Devil’s Hole Pupfish Struggling To Survive, Along With Other Endangered Fish Species

Hidden beneath the waters of our planet, a silent crisis unfolds as some of Earth’s most unique fish face extinction.

The Devil’s Hole pupfish – barely an inch long – clings to survival in a single desert cavern in Nevada. This tiny blue fish represents just one of many underwater species on the brink of disappearing forever.

Let’s explore these remarkable creatures and understand why their survival matters to all of us.

1. Devil’s Hole Pupfish: Living On The Edge

Imagine a fish so rare that its entire population lives in a single limestone cavern smaller than your bedroom! The iridescent blue Devil’s Hole pupfish exists nowhere else on Earth except this 93-degree water-filled hole in Nevada’s desert.

Only about 100 individuals remain, making it possibly the world’s rarest fish. Scientists monitor these tiny survivors around the clock, fighting against habitat changes, low oxygen levels, and limited food resources.

Despite being just an inch long, these fish have survived in isolation for thousands of years. Their unique adaptations to extreme conditions fascinate researchers who hope to unlock secrets that might help save other endangered species.

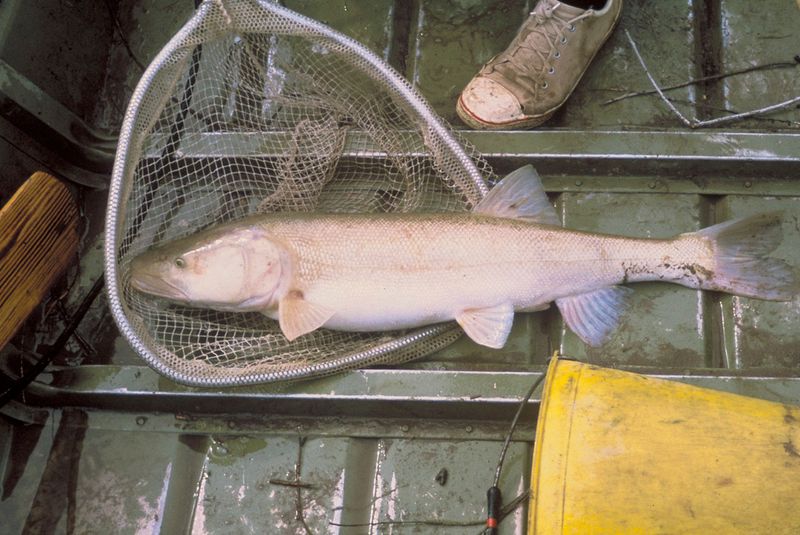

2. Cui-ui: Nevada’s Ancient Survivor

Swimming in Pyramid Lake’s alkaline waters, the cui-ui has witnessed millennia pass by. This large sucker fish grows up to two feet long and can live for an impressive 40 years, making it a true elder of Nevada’s aquatic realm.

For the Northern Paiute tribe, who call themselves “cui-ui ticutta” or “cui-ui eaters,” this fish holds deep cultural significance. Dams and water diversions on the Truckee River have blocked their spawning routes, pushing them toward extinction.

Despite conservation efforts starting in the 1970s, cui-ui remain endangered with only one wild population left. Their unusual adaptation to highly alkaline waters makes them fascinating subjects for scientific study.

3. Colorado Pikeminnow: River Giant In Decline

Once the undisputed king of the Colorado River, this massive predator could reach six feet long and weigh up to 80 pounds! Early settlers called them “white salmon” because of their size and fighting spirit when caught.

Now the Colorado pikeminnow struggles in fragmented rivers. Dams block their epic migrations – these fish once traveled hundreds of miles to spawn, navigating by memory through the complex river system.

Young pikeminnow face additional threats from introduced predatory fish like smallmouth bass. Recovery efforts include creating fish passages around dams and breeding programs, but these river giants remain at just 2% of their historic numbers.

4. Razorback Sucker: Humpbacked Wonder

Named for the distinctive bony ridge on its back, the razorback sucker looks like something from prehistoric times. This bronze-colored fish with its unusual silhouette once thrived throughout the Colorado River Basin.

Razorbacks can live up to 40 years and grow to three feet long. Their specialized mouth allows them to vacuum up algae and small organisms from river bottoms, playing a crucial role in the ecosystem’s health.

Dam construction, water diversion, and non-native fish have devastated their populations. Now, captive breeding programs offer hope, releasing thousands of young razorbacks into protected areas while biologists work to create predator-free zones where these unique fish can recover.

5. Humpback Chub: Canyon Dweller

With its streamlined body and prominent hump, the humpback chub evolved perfectly for life in wild, rushing canyon waters. These remarkable fish navigate the treacherous currents of the Colorado River and its tributaries with impressive skill.

Their unusual body shape – featuring a torpedo-like form with a distinctive hump behind the head – helps them stay stable in swirling waters. Scientists believe their large fins and specialized sensory organs allow them to detect subtle changes in current.

Once abundant in the Grand Canyon region, humpback chub populations crashed after dam construction altered water temperatures and flow patterns. Recent conservation efforts have shown promise, with some populations slowly increasing in protected stretches of river.

6. Totoaba: Mexico’s Endangered Sea Bass

Known as the “cocaine of the sea,” the totoaba faces extinction due to its highly valuable swim bladder. Chinese traditional medicine prizes this organ, driving a black market worth thousands of dollars per pound and fueling illegal fishing operations.

