Scientists Release Mosquito Swarms In A Bold Effort To Save Hawaii’s Endangered Birds

Hawaii’s native birds face a deadly crisis – mosquitoes carrying avian malaria are pushing many species toward extinction. With some honeycreepers down to just a few hundred individuals left in the wild, scientists are taking dramatic action.

Rather than trying to kill all mosquitoes, researchers are now releasing millions of lab-modified male mosquitoes in a groundbreaking attempt to save these colorful forest birds before it’s too late.

Hawaii’s Bird Crisis: The Growing Threat Of Avian Malaria

Avian malaria has devastated Hawaii’s native bird populations since mosquitoes arrived in the 1800s. Unlike mainland birds, Hawaiian species evolved in isolation without exposure to this disease, leaving them with zero natural immunity.

Just one bite from an infected mosquito can kill a honeycreeper within days. The disease has already wiped out 17 native bird species, with another 22 teetering on the edge of extinction.

Once abundant across all elevations, surviving native birds now cling to existence only in high mountain forests where cooler temperatures historically limited mosquitoes – but even this final refuge is shrinking as warming temperatures allow mosquitoes to move upward.

How Non-Native Mosquitoes Became A Major Danger For Hawaiian Birds

Mosquitoes were completely absent from Hawaii until the 1800s when European ships accidentally introduced them. The southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus) arrived in water barrels aboard whaling vessels in 1826, forever changing Hawaii’s ecosystem.

These mosquitoes thrived in Hawaii’s warm climate with no natural predators. When avian malaria parasites later arrived with introduced birds, the mosquitoes became deadly carriers.

Native birds had evolved for millions of years without these blood-sucking insects, so they lack defensive behaviors like swatting or avoiding areas with mosquitoes. This makes them especially vulnerable compared to mainland birds that evolved alongside mosquitoes.

Mosquito Swarms Released In Hawaii’s Mountain Forests: Why It’s Happening

Scientists aren’t releasing just any mosquitoes – they’re strategically deploying millions of lab-raised male mosquitoes that have been infected with a bacteria called Wolbachia. Males don’t bite birds or people, so they pose zero disease risk.

The release sites focus on mid-elevation forests where endangered birds and mosquitoes now overlap due to warming temperatures. These areas represent critical battlegrounds for bird survival.

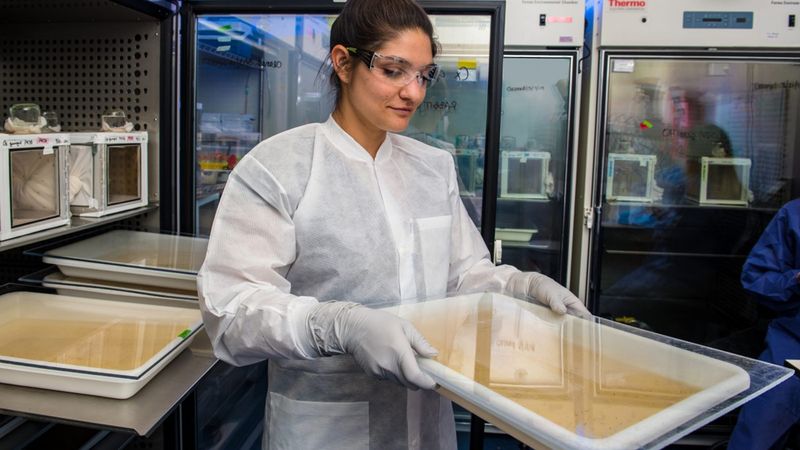

Release methods include both ground teams hiking to remote locations and helicopter drops to reach inaccessible terrain. Each release contains thousands of mosquitoes in biodegradable containers that open automatically, allowing the males to disperse naturally throughout the forest to find wild females.

The Role Of Climate Change In Spreading Mosquitoes Across Hawaii

Rising temperatures have allowed mosquitoes to invade previously safe bird habitats at higher elevations. For every 1°C increase in temperature, mosquitoes can survive about 500 feet higher in the mountains.

Hawaiian honeycreepers once found refuge above 4,000 feet where cool temperatures prevented mosquitoes from reproducing. Climate models predict that by 2100, no Hawaiian forest will be too cold for mosquitoes.

Changing rainfall patterns also create new mosquito breeding grounds. Drought conditions force birds to congregate around remaining water sources – the same places mosquitoes breed. This deadly combination accelerates disease transmission and has made climate change a critical factor in the bird extinction crisis.

The Birth Control Strategy Behind The Mosquito Swarms

The mosquito release program uses a clever reproductive trick rather than pesticides. When Wolbachia-infected males mate with wild females, the resulting eggs never hatch – essentially a form of mosquito birth control.

