Sharks Freeze When Flipped Over And There’s No Clear Explanation

When you flip a shark upside down, something strange happens – they freeze completely. This bizarre behavior, called tonic immobility, leaves sharks in a trance-like state where they barely move for up to 15 minutes.

Scientists have observed this phenomenon for decades, but surprisingly, we still don’t fully understand why it happens. Let’s explore the mysterious world of shark freezing and the theories behind this peculiar reaction.

Tonic Immobility: The Survival Mechanism Found In Sharks And Other Animals

Sharks aren’t the only creatures that experience this strange freezing response. Many animals like rabbits, lizards, and even some insects display similar behavior when facing danger.

The scientific term “tonic immobility” describes this temporary paralysis that appears almost like hypnosis. For some animals, it’s clearly a defense mechanism – playing dead might make predators lose interest.

But for sharks, top predators themselves, the purpose seems less obvious. This shared trait across different animal groups suggests it might be an ancient response wired into vertebrate brains millions of years ago, persisting even when its original purpose may no longer apply.

The Mystery Behind Sharks’ Freezing Response When Upside Down

Flip a shark belly-up and watch as it transforms from fearsome predator to motionless statue. Marine biologists first documented this behavior in the 1970s, but the exact mechanism remains elusive decades later.

One theory suggests specialized sensory organs called ampullae of Lorenzini might trigger the response. These jelly-filled pores detect electrical fields, and when a shark is inverted, they may receive confusing signals that essentially “short-circuit” the animal’s nervous system.

Another possibility involves the shark’s vestibular system getting disoriented. Without a clear sense of up or down, the brain might initiate a protective shutdown until orientation returns.

Do Sharks Really Enter A Paralysis-Like State When Flipped?

Yes! The phenomenon is absolutely real and well-documented. When turned upside down, most shark species become completely immobile within seconds. Their muscles relax, breathing slows, and they appear almost catatonic.

Remarkably, they remain fully conscious during this state. Their eyes continue tracking movement, and sensors detect their brain remains active. Unlike true sleep, this resembles more of a trance.

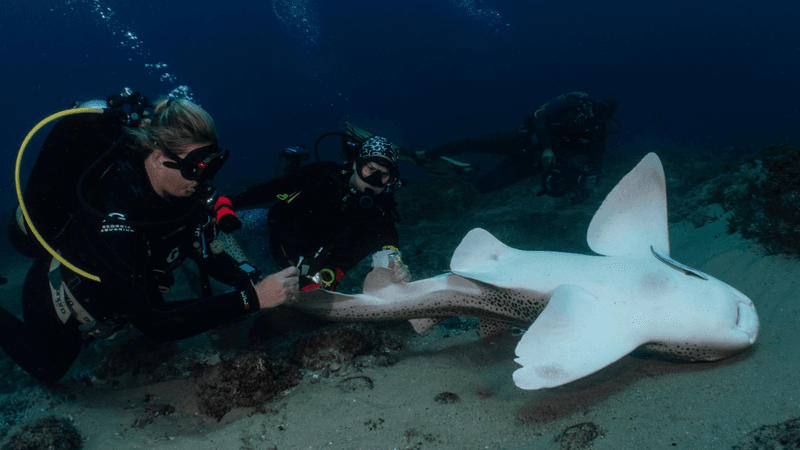

The duration varies by species – nurse sharks might remain frozen for 15 minutes, while great whites recover more quickly. Researchers use this response to safely work with sharks, performing tagging operations or medical procedures without sedatives. The sharks appear completely unharmed when returned to their normal position.

What We Know (And Don’t Know) About Sharks’ Reaction To Being Upside Down

Scientists have confirmed several facts about tonic immobility in sharks. We know it affects nearly all shark species, though some are more susceptible than others. Tiger sharks freeze for shorter periods while nurse sharks might remain immobile for much longer.

We’ve also learned that gentle rubbing of a shark’s snout can induce a similar trance. Certain chemicals in the water may enhance or diminish the response.

The biggest mystery remains the evolutionary purpose. Is it a leftover trait from ancient ancestors? A response to specific predators? Or perhaps related to mating? Despite decades of observation, researchers still debate these fundamental questions, highlighting how much remains unknown about these ancient creatures.

