15 Extinct Snakes That Could Have Changed The Evolution Of Reptiles

Imagine a world where giant sea serpents ruled the oceans and massive constrictors dominated ancient forests.

Extinct snakes have left gaps in our understanding of reptile evolution that scientists are still trying to piece together. These mysterious serpents, now only known through fossils, might have completely changed how reptiles evolved if they had survived to influence modern species.

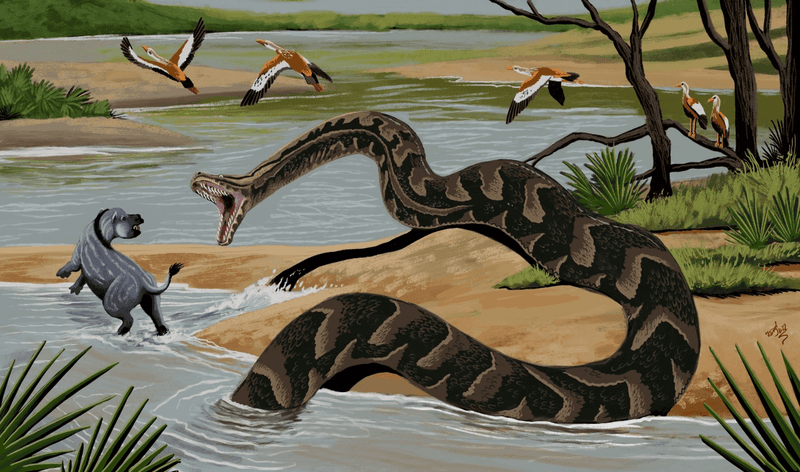

1. Titanoboa

Weighing as much as a school bus, this colossal predator ruled the rainforests of Colombia 60 million years ago. Fossils suggest it could crush prey with the force of 400 pounds per square inch.

Scientists believe Titanoboa’s massive size evolved due to the extremely warm climate of prehistoric Earth, challenging our understanding of how reptiles respond to temperature changes.

2. Madtsoia

Before pythons or boas dominated the constrictor scene, Madtsoia squeezed prey across South America, Africa, and even Antarctica when it was still warm. Its fossils reveal a snake that could grow up to 33 feet long.

Had this prehistoric giant survived, modern constrictors might look completely different today, as Madtsoia’s unique jaw structure suggests it had feeding adaptations unlike any modern snake.

3. Najash

Found in Argentina’s Patagonia region, Najash rionegrina upended everything we thought we knew about snake evolution. Unlike most fossil snakes, it retained functional hind legs, proving snakes didn’t evolve from marine ancestors as previously thought.

Had this transitional species survived, we might have seen an entire branch of legged serpents developing alongside their legless cousins.

4. Pachyrhachis

Talk about an identity crisis! Pachyrhachis problematicus got its name because it confused scientists for decades. Discovered in Israel, this 95-million-year-old marine snake had a paddle-like tail and tiny hind limbs.

Its mixture of lizard and snake features might have represented a completely different evolutionary path for serpents if its lineage had continued, potentially creating an entire branch of sea-dwelling snakes.

5. Gigantophis

Before Titanoboa stole the spotlight, Gigantophis garstini held the title of world’s largest snake. Roaming ancient Egypt and Algeria 40 million years ago, this 33-foot behemoth hunted early elephant ancestors.

Its massive vertebrae show a different growth pattern than modern constrictors. Had it survived, Gigantophis might have given rise to super-sized African snakes unlike anything alive today.

6. Dinilysia

Looking more like a snake’s great-grandfather than its cousin, Dinilysia patagonica lived 85 million years ago in Argentina. Its skull shows features halfway between lizards and modern snakes, including a unique jaw structure.

As one of the most primitive true snakes ever found, its survival could have created entirely different feeding adaptations in modern serpents, potentially changing predator-prey relationships worldwide.

7. Eupodophis

Frozen in evolutionary time, Eupodophis descouensi from Lebanon shows us exactly what snakes looked like as they lost their limbs. Unlike other primitive snakes, its single hind leg appears completely functional.

Had this 90-million-year-old marine species survived, we might today see snakes with varying degrees of limb development. Its fossils are so well-preserved that scientists can even see scales!

8. Wonambi

Named after a mythical Rainbow Serpent from Aboriginal lore, Wonambi naracoortensis ambushed prey at waterholes across ancient Australia until just 40,000 years ago. Unlike modern constrictors, its skull suggests it swallowed prey whole without constricting first.

Aboriginal Australians may have actually encountered these 18-foot predators, possibly explaining why snake legends feature so prominently in their mythology.

9. Yurlunggur

Imagine a blind snake the size of a anaconda! Yurlunggur camfieldensis was exactly that – a 20-foot relative of today’s tiny blind snakes that hunted in Australia’s Northern Territory 23 million years ago.

Its survival would have completely rewritten what we know about blind snake evolution. Instead of remaining small and specialized, blind snakes might have become apex predators in certain ecosystems.

10. Archaeophis

Gliding through warm oceans 50 million years ago, Archaeophis proavus had over 500 vertebrae – more than any snake alive today. This incredible flexibility made it perfect for marine life in ancient European seas.

Its extremely elongated body represents an evolutionary experiment that didn’t survive. Had it persisted, modern sea snakes might have developed even more extreme adaptations for ocean dwelling.

11. Sanajeh

Caught in the act! Sanajeh indicus was fossilized next to a nest of titanosaur dinosaur eggs, one containing a baby dinosaur. This 3.5-foot predator from India specialized in raiding dinosaur nests 67 million years ago.

Its unique jaw wasn’t expandable like modern snakes, showing a completely different feeding adaptation. Had it survived the asteroid impact, Sanajeh might have evolved to target bird nests instead.

12. Haasiophis

Sporting tiny hind limbs and a flattened paddle-tail, Haasiophis terrasanctus shows how snakes experimented with marine life 95 million years ago. Discovered in Israel, this 3-foot hunter had a unique swimming style unlike any modern snake.

Its body shape suggests it was highly specialized for certain marine environments. If its lineage had continued, we might have seen incredible diversity in sea snake locomotion styles.

13. Coniophis

Meet the snake that started it all! Coniophis precedens lived 70 million years ago and represents the most primitive snake ever discovered. Unlike later snakes, it still had a lizard-like head but a snake-like body.

Scientists believe it lived underground and couldn’t eat large prey. If this evolutionary experiment had diversified differently, modern snakes might have retained more lizard-like features instead of their specialized skulls.

14. Simoliophis

Half-snake, half-lizard, all predator! Simoliophis rochebrunei hunted along coastal waters of ancient Africa and Europe 95 million years ago. Its body shows a fascinating mix of aquatic and terrestrial adaptations.

With specialized vertebrae that were neither fully land nor fully sea-adapted, it represents a completely different approach to coastal living than any modern snake. Its extinction left a gap in shoreline ecosystems.

15. Diablophis

Found in Colorado, Diablophis gilmorei represents one of the earliest known burrowing snakes from 155 million years ago. Despite living alongside dinosaurs, it already showed specialized adaptations for life underground.

Its small size and reinforced skull suggest it dug through soil much like modern blind snakes. Had this Jurassic innovator survived, underground snake diversity might be completely different today.