Megalodon: Scientists Surprised By Largest Shark’s True Diet

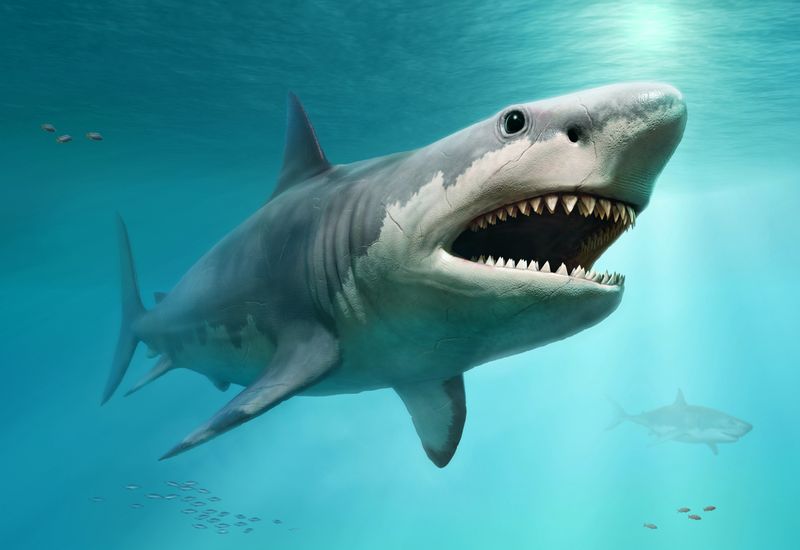

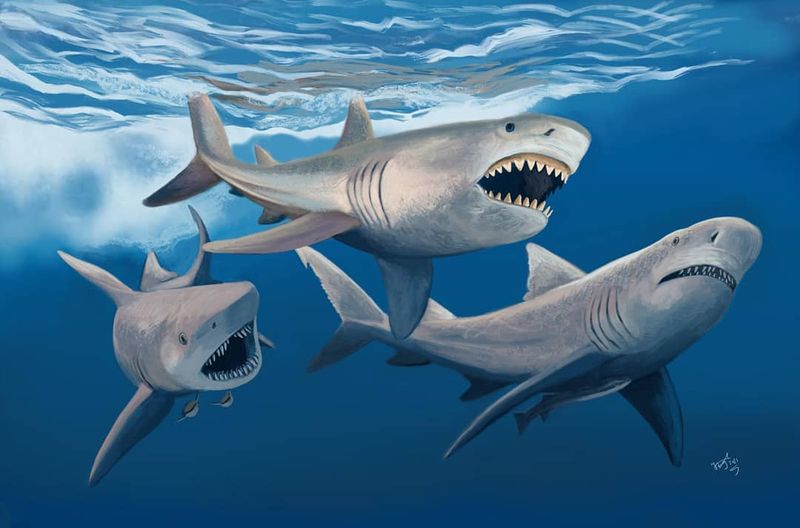

Imagine a shark so massive it could swallow a small boat in one bite! The prehistoric megalodon was the ocean’s ultimate predator, stretching up to 60 feet long with teeth bigger than your hand.

Recent discoveries have completely changed what scientists thought these giants actually ate, turning old theories upside down.

Let’s explore the shocking truth about megalodon’s dining habits that has researchers rethinking everything.

1. Not Just Whale Hunters

Contrary to popular belief, megalodons weren’t exclusively whale hunters. New evidence suggests they had a surprisingly diverse menu that included smaller prey too.

Their jaws could generate enough force to crush a car, yet they often chose medium-sized meals over giant whales. This revelation has scientists reconsidering the entire ecological role of these ancient predators.

2. Tooth-Based Revelations

Teeth tell tales! Recent microscopic analysis of megalodon tooth wear patterns revealed unexpected feeding habits.

The scratches and chips don’t match what scientists would expect from whale-bone contact. Instead, they suggest regular consumption of smaller, bonier fish and medium-sized marine mammals. These dental clues have completely rewritten the megalodon’s dietary biography.