Anti-Predator Strategy: Do Sharks Use “Playing Dead” To Avoid Being Eaten?

Some researchers propose that tonic immobility might have evolved as protection against the sharks’ few natural predators – particularly killer whales. Fascinating footage from 1997 shows orcas deliberately flipping great white sharks to immobilize them before feeding.

The behavior seems counterintuitive. Why would freezing help when being attacked? The answer might lie in predator psychology.

Many predators rely on movement to trigger their feeding response. A completely motionless shark might confuse attackers or reduce their feeding drive. Alternatively, playing dead could make the shark appear sick or unpalatable. For smaller shark species that face more threats, this explanation holds more weight than for apex predators like great whites.

Reproductive Role: Do Male Sharks Invert Females During Mating?

The mating hypothesis offers an intriguing explanation for tonic immobility. Male sharks often bite and hold females during reproduction, sometimes flipping them in the process. A female who freezes might experience less injury during these aggressive encounters.

Researchers have observed that female sharks appear more susceptible to tonic immobility than males in many species. This gender difference supports the mating theory.

The reproductive advantage would explain why this trait persisted through millions of years of evolution. Natural selection would favor females who freeze during mating, as they’d sustain fewer injuries and successfully reproduce more often. However, this doesn’t explain why males also experience the response, suggesting multiple factors might be at play.

Sensory Overload: Do Sharks Use Freezing As A Response To Extreme Stimulation?

The sensory overload theory proposes that tonic immobility serves as an emergency shutdown when sharks receive overwhelming stimuli. Sharks possess incredibly sensitive electroreceptors, pressure detectors, and smell organs that constantly flood their brain with information.

When flipped upside-down, these systems might deliver conflicting signals. The brain, unable to process this chaotic input, initiates a temporary system reset – similar to how computers freeze when overloaded.

Support for this theory comes from observations that sharks enter similar states during electrical stimulation or when their senses are bombarded with intense stimuli. This explanation fits with the brain activity patterns measured during tonic immobility, which show altered but not diminished neural activity.

What Tonic Immobility In Sharks Really Tells Us About Evolutionary Leftovers

Tonic immobility might be an evolutionary vestige – a behavior that once served a crucial purpose but now persists without clear function. Evolution often works this way, preserving traits long after their original purpose disappears.

Ancient shark ancestors faced different predators and environmental challenges than today’s species. The freezing response might have protected these prehistoric creatures from threats that no longer exist.

Similar to how humans have appendixes or wisdom teeth, sharks might carry this behavioral “appendix” in their genetic code. This theory is supported by the observation that tonic immobility appears most pronounced in older, more primitive shark species like nurse sharks, while more recently evolved species show reduced responses.

How Playing Dead Became A Quirk Of The Past For Some Sharks And Rays

Not all sharks respond equally to being flipped. Great whites recover from tonic immobility much faster than nurse sharks. Some highly evolved species barely show the response at all.

This variation suggests we’re witnessing evolution in action. As certain species faced new environmental pressures, those with shorter immobility periods gained survival advantages.

Hammerhead sharks, with their uniquely shaped heads, show particularly weak tonic immobility responses. Their specialized hunting techniques and body shape may have made the freezing response more disadvantageous. Meanwhile, rays – close relatives of sharks – exhibit extremely pronounced tonic immobility, suggesting their evolutionary path favored retaining this ancient trait.

Tonic Immobility Might Not Be A Strategy After All – Just Ancient Muscle Memory

The simplest explanation might be the most accurate: tonic immobility could be a neurological quirk without adaptive purpose. Similar to how humans get dizzy when spinning, sharks might simply experience a neurological hiccup when their orientation changes dramatically.

This non-adaptive hypothesis is gaining support among marine biologists. The brain regions activated during tonic immobility are ancient structures shared across many vertebrates, suggesting the response predates sharks themselves.

Rather than searching for complex evolutionary advantages, we might be observing a fundamental limitation of vertebrate nervous systems. The fact that so many different animals share similar responses supports this view. Sometimes the most fascinating biological mysteries have surprisingly straightforward answers buried in ancient neural circuitry.