Cameras Capture Unexpected Animal Routes Along The U.S.–Mexico Border

Wildlife doesn’t recognize political boundaries. Along the 2,000-mile U.S.–Mexico border, animals have created their own highways, bridges, and tunnels.

Remote cameras set up by researchers have revealed surprising animal behaviors and migration patterns that challenge what we thought we knew about borderland ecology.

These hidden wildlife corridors tell an amazing story of adaptation and survival in one of North America’s most contested landscapes.

Desert Bighorn Sheep’s Surprising Fence Jumps

Desert bighorn sheep have shocked wildlife biologists with their impressive fence-crossing abilities. Camera footage shows these nimble creatures leaping over 6-foot border barriers without breaking stride.

One remarkable ewe was documented leading her entire herd across the same crossing point seasonally for three consecutive years. The sheep time their movements with the desert’s scarce rainfall, following ancient routes to water sources that straddle both countries.

For centuries, these sheep populations were connected, sharing genetic diversity across the landscape. Their persistence in maintaining these cross-border relationships demonstrates how deeply ingrained migration patterns can be in wildlife behavior.

Coati Families Creating Underground Passages

Coatis, those raccoon relatives with long snouts and ringed tails, have engineered their own border solutions. Camera studies reveal multiple family groups collaboratively digging tunnel networks beneath border barriers.

These social creatures maintain specific crossing points used by generation after generation. Researchers documented one remarkable tunnel extending nearly 15 feet, carefully reinforced with packed soil and plant materials.

Coati families from both sides of the border meet at these crossings during specific seasons, exchanging members and maintaining genetic connections. Their determined digging shows how wildlife finds ways around human obstacles, maintaining social structures that depend on cross-border movement.

Ocelot Highway Through Border Gaps

Endangered ocelots utilize a specific set of drainage culverts and natural gaps to move between Texas and Tamaulipas. Camera studies tracked 17 individual cats using just three main crossing points along a 60-mile stretch of border.

These spotted felines time their border crossings carefully, typically moving during moonless nights when human activity is lowest. One female ocelot, tracked for two years, crossed the border 48 times using the exact same drainage culvert.

Without these precise pathways, ocelot populations would become isolated and face genetic problems. Their specialized route selection demonstrates remarkable memory and navigation skills essential for survival in fragmented habitats.

Jaguars Reclaiming Ancient Territories

Male jaguars from Mexico are quietly returning to Arizona and New Mexico after being absent for decades. Camera traps have captured these spotted wanderers using specific mountain passes that offer cover and water sources.

Researchers identified one particular jaguar, nicknamed “El Jefe,” who traveled over 120 miles along a ridge system that crosses the border. The big cats seem to follow ancient pathways used by their ancestors for centuries.

These natural corridors are critical for the species’ recovery in the United States. Without these specific routes, jaguars might never return to their historical range that once extended as far north as the Grand Canyon.

Mountain Lions’ Shared Water Sources

Mountain lions from both countries converge at specific border water sources during drought periods. Camera studies documented 23 different pumas visiting one particular spring that straddles the international boundary.

These big cats established an unwritten timeshare system, with different individuals visiting at specific times to avoid confrontation. A remarkable behavioral adaptation shows males from opposite sides of the border leaving scent markings but rarely engaging in territorial disputes at these crucial water sites.

This water diplomacy reveals sophisticated social arrangements previously unknown in mountain lion behavior. Their ability to negotiate shared resources across international lines demonstrates wildlife’s remarkable capacity for complex social structures when survival depends on cooperation.

Bats Following Ancient Flyways

Millions of Mexican free-tailed bats navigate precise aerial corridors that have remained unchanged for centuries. Special night-vision cameras revealed these mammals following specific mountain passes and river valleys that naturally break up the border landscape.

One colony crosses the border nightly, feeding in the United States before returning to roost caves in Mexico. Researchers discovered these bats can travel over 60 miles during these feeding trips, maintaining flyways used by countless generations.

These aerial highways remain critical for agricultural pest control on both sides of the border. Each bat consumes thousands of insects nightly, providing natural pest management for farmers whose fields span both nations.

