12 Animals That Were Essential To Pioneers’ Survival In Early America

When pioneers ventured into the untamed wilderness of early America, they relied on certain animals for their very survival. These creatures provided food, transportation, protection, and materials that made life possible in harsh frontier conditions.

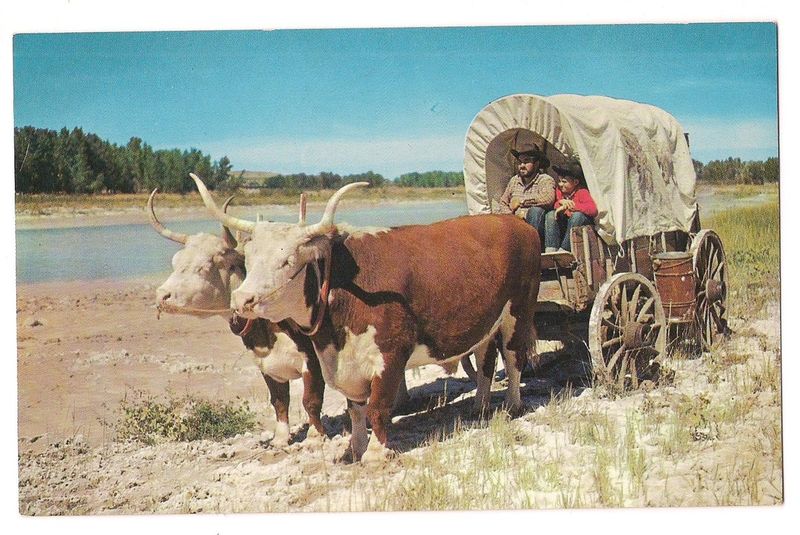

From the hearty oxen pulling covered wagons across treacherous terrain to the humble honeybee producing liquid gold, these animals were the unsung heroes of America’s westward expansion.

1. Oxen: The Muscle Behind The Wagon Trains

Lumbering giants with unmatched endurance, oxen were the powerhouses that pulled pioneer wagons across thousands of miles of rugged terrain. Unlike horses, these sturdy beasts could survive on poor-quality grasses found along the trail and required less water during long journeys.

A single team of oxen could haul a fully loaded wagon weighing over 2,000 pounds for 10-12 miles per day. Their slow but steady pace – typically about two miles per hour – matched the walking speed of pioneers who often traveled on foot alongside their wagons.

Most wagon trains used multiple yokes of oxen, with experienced trail captains preferring these reliable animals over the faster but more temperamental horses for the grueling journey westward.

2. Horses: Swift Messengers And Loyal Companions

Galloping across vast prairies and navigating dense forests, horses served as the pioneers’ vital connection to distant settlements. A good horse could cover 20-30 miles in a day, making them essential for carrying messages, scouting new territories, or fetching a doctor during emergencies.

Beyond transportation, horses worked tirelessly alongside their human partners to plow fields and haul harvests. Many pioneer families formed deep bonds with these intelligent animals, often naming them and considering them part of the family.

Some Native American tribes traded prized horses to settlers, creating important cultural and economic connections between different peoples on the frontier. These exchanges sometimes led to peaceful relationships that benefited both communities.

3. Pigs: The Ultimate Homestead Survivors

Hardy and resourceful, pigs thrived in frontier conditions where other livestock might struggle. Pioneers valued these animals for their remarkable ability to convert kitchen scraps, forest nuts, and almost anything edible into valuable protein with minimal oversight.

A single sow could produce two litters annually, with each containing 6-12 piglets. This rapid reproduction rate meant a small starter herd could quickly grow to feed an entire family for years. Fall butchering became a community event on the frontier, with neighbors gathering to help process the meat.

Every part of the pig found purpose – meat became bacon, ham and sausage; fat rendered into essential cooking lard and soap; even bladders were dried and used as containers. The saying “using everything but the squeal” wasn’t just clever – it was survival.

4. Cattle: Walking Larders Of The Frontier

Fresh milk sloshing in wooden buckets was a precious commodity for pioneer families pushing westward. A single dairy cow could produce enough milk to feed a family, with plenty left over for making butter and cheese that would keep through harsh winters.

Cattle drives became legendary aspects of frontier life, with cowboys moving vast herds across unfenced territories to reach distant markets. These epic journeys could span hundreds of miles and take months to complete, facing dangers from stampedes to river crossings.

Beyond dairy, cattle provided essential beef, leather for shoes and harnesses, and tallow for candles. Oxen were actually cattle too – specifically, castrated male cattle trained as draft animals – showing how versatile these animals were to frontier survival.

5. Chickens: The Breakfast Providers

Clucking contentedly around pioneer homesteads, chickens delivered protein-rich eggs daily with minimal investment. A small flock could produce 1,000-1,500 eggs annually – a reliable food source that required little land or care compared to larger livestock.

Pioneer women often managed the chicken flock, collecting eggs daily and monitoring hens for broodiness. When a hen went broody (showed nesting behavior), she’d be given a clutch of fertilized eggs to hatch, ensuring the flock’s continuation without purchasing new birds.

Beyond eggs, chickens provided meat for special occasions and feathers for stuffing pillows and mattresses.

