Scientists Once Thought Dinosaurs Roared, But They May Have Actually Been Silent

When you picture a dinosaur, you probably hear that terrifying roar from Jurassic Park in your head. For decades, we’ve imagined these prehistoric creatures making earth-shaking sounds that matched their massive size.

But recent scientific discoveries suggest something surprising – dinosaurs might have been much quieter than we thought. The truth about dinosaur sounds could change everything we thought we knew about these fascinating animals.

Where The Roar Idea Came From

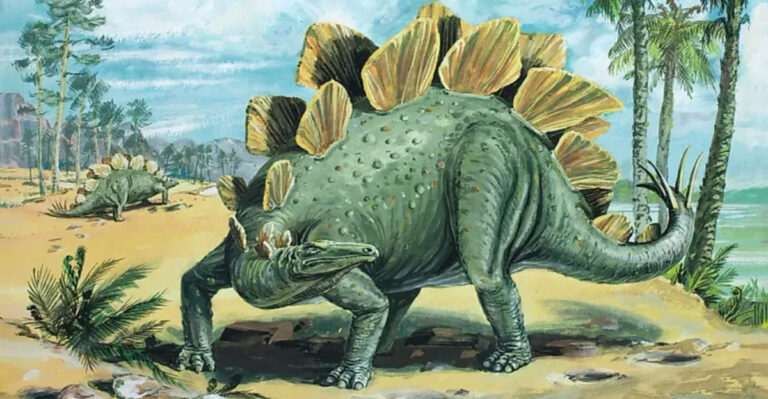

Our belief that dinosaurs roared began with Victorian-era paleontologists who first reconstructed these massive skeletons. Looking at creatures so enormous, scientists naturally assumed they must have produced sounds to match their size.

Early dinosaur experts compared them to modern crocodiles and lions – animals known for their powerful vocalizations. This association stuck in scientific thinking for over a century.

Without actual sound recordings from millions of years ago, these assumptions went unchallenged. The roaring dinosaur became cemented in our collective imagination, reinforced by books, museum displays, and later, movies that needed dramatic sound effects for these prehistoric giants.

Dinosaurs And Hollywood Sound Effects

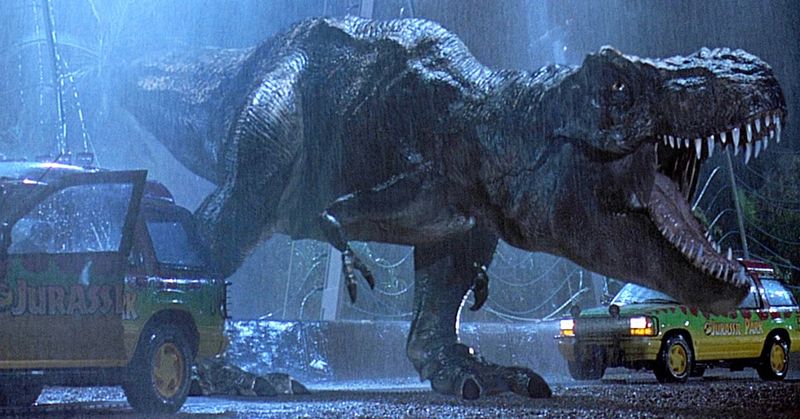

Movie magic created the dinosaur roars we all recognize today. Sound designers for Jurassic Park famously combined recordings of elephants, alligators, and tigers to craft the T-Rex’s iconic bellow. These artificial sounds had no scientific basis – they just sounded scary!

Hollywood needed dramatic audio to match the visual impact of these creatures on screen. The roars became so ingrained in pop culture that most people never questioned their accuracy.

Film sound designers weren’t trying to be scientifically accurate – they were creating entertainment. Yet these creative choices shaped public perception more powerfully than any scientific paper could, establishing what we “know” dinosaurs sounded like despite having zero evidence.

What Modern Science Says About Dinosaur Vocal Cords

Recent anatomical studies reveal a surprising truth: dinosaurs likely lacked the vocal cord structure needed for roaring. Scientists examining fossilized throat regions found no evidence of a larynx similar to mammals that roar.

Instead, dinosaurs probably had anatomy more like modern birds – their closest living relatives. Birds use a syrinx for vocalizing, not a larynx, and this structure rarely preserves in fossils.

Without the physical equipment for roaring, dinosaurs physically couldn’t produce those movie-famous sounds. The biological evidence suggests they might have made closed-mouth vocalizations, hisses, booms, or coos – but nothing resembling the theatrical roars we’ve come to expect from these prehistoric creatures.

The Birds And Reptiles Clue

Modern birds – direct descendants of dinosaurs – offer our best clues about dinosaur sounds. From the gentle cooing of doves to the rhythmic hoots of owls, birds make diverse sounds without roaring. Even cassowaries, the most dinosaur-like modern birds, produce deep booming sounds rather than roars.