Wolves Rediscovering Ancient Territories

Mexican gray wolves are slowly reclaiming historical territories through specific mountain corridors. Camera studies identified three distinct family groups using high-elevation pathways that naturally connect wilderness areas across the border.

These endangered wolves follow game trails that have existed for thousands of years, tracking deer and elk herds that also cross international boundaries. One particular wolf, known as “F1217,” was documented making the 200-mile journey from Mexico to Arizona three times in a single year.

Without these specific mountain passages, wolf recovery would be nearly impossible. Their route selection demonstrates an inherited knowledge of landscape that persists despite decades of absence from these territories.

Pronghorn Antelope’s Seasonal Border Crossings

Pronghorn antelope herds maintain specific seasonal migration routes that cross the border twice yearly. Camera studies revealed entire family groups using the same crossings their ancestors established centuries ago.

These swift animals, North America’s fastest land mammals, have identified gaps in border infrastructure where they can maintain their traditional movements. One remarkable herd of 60 individuals was documented making synchronized crossings during spring and fall migrations.

Their precise timing coincides with seasonal plant growth on opposite sides of the border. This ancient knowledge, passed through generations, shows how deeply migration patterns are embedded in wildlife behavior and how crucial these specific routes are for survival.

Bobcats Using Man-Made Structures

Bobcats have cleverly adapted to use human infrastructure as border crossing points. Camera studies documented these adaptable felines using abandoned buildings, drainage systems, and even railroad bridges to maintain territories that span both countries.

One particularly resourceful female bobcat was recorded using an old ranching tunnel to cross the border 37 times in a single month. These medium-sized cats establish regular patrol routes that incorporate these crossings, timing their movements to avoid human detection.

Their opportunistic use of human structures shows wildlife’s remarkable adaptability. Unlike some species that avoid human elements, bobcats have integrated them into their movement patterns, turning potential barriers into convenient wildlife highways.

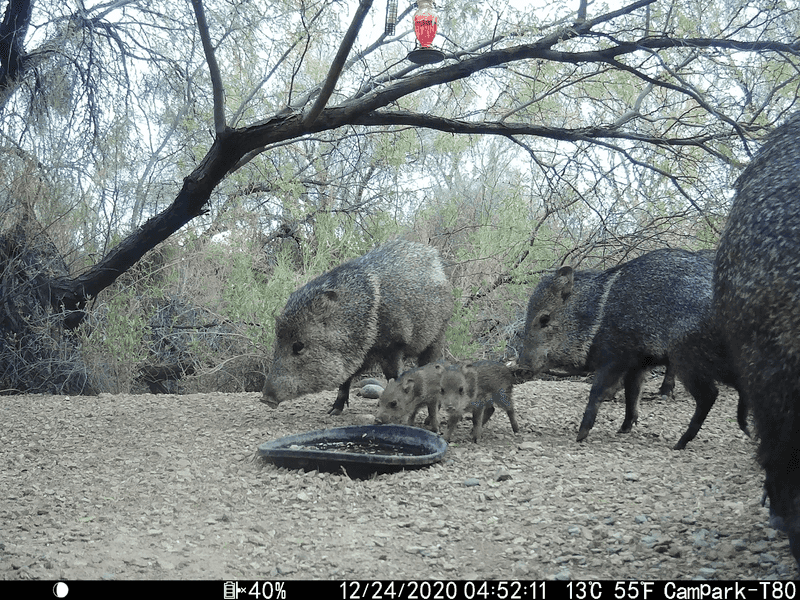

Javelinas Creating Community Pathways

Javelina herds maintain specific border crossing points used by entire communities. Camera studies revealed these pig-like mammals creating well-worn paths through vegetation and around barriers that connect family groups from both countries.

These social creatures hold regular “reunions” where herds from both sides gather at specific border locations. Researchers documented one remarkable gathering where five separate family groups converged at a traditional meeting spot that straddles the international boundary.

These community pathways serve as important social infrastructure, allowing genetic exchange and maintaining cultural knowledge across generations. Their persistent use of specific crossing points demonstrates how deeply social connections influence wildlife movement patterns across political boundaries.