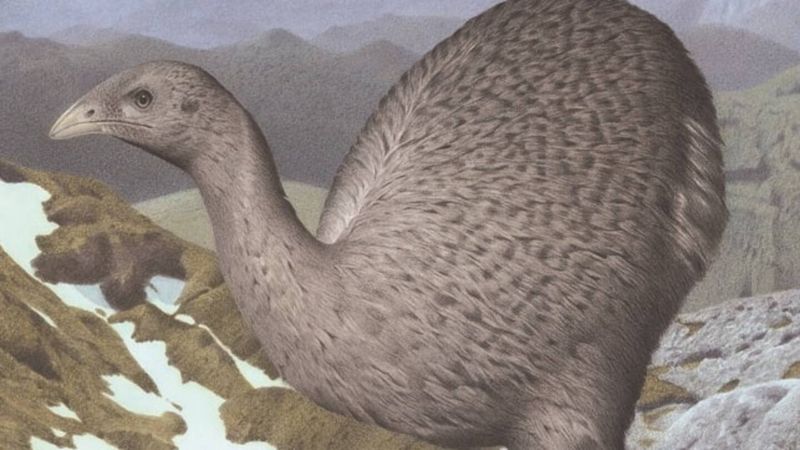

4. Slow Reproduction Rates

Moas had slow reproduction rates, laying only a few eggs at a time, which made them highly susceptible to extinction. Unlike other birds, Moas took longer to reach maturity, further slowing population growth.

The combination of overhunting and habitat loss meant that the few surviving Moas struggled to maintain their numbers.

Each lost egg or chick had a significant impact on the population. This slow breeding cycle couldn’t keep pace with the rate of decline caused by human activities.

The Moa’s biological limitations were a critical factor in their inability to recover.

5. Lack Of Natural Predators

Before humans arrived, Moas lived in a predator-free environment, which contributed to their large size and slow movements. They evolved without the need for defense mechanisms against predators.

This lack of natural threats allowed them to flourish in the diverse New Zealand landscapes. However, it also left them unprepared for the arrival of human hunters.

The sudden introduction of a predator – humans – changed everything. The Moa’s natural defenses were inadequate against human hunting techniques, making them easy targets.

Their inability to adapt quickly to this new threat played a significant role in their extinction.

6. Cultural Significance

For the Maori, Moas held cultural significance beyond just a food source. They were featured in myths and legends and were depicted in traditional art. The birds were considered symbols of strength and resilience.

Their bones were used in tools and their feathers in ceremonial garments. This cultural reverence, however, didn’t prevent their overexploitation.

As their numbers dwindled, Moas became legendary, woven into the cultural fabric of Maori society. The stories of Moa hunts and their majestic presence lived on even after the birds disappeared.

Their significance in Maori culture remains an ironic reminder of their extinction.

7. Environmental Impact

The extinction of Moas had a profound impact on New Zealand’s environment. As large herbivores, they played a key role in maintaining the ecological balance. Their grazing patterns helped shape the vegetation.

Without them, certain plant species proliferated unchecked, altering the landscape. The absence of Moas also affected other species dependent on them.

This ecological shift highlights the interconnectedness of species within an ecosystem. The Moa’s disappearance serves as a reminder of how human actions can trigger cascading effects in nature.

The environmental changes they left behind are still evident today.

8. Scientific Discoveries

The study of Moa fossils has provided valuable insights into their biology and the factors leading to their extinction.

Modern scientific techniques allow researchers to analyze the DNA of the Moa, helping to reconstruct their evolutionary history.

These discoveries shed light on how these birds once lived and thrived. Scientists continue to learn about the environmental conditions of prehistoric New Zealand.

The research has broader implications for understanding extinction events and biodiversity loss. Each fossil fragment tells a part of the Moa’s story, contributing to a deeper understanding of past ecosystems and human impact.

9. Lessons For Conservation

The extinction of the Moa offers valuable lessons for modern conservation efforts. It serves as a cautionary tale about the consequences of overexploitation and habitat destruction.

Conservationists use the extinction of the Moa as a case study to emphasize the importance of sustainable practices. Protecting biodiversity and preventing similar extinctions are key takeaways.

Today’s conservation strategies focus on balancing human needs with environmental protection.

By learning from the past, we can work towards a future where ecosystems are preserved and species thrive. The Moa’s story is a powerful reminder of the delicate balance between humans and nature.