How A Japanese Aquarium Ensured The Happiness Of A Lonely Sunfish

At Japan’s Kaikyokan aquarium, staff noticed something unusual – their sunfish had stopped eating and kept rubbing against the tank walls.

While initially worried about illness, they discovered a surprising cause: the sunfish was lonely!

With the aquarium closed for renovations, the typically popular fish were missing their daily audience of human visitors.

What followed was a creative solution that captured hearts worldwide and taught us something special about these mysterious ocean giants.

1. The Problem: A Lonely Sunfish At Kaikyokan Aquarium

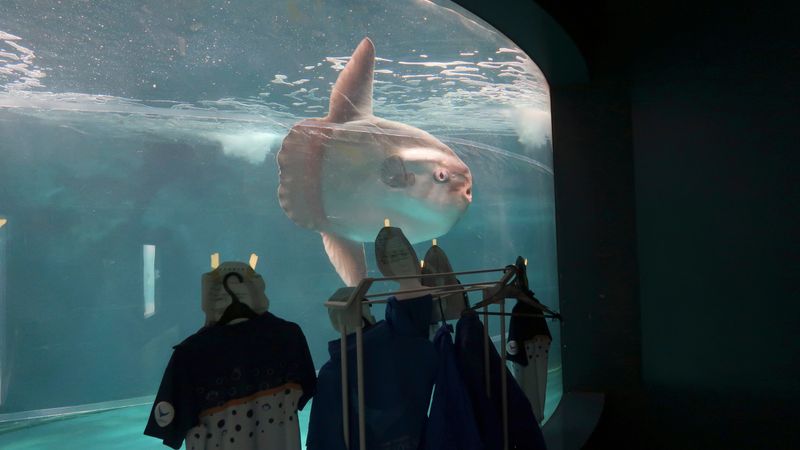

Staff at Kaikyokan aquarium in Japan noticed their normally active sunfish behaving strangely. The massive ocean dweller refused meals and spent hours rubbing against the glass walls of its tank.

Concern quickly spread among the caretakers as appetite loss in captive marine animals often signals health problems. The timing was particularly worrying – the aquarium had temporarily closed its doors for scheduled renovations.

Without the usual stream of fascinated visitors pressing their faces against the glass, something seemed off with their finned friend. The sunfish’s behavior presented a mystery that required quick thinking to solve.

2. Why The Sunfish Stopped Eating And Rubbed The Tank

Marine biologists at Kaikyokan observed the sunfish’s peculiar behavior with growing alarm. The fish repeatedly swam to the viewing glass, rubbing its body along the surface where visitors normally gathered.

Food refusal in captive sunfish can quickly become dangerous. These massive creatures need regular nutrition to maintain their unique physiology and impressive size.

The staff developed a theory – perhaps the sunfish missed human interaction? These ocean giants, despite their alien appearance, had shown surprising awareness of their surroundings. The sunfish’s tank-rubbing occurred precisely where visitors typically clustered, suggesting a connection between human presence and the fish’s well-being.

3. How The Aquarium’s Renovations Affected The Sunfish

Kaikyokan’s temporary closure for renovations created an unexpected challenge for their star ocean resident. The normally bustling viewing area fell silent, depriving the sunfish of its daily stimulation.

Aquarium environments carefully balance physical and psychological needs of marine life. The sudden absence of tapping fingers, excited faces, and the constant movement of visitors represented a dramatic change in the sunfish’s environment.

Construction noise and altered staff routines further disrupted the fish’s sense of normalcy. What seemed like simple building improvements to humans had inadvertently created a sensory desert for an animal accustomed to regular interaction through the glass barrier of its watery home.

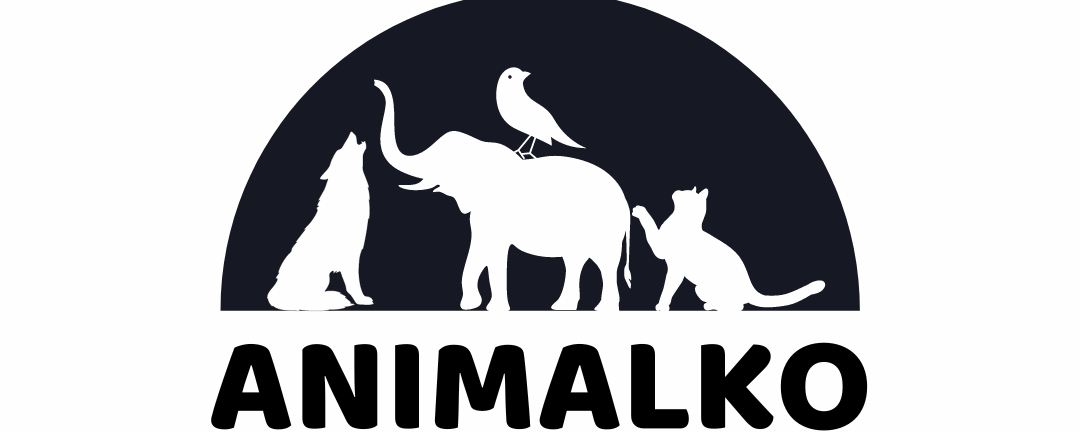

4. General Info: What You Need To Know About Sunfish

Sunfish (Mola mola) rank among the ocean’s most unusual creatures. These flat, disc-shaped giants can reach weights exceeding 2,000 pounds and lengths of 10 feet, making them the heaviest bony fish on Earth.

