7 Majestic Wild Cat Species In North America (And 4 That Have Recently Vanished From The Region)

North America’s wilderness hides some of the most fascinating feline predators on the planet. From mountain peaks to swampy wetlands, wild cats have adapted to nearly every ecosystem on the continent.

While several magnificent species still roam free across the landscape, others have disappeared in recent decades due to human activity.

1. Mountain Lion: The Silent Shadow

Known by many names – cougar, puma, panther – these tawny predators roam across more North American territory than any other wild cat. Capable of leaping 20 feet horizontally, they silently stalk deer through forests and canyons.

Unlike their roaring big cat cousins, mountain lions communicate through whistles, chirps, and purrs. Their adaptability has allowed them to survive in diverse habitats from Canadian forests to Florida swamps.

2. Bobcat: The Adaptable Hunter

Sporting distinctive ear tufts and a bobbed tail, these medium-sized cats thrive from Mexico to southern Canada. Pound for pound, bobcats are among the fiercest hunters in North America, taking down prey three times their size.

Masters of camouflage, their spotted coats blend perfectly with dappled forest light. Urban development hasn’t stopped these resilient cats – they’ve been spotted in suburban backyards and city parks across the continent.

3. Canada Lynx: The Snowshoe Specialist

With enormous paws that act like natural snowshoes, the Canada lynx glides effortlessly across deep snow that would trap other predators. Its thick silver-gray coat and dramatic facial ruff provide perfect winter camouflage.

A snowshoe hare specialist, the lynx population rises and falls in an intricate dance with its primary prey. Their relationship forms one of nature’s most studied predator-prey cycles. These ghostly cats remain one of the most elusive creatures in North American forests.

4. Ocelot: The Jungle Jewel

With a dazzling spotted coat that once made it a target for fur hunters, the endangered ocelot now clings to existence in the southernmost tip of Texas. These nocturnal hunters have eyes three times more sensitive to light than human eyes.

Twice the size of house cats but smaller than bobcats, ocelots prefer dense thornscrub habitat where they can remain hidden. Each ocelot’s coat pattern is as unique as a human fingerprint, allowing researchers to identify individuals from trail camera photos.

5. Jaguarundi: The Otter Cat

Neither spotted nor striped, the jaguarundi breaks the wild cat mold with its sleek, otter-like appearance. Primarily found in Mexico, small populations venture into Texas and Arizona. Unlike most cats, jaguarundis are often active during daylight hours.

Their unusual elongated bodies and short legs give them a weasel-like appearance as they hunt through dense underbrush. These cats come in two distinct color phases – a rusty-red and a smoky-gray – which were once thought to be separate species.

6. Margay: The Acrobatic Feline

Rarely spotted in the southernmost reaches of Texas, the margay possesses a remarkable adaptation – ankle joints that rotate 180 degrees, allowing it to run headfirst down trees! These small spotted cats spend most of their lives in the treetops.

Margays have been documented mimicking the calls of prey animals – a rare example of hunting by vocal mimicry among cats. Their enormous eyes take up so much space in their skull that they cannot move their eyes, instead turning their entire head to look around.

7. Jaguar: The American King

North America’s largest and most powerful cat once roamed from Argentina to the Grand Canyon. Today, a handful of jaguars still cross from Mexico into Arizona and New Mexico. Their massive jaw strength allows them to pierce turtle shells and crocodile armor.

Unlike other big cats that kill by suffocation, jaguars dispatch prey with a unique skull-piercing bite between the ears. Recent conservation efforts aim to restore corridors for these magnificent cats to reclaim their historic range in the southwestern United States.

8. Eastern Cougar: Ghost Of The Forests

Officially declared extinct in 2018, the eastern cougar once stalked the forests from Maine to South Carolina. The last confirmed individual was killed in Maine in 1938. Despite its disappearance, hundreds of sightings are still reported annually.

Many biologists believe these sightings represent western mountain lions gradually expanding eastward. The eastern cougar’s extinction created a predator vacuum that has contributed to deer overpopulation problems throughout the eastern United States. Their absence continues to affect forest ecosystems decades later.

9. Mexican Grizzly: The Vanished Predator

Once roaming mountains from Arizona to central Mexico, the Mexican grizzly vanished by the 1960s. Smaller and lighter-colored than its northern cousins, this unique subspecies fell victim to systematic extermination campaigns by ranchers and government agencies.

The last confirmed Mexican grizzly was shot in 1960 in Sonora. Despite occasional unconfirmed sightings, biologists consider the subspecies extinct. Their disappearance removed a key predator that helped control deer and javelina populations across the southwestern mountain ecosystems.

10. Florida Panther: The Comeback Cat

Teetering on extinction with fewer than 30 individuals in the 1990s, Florida panthers have clawed their way back to about 200 today. These mountain lion subspecies developed unique adaptations to swamp life, including longer legs for wading and a distinctive crook at the end of their tail.

Genetic rescue through introducing Texas cougars helped reverse inbreeding problems. Still endangered, they face threats from habitat loss and vehicle collisions. Special wildlife underpasses on Florida highways have reduced panther road deaths by over 90% where implemented.

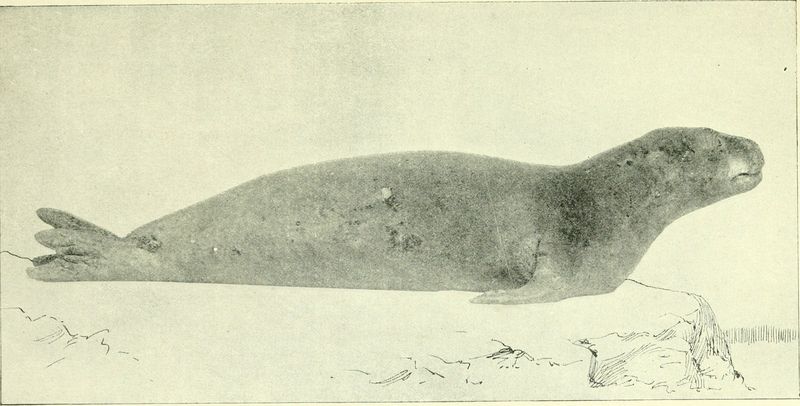

11. Caribbean Monk Seal: The Lost Marine Mammal

The only seal native to the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, this species was declared extinct in 2008. The last confirmed sighting occurred in 1952 at Serranilla Bank between Jamaica and Honduras. Hunting for oil, meat, and blubber drove these gentle creatures to oblivion.

Christopher Columbus recorded killing eight of these “sea wolves” in 1494, beginning centuries of exploitation. Their disappearance marks the only marine mammal extinction in the Americas due to human causes. Scientists believe they played a crucial role in maintaining coral reef ecosystem health.