15 Extinct Bird Species The World Will Never See Again

Birds have captivated humans with their beautiful colors, enchanting songs, and remarkable abilities to soar through the skies.

But sadly, many incredible bird species have vanished forever due to human activities, habitat destruction, and introduced predators. These extinct birds represent not just lost beauty, but important chapters in Earth’s evolutionary story that we can never fully recover.

1. Passenger Pigeon: From Billions To None

Once darkening North American skies in flocks so vast they took days to pass overhead, Passenger Pigeons numbered in the billions—possibly the most abundant bird species ever. Their reddish breasts and long, pointed tails flashed as they migrated in spectacular numbers.

Commercial hunting in the 19th century decimated them with shocking speed. Martha, the last of her kind, died in Cincinnati Zoo on September 1, 1914.

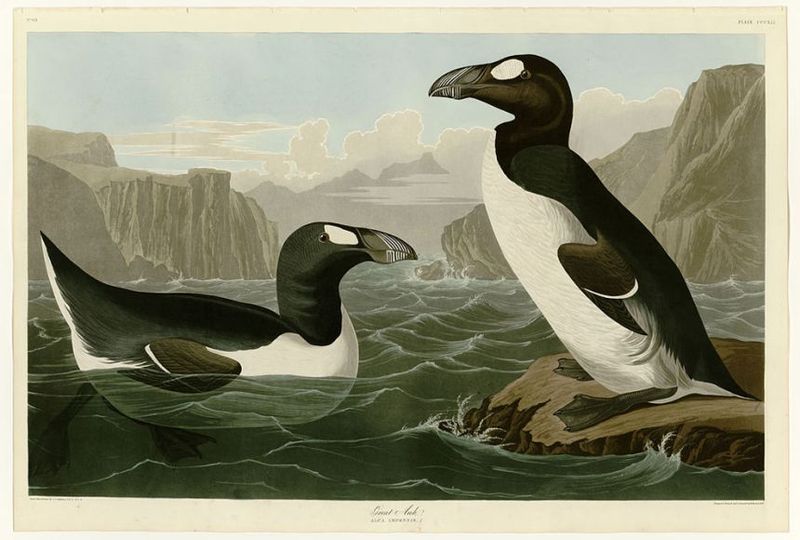

2. Great Auk: The Original Penguin

Resembling penguins but unrelated, Great Auks were flightless seabirds standing three feet tall with tuxedo-like black and white plumage. These powerful swimmers once populated rocky islands across the North Atlantic.

Hunted mercilessly for their meat, eggs, and feathers, the last confirmed pair was killed in 1844 on an Icelandic island. Collectors frantically sought the remaining birds, accelerating their extinction as specimens became more valuable.

3. Carolina Parakeet: America’s Lost Parrot

Bright green bodies with yellow heads and orange faces made Carolina Parakeets unmistakable as they chattered through eastern American forests. These social birds were the only native parrot species in the eastern United States.

Farmers shot them as agricultural pests, while milliners coveted their colorful feathers for ladies’ hats. Incapable of fearing danger, they would circle back when flock members were shot. The last captive bird died at Cincinnati Zoo in 1918.