Despite their massive size, sunfish feed primarily on jellyfish and small fish. Their distinctive appearance features a truncated body that looks almost like half a fish with massive fins on top and bottom.

More social than previously thought, sunfish demonstrate awareness of their surroundings and can recognize feeding routines. They’re known to bask at the ocean’s surface, warming themselves after deep dives – a behavior that earned them their name as they appear to be “sunbathing.”

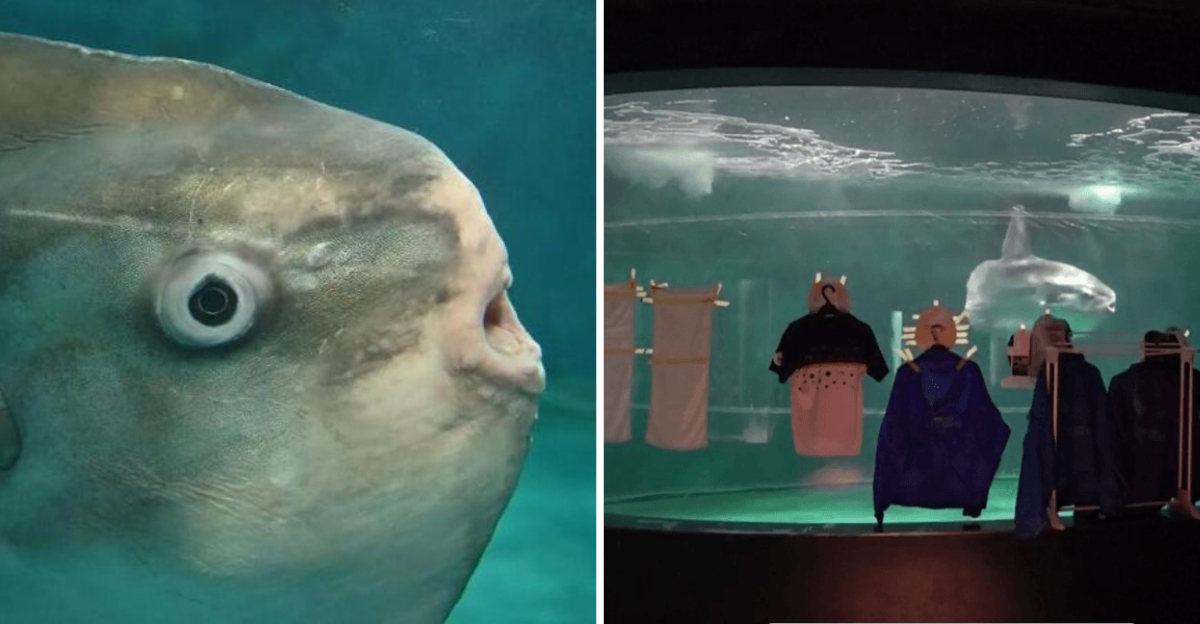

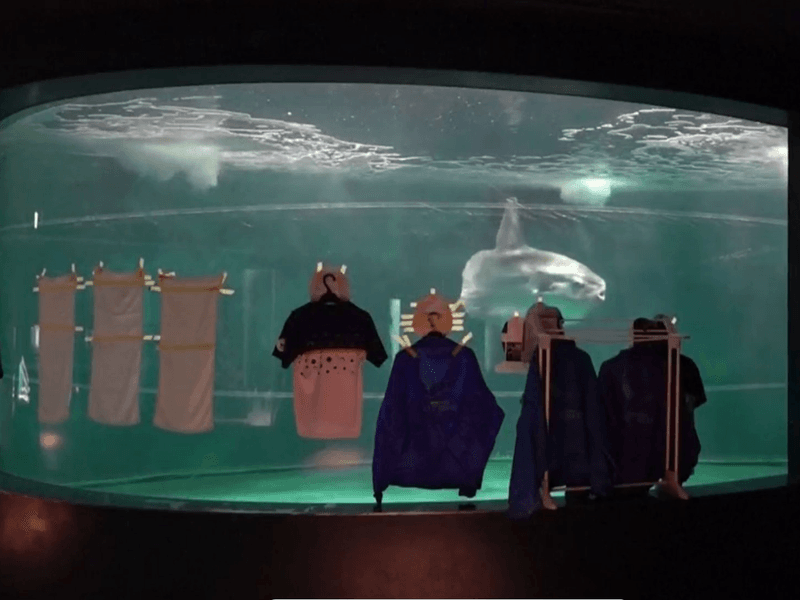

5. The Solution: Using Cardboard Face Cutouts To Simulate Visitors

Kaikyokan staff hatched an ingenious plan to comfort their distressed sunfish. They created life-sized cardboard cutouts of human faces and positioned them where visitors would normally stand.

