Facts About Unique Hirola Antelopes And Why They’re On The Verge Of Disappearing

The Hirola antelope is one of the most endangered mammals on our planet. Found only in a small region between Kenya and Somalia, these elegant creatures have been quietly disappearing from our world.

Their population has crashed by more than 95% in recent decades, making them critically endangered and urgently in need of conservation efforts.

Scientific Classification And Unique Status

Standing alone in evolutionary history, the Hirola represents the last member of the genus Beatragus. This makes them incredibly valuable to science and biodiversity.

When a species is the final representative of its entire genus, its loss would erase millions of years of unique evolutionary development. Scientists call the Hirola a ‘living fossil’ for this reason.

Distinctive Physical Features

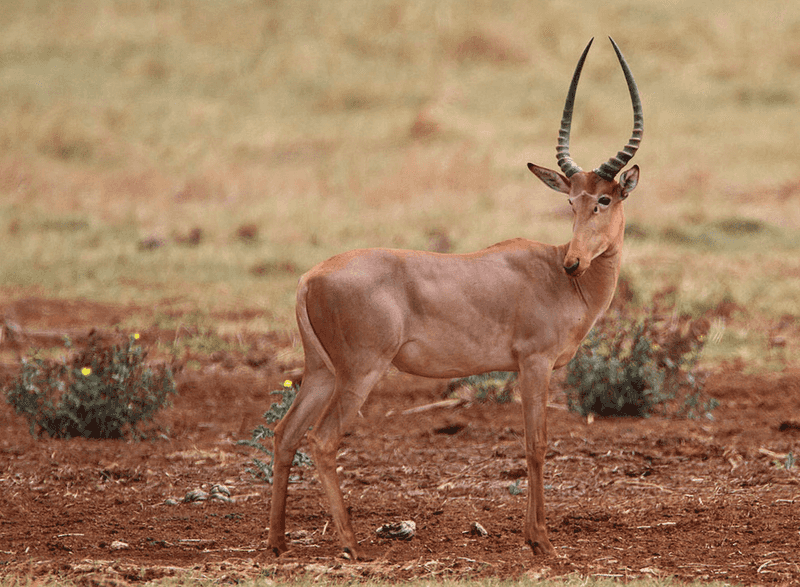

Nicknamed the ‘four-eyed antelope,’ Hirolas possess prominent preorbital glands beneath each eye that secrete a dark, sticky substance. These glands appear as a second set of eyes from a distance.

Their elegant lyre-shaped horns curve backward then forward, creating a distinctive profile. Their tawny coat transitions to white on their belly and tail, helping them blend into golden savanna grasses.

Habitat And Distribution

Once roaming widely across northeastern Kenya and southern Somalia, Hirolas now cling to existence in a tiny fragment of their former range. Their current wild habitat spans just 1,500 square kilometers along the Kenya-Somalia border.

A small sanctuary population was established in Tsavo East National Park as insurance against extinction in their native range.

Population Decline

From a thriving population of approximately 15,000 in the 1970s, fewer than 500 Hirolas remain today. This catastrophic 95% decline makes them among the most endangered mammals on Earth.

Without intervention, scientists predict they could vanish completely within the next decade. Each lost Hirola represents another step toward the extinction of this ancient lineage.

Impact Of Rinderpest Epidemic

The devastating rinderpest outbreak of the 1980s wiped out nearly 90% of all Hirolas in just a few years. This cattle disease spread rapidly through wild ungulate populations with devastating efficiency.

While rinderpest has since been globally eradicated, the Hirola population never recovered from this catastrophic blow. Their small numbers left them vulnerable to other threats.

Habitat Loss Due To Bush Encroachment

Open grasslands vital for Hirola survival have shrunk dramatically as woody vegetation takes over. Tree cover has expanded by over 250% in three decades, transforming their habitat.

Hirolas evolved as grazers needing clear sightlines to spot predators. Dense bushland prevents them from feeding efficiently and increases predation risk. Climate change accelerates this vegetation shift.

Competition With Livestock

Expanding herds of cattle, goats, and sheep directly compete with Hirolas for scarce grazing resources. During droughts, this competition becomes particularly intense.

Livestock overgrazing degrades soil quality and changes plant composition, favoring unpalatable species Hirolas cannot eat. Traditional pastoralist communities now manage larger herds than historically possible, intensifying pressure on the land.

Predation Risks

Lions, cheetahs, and wild dogs pose a serious threat to the dwindling Hirola population. In healthy ecosystems, predation maintains balance, but for critically endangered species, each loss is significant.

Fragmented habitats force Hirolas into smaller areas where predators can hunt them more efficiently. Young calves are particularly vulnerable, reducing recruitment rates essential for population recovery.

Lack Of Captive Populations

Unlike many endangered species, Hirolas have no safety net in zoos or breeding facilities anywhere in the world. No captive individuals exist as backup if wild populations collapse.

Previous attempts to establish captive populations failed due to the antelope’s specialized dietary needs and susceptibility to stress. This absence of an insurance population makes field conservation the only option for their survival.

Conservation Efforts

The Ishaqbini Hirola Conservancy represents a ray of hope for these antelopes. This community-run sanctuary protects a predator-free area where Hirolas can breed safely.

Translocated populations in Tsavo East National Park serve as a genetic reservoir. Conservation biologists monitor these groups closely, tracking births, deaths, and movements to guide protection efforts and habitat management strategies.

Community Involvement

Local Somali and Kenyan communities have embraced Hirola conservation, recognizing these antelopes as cultural heritage. Traditional knowledge combined with scientific approaches creates effective protection strategies.

Community rangers patrol for poachers and monitor herds. Schools teach children about Hirola importance. By creating economic incentives tied to conservation, local people become the antelope’s most dedicated guardians.

Global Conservation Significance

The Hirola’s extinction would mark a devastating milestone – the first loss of an entire mammalian genus in mainland Africa since modern record-keeping began. This would represent an irreversible hole in Earth’s biodiversity tapestry.

As indicators of ecosystem health, their decline signals broader environmental degradation affecting countless species. Saving Hirolas means preserving an entire ecological network.