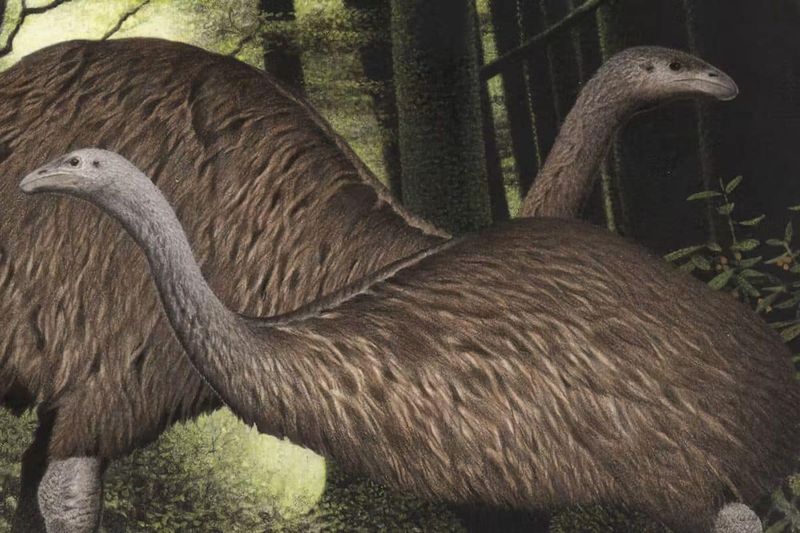

4. Moa: New Zealand’s Giant Wonder

Imagine encountering a bird taller than a basketball player! The largest Moa species reached 12 feet high, with long necks stretching toward tree canopies. These flightless giants evolved in New Zealand’s predator-free environment.

When Māori settlers arrived around 1300 CE, they found perfect hunting targets—enormous birds with no fear of humans. Within just 100 years, all nine Moa species disappeared, representing one of history’s swiftest extinction events.

5. Huia: The Sacred Bird With Mismatched Bills

Among nature’s most remarkable adaptations, Huia birds featured dramatically different beaks between sexes. Males had short, straight bills for hammering wood, while females possessed long, curved bills perfect for extracting grubs from deep within trees.

Sacred to New Zealand’s Māori people, these black birds with white-tipped tails became fashion victims when European royalty popularized their tail feathers as hat decorations. The last confirmed sighting came in 1907.

6. Elephant Bird: Madagascar’s Feathered Giant

Standing nearly 10 feet tall and weighing half a ton, Elephant Birds produced eggs bigger than dinosaur eggs—the largest ever laid by any vertebrate. These Madagascan behemoths couldn’t fly but could easily outrun humans.

Arab sailors wrote about these birds in the 10th century, but human settlement, habitat loss, and egg collection drove them to extinction by the 17th century. Their massive, football-sized eggs remain prized museum specimens today.

7. Laughing Owl: New Zealand’s Vanished Voice

The night forests of New Zealand once echoed with calls described as “a series of dismal shrieks, often compared to the mad yelling of a dog.” These distinctive vocalizations gave the Laughing Owl its memorable name.

Medium-sized with speckled brown plumage, these ground-nesters became easy targets for introduced rats and stoats. European settlement brought both predators and habitat destruction. By 1914, their eerie laughter had fallen silent forever.

8. Stephen’s Island Wren: Found And Lost In One Stroke

Lighthouse keeper David Lyall’s cat made a bizarre scientific contribution in 1894—bringing home specimens of a previously undiscovered bird species. This tiny, flightless wren existed only on Stephen’s Island, a small outcrop in New Zealand’s Cook Strait.

In a tragic twist, the same cat that helped discover the species contributed to its extinction. Within a year of its scientific identification, the Stephen’s Island Wren disappeared completely—one of history’s most rapid documented extinctions.

9. Heath Hen: America’s Lost Prairie Chicken

Once abundant along the Eastern seaboard from Maine to Virginia, Heath Hens provided sustenance for both Native Americans and early colonists. These chicken-sized birds with barred plumage performed elaborate mating dances each spring, inflating orange air sacs on their necks.

Overhunting pushed them to Martha’s Vineyard by 1870. Despite establishing America’s first wildlife refuge to protect them in 1908, a perfect storm of fire, disease, predation, and inbreeding sealed their fate by 1932.

10. Labrador Duck: The Mystery Bird Of North America

Among North America’s first recorded bird extinctions, the Labrador Duck vanished so quickly that scientists barely understood its life history. With distinctive black-and-white plumage and an unusual soft bill specialized for mollusk feeding, these sea ducks remained mysterious.

Never abundant, they disappeared from Atlantic coastal waters by 1878. While hunting likely contributed to their decline, scientists suspect their specialized diet made them particularly vulnerable to shoreline development and shellfish harvesting along migration routes.