The simple yet brilliant solution mimicked the silhouettes and shapes that would typically appear at the viewing glass. Caretakers carefully arranged these fake “spectators” at various heights to simulate groups of visitors.

Some cutouts featured smiling children, others showed adults with expressions of wonder – all designed to recreate the visual stimulation the sunfish had grown accustomed to. This low-tech approach represented a creative gamble that the fish might respond to familiar shapes rather than requiring actual human presence.

6. The Sunfish’s Reaction: Eating Again After The Cutouts

The effect of the cardboard audience was almost immediate. Within hours of installing the face cutouts, the sunfish approached the viewing glass with renewed interest.

Staff watched in amazement as their finned friend began swimming energetically near the fake visitors. Most importantly, when feeding time arrived, the sunfish readily accepted food for the first time in days.

The once-lethargic creature returned to its normal swimming patterns, occasionally pausing to “interact” with its cardboard companions. This remarkable turnaround confirmed the staff’s theory – their sunfish craved social stimulation, even if that stimulation came from inanimate paper faces propped against the glass.

7. Was Loneliness The Cause? Experts Share Their Thoughts

Marine biologists were fascinated by the Kaikyokan sunfish case. Several experts suggested the fish had indeed formed associations between human presence and positive experiences like feeding times.

Dr. Nakamura, a fish behavior specialist, explained that while “loneliness” might anthropomorphize the situation, the sunfish had clearly developed environmental expectations. The sudden absence of visual stimuli disrupted these patterns, causing stress responses.

Other scientists pointed to similar cases where captive marine animals showed awareness of human visitors. The sunfish’s reaction to cardboard substitutes demonstrated remarkable adaptability and suggested these ocean giants possess greater cognitive complexity than previously understood – recognizing shapes and associating them with comfort.

8. The Positive Outcome: Sunfish In Better Spirits

Following the cardboard visitor solution, the sunfish’s health improved dramatically. Its swimming patterns normalized, showing the graceful movements typical of these ocean giants.

Appetite returned with enthusiasm – the fish consumed its full diet daily, maintaining the nutrition needed for its massive frame. Staff noted increased activity during feeding demonstrations, suggesting the sunfish had regained its natural curiosity.

Blood tests confirmed reduced stress hormones, providing scientific evidence that the psychological intervention had physical benefits. The aquarium team continued refining their cutout display, occasionally changing the faces to provide variety. By the time renovations completed and real visitors returned, the sunfish had fully recovered from its temporary slump.

9. Media Attention: The Success Of The Cardboard Faces

News of the sunfish’s unusual therapy spread quickly across Japan and then worldwide. Major networks featured the story, charmed by both the fish’s apparent loneliness and the creative solution.

Social media exploded with shares and comments, many expressing surprise that a fish could form such connections with humans. The hashtag #LonelySunfish trended briefly, bringing unexpected attention to ocean conservation issues.

Kaikyokan’s innovative approach earned praise from animal welfare organizations for prioritizing psychological health alongside physical care. The aquarium created a special exhibit documenting the case, complete with the original cardboard cutouts that had saved their sunfish from its mysterious malaise.

10. Could Other Aquariums Use This Approach?

The Kaikyokan success story sparked conversations among aquarium professionals worldwide. Several facilities with sensitive species began experimenting with visual enrichment during necessary closures or maintenance periods.

Monterey Bay Aquarium implemented a similar approach with their sea otters during a brief closure, reporting positive behavioral outcomes. Research teams began formal studies to determine which species respond most strongly to human silhouettes versus actual interaction.

Experts caution that results likely vary by species and individual animal personality. The approach works best with creatures already habituated to human presence rather than newly captured specimens. Nevertheless, the simple cardboard solution offers an inexpensive, low-tech option worth trying when animal welfare concerns arise.

11. Lessons Learned: Creative Solutions For Animal Care

Kaikyokan’s experience highlighted the importance of thinking beyond physical needs when caring for complex marine life. The simplest solution – cardboard cutouts – proved more effective than expensive medical interventions or supplements.

The aquarium now includes psychological enrichment as a standard part of animal care protocols. Staff training emphasizes observation of subtle behavioral changes that might indicate mental rather than physical distress.

Perhaps most importantly, the sunfish case shattered preconceptions about fish cognition and awareness. These animals, often dismissed as having “three-second memories,” clearly form environmental associations and expectations. The experience has fostered greater respect for the emotional lives of all aquarium residents, from the smallest damselfish to the mightiest sharks.

12. The Importance Of Social Interaction For Marine Animals

The sunfish case added to growing evidence that many marine species are far more socially complex than previously believed. Research now suggests that regular stimulation – whether from conspecifics or other species – plays a crucial role in captive animal welfare.

Dolphins and whales have long been recognized as social creatures, but similar needs exist across many species. Even seemingly solitary animals often engage with their environment in ways that include awareness of other organisms.

For aquariums worldwide, this means rethinking exhibit design to balance viewing opportunities with animal needs. Kaikyokan now schedules “quiet days” with limited visitors, alternating with normal operations to provide varied stimulation levels. Their sunfish, once lonely, has become an ambassador for understanding the hidden emotional lives of ocean dwellers.