These massive fish – reaching 6 feet and 200 pounds – live only in Mexico’s Gulf of California. They produce booming sounds during spawning season that once filled the waters with underwater choruses.

Gillnets set for totoaba also entangle and kill the critically endangered vaquita porpoise, creating a double conservation crisis. International efforts to stop poaching face challenges from organized crime networks that profit from the illegal trade.

7. Delta Smelt: Tiny Indicator Of Ecosystem Health

Barely the length of your pinky finger, the translucent delta smelt plays an outsized role in California water politics. These tiny fish live only in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, where freshwater and saltwater mix.

As water quality indicators, their declining numbers signal serious problems in California’s water system. Agricultural demands, urban growth, and climate change have altered water flows and quality, pushing these sensitive fish to the brink.

Controversies rage between farmers needing irrigation water and conservationists fighting to maintain minimum water flows for the smelt. Despite captive breeding programs and habitat restoration efforts, wild delta smelt may already be functionally extinct – recent surveys found just a handful of individuals.

8. Shortnose Sturgeon: Living Fossil In Trouble

Armored with bony plates instead of scales, the shortnose sturgeon looks virtually unchanged from its ancestors that swam alongside dinosaurs 70 million years ago. These remarkable “living fossils” can live up to 60 years but reproduce slowly, making population recovery difficult.

Found along the Atlantic coast from Canada to Florida, shortnose sturgeon face threats from dam construction that blocks access to spawning grounds. Their bottom-feeding lifestyle also exposes them to pollutants that accumulate in river sediments.

Female sturgeon don’t reach reproductive age until 15-20 years old and don’t spawn annually. This slow reproduction rate, combined with historic overfishing for their eggs (caviar), created a perfect storm that pushed these ancient fish toward extinction.

9. Pallid Sturgeon: Mississippi’s Pale Giant

Ghostly pale and growing up to six feet long, pallid sturgeon haunt the depths of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers. Their flattened shovel-shaped snouts help them root through river bottoms for food, while sensory barbels – whisker-like projections – detect prey in murky waters.

These prehistoric-looking fish have survived for over 70 million years only to face possible extinction in our lifetime. River channelization has destroyed the sandbars and diverse habitats they need for spawning and feeding.

Scientists track individual fish with surgically implanted transmitters to understand their movements and breeding habits. Despite these efforts, wild reproduction remains extremely rare, with most population maintenance coming from hatchery-released fish.

10. Atlantic Salmon: King Of Fish Dethroned

Once so plentiful they were considered a poor man’s food, wild Atlantic salmon now face extinction throughout much of their native range. These remarkable fish are born in freshwater streams, migrate to the open ocean, then return years later to the exact same streams to spawn.

Their incredible homing ability remains a scientific mystery. Researchers believe they use the Earth’s magnetic field, smell, and even celestial navigation to find their way back to birth streams.

Dam construction, pollution, and overfishing have devastated wild populations. While farmed salmon fill supermarket shelves, wild Atlantic salmon have disappeared from most American rivers. Conservation efforts focus on dam removal and habitat restoration to help these iconic fish recover.

11. Sockeye Salmon: Red Beauties Facing Climate Threats

Famous for turning brilliant red during spawning, sockeye salmon create one of nature’s most spectacular displays when thousands return to mountain lakes. These determined fish swim hundreds of miles upstream, climbing waterfalls and battling currents to reach their spawning grounds.

Climate change now threatens their survival as warming waters create deadly conditions. In 2015, nearly 250,000 sockeye died in the Columbia River when water temperatures rose too high.

Some populations, like Idaho’s Snake River sockeye, have declined to just dozens of returning fish. Tribal communities who have depended on sockeye for thousands of years face cultural losses alongside ecological ones as these iconic fish struggle against human-caused changes to their environment.

12. Winter-run Chinook Salmon: California’s Cold Water Crisis

Sacramento River’s winter-run Chinook salmon face a temperature emergency that threatens their existence. Unlike other salmon that spawn in fall or spring, these specialized fish lay eggs during summer’s heat, requiring cold water to survive.

Shasta Dam’s construction blocked access to their historic spawning grounds in cold mountain streams. Now they depend on releases of cold water from the dam’s reservoir – a resource that becomes scarce during California’s increasingly frequent droughts.

When reservoir levels drop too low, water temperatures rise above the lethal threshold for salmon eggs. In drought years, entire generations have been lost. Emergency measures include capturing wild salmon for hatchery breeding and trucking young fish downstream to avoid lethal river conditions.

13. Rio Grande Silvery Minnow: Tiny Desert Swimmer

Small enough to fit in your palm, the Rio Grande silvery minnow once dominated the mighty Rio Grande River. Now these silver-scaled fish cling to existence in just 5% of their historic range – a 174-mile stretch of river in central New Mexico.

Water diversion for agriculture and cities has left portions of the river completely dry during summer months. These minnows evolved to release floating eggs during spring floods, but dams now prevent the natural flow patterns they depend on for reproduction.

Conservation efforts include collecting and releasing water during critical spawning periods. Scientists also gather eggs during spring runoff, raise them in hatcheries, and release young fish back into the river – a labor-intensive process that keeps this species from disappearing entirely.