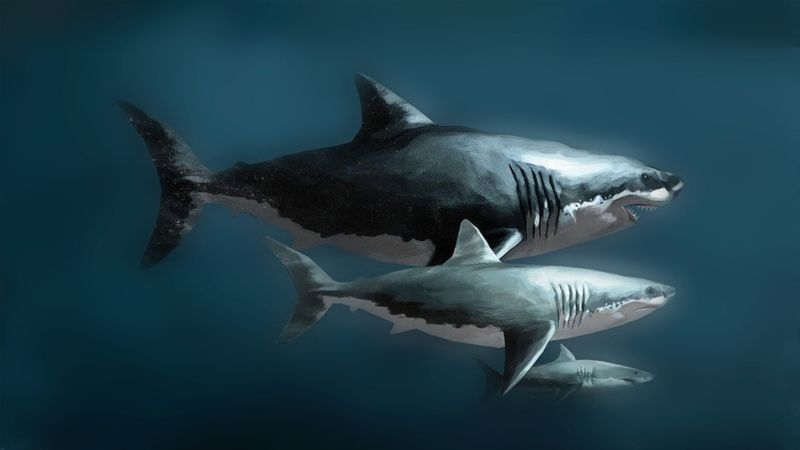

3. Growing Appetite Changes

Baby megalodons started small but mighty! Young sharks apparently preferred smaller fish and gradually worked their way up to bigger meals as they grew.

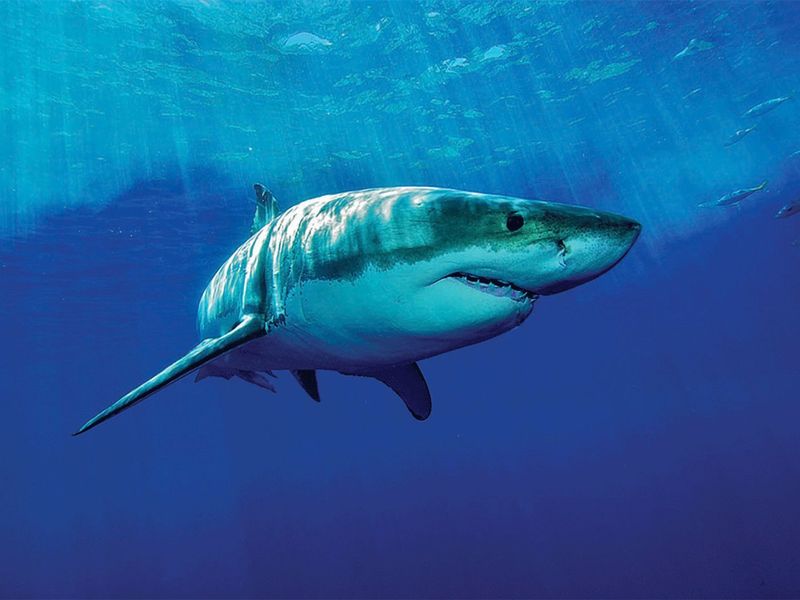

This growth-based diet shift resembles modern great whites but on a gigantic scale. Scientists now believe juvenile megalodons occupied different hunting grounds than adults, creating a complex feeding hierarchy in ancient oceans.

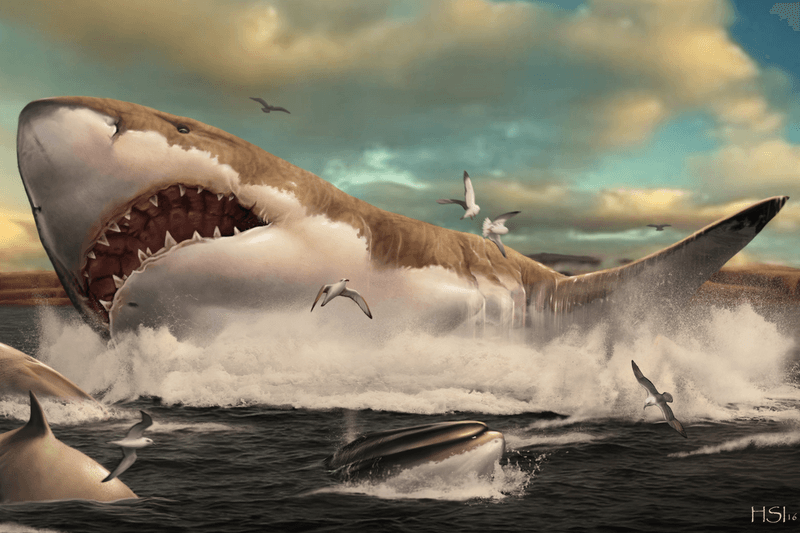

4. Coastal Buffet Preferences

Who needs the deep ocean when coastal waters offer an all-you-can-eat buffet? Fossil evidence suggests megalodons frequently hunted in shallow coastal regions.