Living reptiles provide additional insights. Alligators and crocodiles, while capable of hissing and bellowing, don’t produce true roars either. They make these sounds with closed mouths, pushing air through their bodies.

By studying these living relatives, paleontologists now believe dinosaurs likely produced a range of sounds – from low-frequency rumbles to hisses and perhaps bird-like calls – but traditional roars were probably not in their vocal repertoire.

Why Roaring Might Not Have Been Practical

Roaring serves specific purposes for modern animals – primarily intimidation and territory marking. For many dinosaur species, especially the largest ones, such noisy displays might have been unnecessary or even counterproductive.

Super-sized dinosaurs like Brachiosaurus already dominated by sheer size. They didn’t need loud vocalizations to appear threatening – just being visible was enough!

Predators like Velociraptor likely hunted using stealth tactics. Making loud roars would have announced their presence to prey, ruining their hunting advantage. From an evolutionary perspective, many dinosaurs may have benefited more from quieter communication methods that didn’t broadcast their location to predators or prey across the ancient landscapes.

Other Ways Dinosaurs Could Have Communicated

Dinosaurs likely relied on visual displays for communication – much like modern birds with their colorful feathers and elaborate dances. The elaborate crests, frills, and horns of many dinosaur species may have been primarily for visual signaling rather than combat.

Stomping and ground vibrations could have sent messages across great distances. Elephants use similar low-frequency communication that travels through the ground, allowing herds to coordinate over miles.

Scent marking might have played a crucial role too. Many dinosaurs had large olfactory lobes in their brains, suggesting a keen sense of smell. Chemical signals could have conveyed complex information about territory, mating readiness, and identity without making a sound.

Whispers Grunts And Low-Frequency Sounds

Paleontologists now suspect dinosaurs communicated through a variety of subtle sounds undetectable to human ears. Infrasound – extremely low-frequency vibrations below human hearing range – could have traveled miles across prehistoric landscapes, allowing dinosaurs to communicate over vast distances.

Closed-mouth vocalizations similar to an alligator’s rumble might have been common. These sounds generate through resonance chambers in the throat without requiring mammalian vocal cords.

Some dinosaur species had hollow crests that likely functioned as resonating chambers. Parasaurolophus, with its tube-shaped head crest, may have produced haunting, trumpet-like calls rather than roars. These specialized structures suggest dinosaurs evolved sophisticated sound-making abilities quite different from the simple roars we’ve imagined.

Could Dinosaurs Have Used Body Language Instead?

The elaborate physical features of many dinosaurs suggest body language played a crucial role in their communication. Triceratops’ massive frills likely served as visual displays for attracting mates or intimidating rivals – no sound required.

Tail positioning, head bobbing, and physical postures could convey complex messages. Modern birds use intricate body movements to communicate everything from danger warnings to mating readiness.

Some dinosaurs may have had colorful features we’ll never know about from fossils alone. Feathers, skin flaps, and inflatable throat pouches could have created dramatic visual signals. The discovery of melanin in some dinosaur fossils confirms they had colored bodies, suggesting visual communication was highly developed – potentially reducing their need for loud vocalizations.

What Fossil Evidence Can And Can’t Tell Us

Fossils preserve bones but rarely capture soft tissues like vocal organs. This fundamental limitation means we may never know with absolute certainty what dinosaurs sounded like. The best evidence comes from studying skull structures and air passages that might have contributed to sound production.

CT scans of dinosaur skulls reveal brain case details that hint at hearing capabilities. Some species had excellent hearing in specific frequency ranges, suggesting they produced sounds in those same ranges.

Computer modeling now allows scientists to recreate possible dinosaur sounds based on anatomical evidence. By analyzing the resonance chambers in well-preserved skulls, researchers have simulated what some dinosaurs might have sounded like – and roars aren’t on the playlist. These models suggest honks, booms, and low-frequency rumbles were more likely.

The Quiet Giants Of Prehistoric Earth

Imagine a world where massive dinosaurs moved through ancient forests and plains in relative silence. Rather than the chaos of constant roaring we see in movies, dinosaur communication might have been surprisingly subtle and efficient.

The largest dinosaurs likely produced infrasound rumbles that traveled for miles without being particularly loud at the source – similar to how elephants communicate today. These vibrations might have felt more like distant thunder than aggressive roars.

This revised understanding doesn’t make dinosaurs any less impressive. In fact, it paints a picture of sophisticated creatures using energy-efficient communication perfectly adapted to their needs. The real dinosaurs – communicating through body language, visual displays, and subtle sounds – were perhaps more fascinating than their Hollywood counterparts.