Female mosquitoes mate only once in their lifetime, so each encounter with a lab-raised male effectively removes that female from the breeding population. This approach targets reproduction rather than trying to kill adult mosquitoes directly.

Scientists estimate that if lab males outnumber wild males by at least 10-to-1, mosquito populations could collapse by over 90% within months. The beauty of this approach is its specificity – it only affects the targeted mosquito species without harming other insects or wildlife.

What Is Wolbachia And How It’s Helping Save Hawaii’s Birds

Wolbachia is a naturally occurring bacteria found in about 60% of insect species worldwide, but not normally in the mosquito species threatening Hawaiian birds. When scientists introduce this bacteria into male mosquitoes, it creates reproductive incompatibility with wild females.

Unlike genetic modification, this method doesn’t change the mosquito’s DNA. Wolbachia simply manipulates the mosquito’s reproductive system from within the cells.

The bacteria has been used successfully to fight human diseases like dengue fever in places like Australia and Brazil. Hawaii’s program adapts this proven technology to save birds instead of people. Scientists consider Wolbachia one of the safest pest management tools because it can’t spread to humans, birds, or other insects.

The Challenges Of Protecting Hawaii’s Endangered Honeycreepers

Hawaiian honeycreepers represent one of the world’s most spectacular examples of adaptive radiation – one ancestral finch species evolved into over 50 different species with unique bills, colors, and feeding habits. Sadly, more than half are already extinct.

The ‘akikiki on Kauai has fewer than 50 birds left in the wild. The ‘akeke’e has fewer than 1,000. Without immediate intervention, these birds could disappear within five years.

Conservation efforts face massive logistical hurdles in Hawaii’s remote terrain. Some critical bird habitat can only be reached by helicopter or multi-day hikes. Breeding programs struggle because many honeycreepers have specialized diets and behaviors that are difficult to replicate in captivity.

Why Traditional Conservation Methods Aren’t Enough In Hawaii

Conventional approaches like habitat protection fail when the threat is airborne. Even pristine forests can’t save birds from mosquito-borne disease.

Captive breeding programs currently house some honeycreepers as insurance populations, but these birds need to return to the wild eventually. Without solving the mosquito problem, releasing captive birds would be sending them to certain death.

Previous attempts at mosquito control using pesticides proved impractical in Hawaii’s rugged landscapes and risked harming the very ecosystems they aimed to protect. Predatory fish released in water sources to eat mosquito larvae damaged native aquatic species. The landscape-scale challenge requires the innovative Wolbachia approach that specifically targets disease-carrying mosquitoes while preserving the rest of Hawaii’s delicate ecosystem.

How Scientists Are Using Male Mosquitoes To Fight Malaria

Male mosquitoes make perfect allies in this conservation battle because they don’t bite or spread disease. They feed exclusively on flower nectar, not blood, making them completely harmless to birds and people.

Laboratories breed millions of male mosquitoes, infect them with Wolbachia, and then sort them from females using automated systems that can process 150,000 mosquitoes per hour. The sorting technology uses size differences – males are smaller – ensuring only males are released.

Field teams monitor effectiveness by setting special traps that collect mosquito eggs from the wild. If the eggs don’t hatch, it proves the lab males are successfully mating with wild females. Initial results show up to 99% reduction in hatching rates in some release areas.

The Coalition Effort: Birds, Not Mosquitoes Leading The Charge

“Birds, Not Mosquitoes” unites over 20 organizations in this unprecedented conservation effort. Federal agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service work alongside state departments, universities, and non-profits including The Nature Conservancy.

Local communities play crucial roles too. Native Hawaiian cultural practitioners advise on project implementation to ensure respect for traditional values and land use practices.

The coalition approach brings diverse expertise – entomologists who understand mosquito biology, veterinarians who monitor bird health, and drone operators who develop delivery systems for remote areas. This collaborative model represents a new approach to conservation where complex problems require multiple perspectives working in harmony rather than isolated efforts.

What’s Next For Hawaii’s Birds: The Future Of Mosquito Population Control

Current releases are just the beginning of a long-term strategy. Scientists plan to establish a self-sustaining population of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes that could permanently suppress disease transmission without repeated releases.

Monitoring will continue for years to track both mosquito populations and bird recovery. Early success indicators would include increased survival rates for juvenile birds and recolonization of lower-elevation forests.

The Hawaii project serves as a global model for other islands facing similar extinction crises. If successful, this approach could help save birds in places like Guam, New Zealand, and the Galapagos. The stakes couldn’t be higher – without intervention, Hawaii could lose most of its remaining native bird species within decades, but this innovative approach offers real hope for the first time in generations.