Their natural scratching behavior helped control insects around the homestead, and their droppings enriched garden soil – making them truly multi-purpose animals for frontier families.

6. Dogs: Guardians Of The Homestead

Alert to every unfamiliar sound, frontier dogs served as living alarm systems when danger approached isolated homesteads. Their sensitive ears could detect predators or strangers long before humans, giving families precious time to prepare for whatever might be coming.

Working alongside their owners, these loyal animals helped herd livestock, protected children, and assisted in hunting game. Many pioneer journals mention beloved dogs by name, showing the deep bonds formed between families and their canine companions during difficult times.

Breeds varied widely across the frontier, with some families bringing established working breeds while others adopted mixed-breed dogs with natural survival instincts.

Regardless of pedigree, a good dog was worth its weight in gold on the frontier – a faithful friend who asked little but gave everything.

7. Honeybees: Sweet Reward For Frontier Beekeepers

Buzzing between wildflowers across newly settled lands, honeybees transformed frontier gardens into productive food sources. European settlers brought hives with them, recognizing these industrious insects as essential partners in agriculture and food production.

Honey served as the primary sweetener for pioneer families before processed sugar became widely available. A single healthy hive could produce 60-80 pounds of honey annually – enough to sweeten foods throughout the year and provide a valuable trade commodity.

Beyond sweetness, bees provided beeswax for candle-making and waterproofing, while their pollination services dramatically increased fruit and vegetable yields.

Some pioneers practiced “bee hunting” – tracking wild bees to discover natural hives in hollow trees, then harvesting honey or capturing swarms to start managed colonies.

8. Sheep: The Walking Wardrobe

Grazing contentedly on rocky hillsides too steep for crops, sheep converted otherwise unusable land into valuable wool, meat, and milk. A small flock could clothe an entire family through the frontier’s harsh winters, with each animal producing 5-10 pounds of wool annually.

Spring shearing became a social event for isolated communities, with neighbors gathering to help each other harvest the precious fiber. After washing, carding, spinning, and weaving, this wool became everything from warm blankets to sturdy clothing – all produced within the homestead.

Merino sheep were particularly prized for their fine, soft wool, while heartier breeds like Cotswold and Lincoln produced longer fibers ideal for outerwear.

For many pioneer women, the rhythmic click of knitting needles by firelight became the soundtrack of winter evenings, transforming raw wool into family necessities.

9. Goats: The Frontier’s Dairy Dynamos

Scrambling up rocky terrain that would defeat other livestock, goats thrived in challenging landscapes where pioneers first settled. These adaptable animals could survive on browse that cattle would reject, making them perfect for families establishing homesteads on marginal land.

A good dairy goat produced 1-2 quarts of milk daily – enough for a family’s basic needs while requiring less feed than a cow. The naturally homogenized milk was easily digestible, making it valuable for infants and children when cow’s milk wasn’t available.

Beyond milk, goats provided meat, hides for leather, and fiber from certain breeds. Their natural curiosity and intelligence made them entertaining companions on isolated homesteads, though pioneers quickly learned to build secure fences – few animals rivaled a determined goat’s escape artistry!

10. Wild Game: Nature’s Grocery Store

Venison sizzling over an open fire represented survival for many pioneer families pushing into untamed territories. Hunting wasn’t sport – it was necessity, with deer, elk, bison, and smaller game providing critical protein when domestic meat wasn’t available.

Skilled hunters learned tracking methods from Native Americans and developed intimate knowledge of animal habits and habitats. A single deer could yield 40-60 pounds of meat that, when properly smoked or dried, would feed a family for weeks.

Nothing went to waste – hides became clothing and shelter, sinew served as strong natural thread, bones became tools and needles. Even the brains had purpose, used in a process called “brain tanning” to create soft, waterproof leather.

For pioneers living on the edge of wilderness, these wild animals meant the difference between survival and starvation.

11. Rabbits: The Homesteader’s Fast Food

Multiplying rapidly in hutches beside pioneer cabins, domestic rabbits provided a quick source of meat with minimal investment. A single doe could produce up to 30 kits (baby rabbits) annually, with each reaching butchering size in just 8-12 weeks – far faster than larger livestock.

These efficient converters transformed garden scraps and foraged greens into protein-rich meat that many compared to chicken. Their small size made them perfect for immediate consumption without preservation concerns that came with larger animals.

Beyond meat, rabbit pelts became warm linings for mittens and hats, while their droppings served as ready-made fertilizer for garden plots. Wild rabbits supplemented domestic stocks, with snares and traps providing additional meat for pioneer tables throughout the frontier territories.

12. Mules: The Frontier’s Four-Legged Problem Solvers

Combining the strength of horses with the surefootedness of donkeys, mules conquered terrain that would defeat other draft animals. These hybrid creatures inherited the best traits of both parents – intelligence, endurance, and an ability to thrive on poor forage while working tirelessly.

Miners and mountain settlers particularly valued mules for navigating narrow, treacherous paths while carrying heavy loads. A good pack mule could safely transport 150-200 pounds of supplies through conditions that would break wagons or exhaust horses.

Despite their reputation for stubbornness, experienced pioneers recognized this trait as self-preservation intelligence. A mule that refused to cross a bridge or ford a river was often detecting dangers invisible to human eyes – saving both itself and its handler from potential disaster.