11. Bachman’s Warbler: The Silent Southern Songbird

Once filling southern swamps with melodious songs, Bachman’s Warblers were tiny yellow birds with distinctive black throats and foreheads. These neotropical migrants wintered in Cuba but bred exclusively in southeastern U.S. bottomland forests.

Their specialized habitat needs made them vulnerable when swamplands were drained for agriculture. Hurricane damage to Cuban wintering grounds further stressed the population. Though the last confirmed sighting came in 1988, they were likely gone decades earlier.

12. Ivory-billed Woodpecker: The Lord God Bird

So magnificent that observers would exclaim “Lord God, what a bird!” upon spotting one, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker was North America’s largest woodpecker. With a striking red crest, tuxedo-like plumage, and ivory-colored bill, it required vast old-growth forests to survive.

Extensive logging of southern bottomland forests destroyed its habitat. Though officially declared extinct in 2021, persistent unconfirmed sightings fuel hope among optimistic birders that a few might still survive in remote swamplands.

13. Paradise Parrot: Australia’s Colorful Casualty

Arguably Australia’s most beautiful bird, the Paradise Parrot displayed a rainbow of colors—emerald back, scarlet breast, turquoise cheeks, and a long pointed tail. These ground-nesters thrived in grassy woodlands of Queensland and northern New South Wales.

European settlement brought cattle grazing that destroyed nesting habitat, while introduced foxes and cats preyed on eggs and young. Despite conservation efforts beginning in the 1920s, the last confirmed sighting came in 1927, making it Australia’s only mainland parrot to disappear.

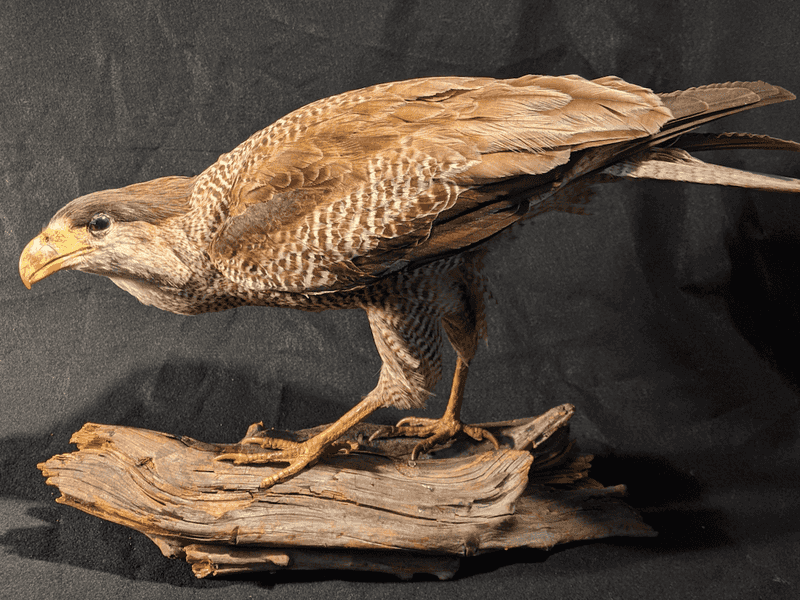

14. Guadalupe Caracara

The Guadalupe Caracara was a powerful bird of prey endemic to the arid landscapes of Guadalupe Island. Known for its fierce hunting skills and striking appearance, it was often misunderstood by early settlers.

This bird faced relentless persecution by humans who mistakenly believed it posed a threat to livestock. Despite not being a direct threat, it was hunted to extinction in the late 19th century.

15. Dodo Bird: The Poster Child Of Extinction

The flightless Dodo vanished from Mauritius in the late 17th century, barely 80 years after Europeans discovered it. Sailors hunted these trusting birds relentlessly, while introduced rats, pigs, and monkeys devoured their eggs.

Standing three feet tall with a distinctive hooked beak, the Dodo couldn’t adapt to these new threats. Its name now symbolizes extinction itself—a tragic reminder of humanity’s destructive impact.