These areas provided abundant prey and nursery grounds for their young. Rather than exclusively pursuing giant whales in deep waters, they apparently enjoyed the diverse menu options available along ancient shorelines.

5. Surprising Scavenger Theory

Plot twist: megalodons might have been part-time scavengers! Some researchers now propose these giants occasionally feasted on already-dead marine creatures.

While definitely capable hunters, they likely wouldn’t pass up an easy meal floating by. This opportunistic feeding strategy would have conserved energy and reduced hunting risks, similar to how modern sharks sometimes scavenge.

6. Shellfish Snacking Habits

Crunch time! Emerging evidence suggests megalodons occasionally munched on hard-shelled creatures like giant sea turtles and shellfish.

Their incredible jaw strength made quick work of even the toughest shells. These surprising snacking habits indicate a more versatile predator than previously thought – one that could exploit virtually any protein source in its environment.

7. Competitive Feeding Strategies

Move over, there’s a new theory in town! Recent studies suggest megalodons actively competed with other large predators, forcing them to develop specialized feeding strategies.

Rather than simply overpowering all competition, they likely carved out specific dietary niches. This competitive pressure may explain why their diet was more varied than scientists initially assumed.

8. Chemical Signatures Speak

Ancient chemistry tells modern tales! Cutting-edge isotope analysis of megalodon fossils has revealed chemical signatures that don’t match exclusive whale consumption.

These chemical fingerprints in their remains indicate a diet spanning multiple marine food webs. Scientists were shocked to discover evidence suggesting these giants fed across different trophic levels throughout their lives.

9. Seasonal Dining Patterns

Winter menu different from summer specials? Evidence points to megalodons following seasonal feeding patterns!

They likely tracked migrating prey and adjusted hunting strategies with changing ocean conditions. Just like modern predators change their diets throughout the year, megalodons probably had seasonal favorites based on prey availability and reproductive cycles.

10. Prehistoric Picky Eaters

Taste matters even to giant sharks! Contrary to assumptions that megalodons ate anything they could catch, evidence suggests they were surprisingly selective.

Fossil sites show preferences for certain prey types over others that were equally available. This pickiness might explain why they targeted specific body parts of larger prey, maximizing nutritional value while minimizing hunting effort.

11. Cannibalistic Tendencies Revealed

Family dinner took on a whole new meaning! Shocking evidence suggests megalodons occasionally practiced cannibalism, eating smaller members of their own species.

Bite marks on juvenile megalodon remains tell this disturbing tale. This behavior, while seemingly cruel, is actually common in modern sharks and may have helped regulate population sizes in ancient oceans.

12. Regional Diet Variations

Location, location, location! Megalodons living in different ocean regions apparently developed distinct dietary preferences based on local food availability.

Fossil evidence from various global locations shows regional specialization in hunting techniques and prey selection. Just like regional cuisine varies for humans, megalodon populations likely had their own local specialties.

13. Hunting Method Mysteries

Sneaky giants used strategy, not just size! New bite mark evidence on fossil prey suggests megalodons employed sophisticated hunting techniques rather than simple brute force.

They likely targeted vital areas like flippers to immobilize prey before delivering fatal bites. These tactical approaches required intelligence and adaptation, painting a picture of a methodical hunter rather than mindless chomping machine.

14. Extinction by Starvation Theory

The final meal that never came? Revolutionary thinking suggests megalodons’ specialized diet contributed to their extinction.

As prey species evolved or disappeared during climate changes, these giants couldn’t adapt their feeding strategies quickly enough. Their massive energy requirements became impossible to sustain when preferred food sources dwindled, ultimately spelling doom for the ocean’s greatest predator.